05. The American Revolution

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

Paul Revere, “Landing of the Troops,” ca. 1770, via The American Antiquarian Society.

Paul Revere, “Landing of the Troops,” ca. 1770, via The American Antiquarian Society.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 1 *Click here to view the current published draft of this chapter*

I. Introduction

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The American Revolution built a nation on ideals. That nation changed the way the rest of the world thought about governance and set off what historians have come to call “The Age of Revolution.” The right to govern would no longer be the sole right of monarchs and nobility. For contemporary Americans––as heirs of the Revolution––it created the republican institutions that are still with us, and, more importantly, it codified the ideas and propositions that still define us.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 And, yet, the American Revolution was wholly improbable and unpredictable. In 1763, the colonists who inhabited the British Empire’s North American colonies had just helped Britain win a world war. Most colonists had never been more proud to be British. Yet, in little over a decade, those same colonists would declare independence and commit treason against the very same King they previously praised.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 The Revolution’s consequences were equally unpredictable and often paradoxical. A revolution fought in the name of liberty only further secured the status of slavery. Resistance to increased centralized control by a distant government resulted, by 1788, in a more centralized and powerful federal government than called for in the Articles of Confederation. The founders had sought to create a government and society based on the republican ideals of virtue and the public good, in which they would retain power and control. However, their rhetoric unleashed powerful forces that within a few decades would transform the young nation into a democratic state and society, much to the chagrin of the original, elite founders.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

II. The Origins of the American Revolution

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 1 The American Revolution had both long-term origins and short-term causes. In this section, we will look broadly at some of the long-term political, intellectual, cultural, and economic developments in eighteenth century that set the context for the crisis of the 1760s and 1770s.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 1 Britain failed to define the colonies’ relationship to the empire and institute a coherent program of imperial reform. Two factors contributed to these failures. First, Britain was engaged in costly wars from the War of the Spanish Succession at the start of the century through the Seven Years’ War in 1763. Constant war was politically and economically expensive. Second, competing visions of empire divided British officials. Old Whigs and their Tory supporters envisioned an authoritarian empire, based on conquering territory and extracting resources. They sought to eliminate the national debt by raising taxes and cutting spending on the colonies. The radical (or Patriot) Whigs’ based their imperial vision on trade and manufacturing instead of land and resources. They argued that economic growth, not raising taxes, would solve the national debt. Instead of an authoritarian empire, “patriot Whigs” argued that the colonies should have an equal status with that of the mother country. The debate between the two sides raged throughout the eighteenth century, and the lack of consensus prevented coherent reform.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 The colonies developed their own notions of their place in the empire. They saw themselves as British subjects “entitled to all the natural, essential, inherent, and inseparable rights of our fellow subjects in Great-Britain.” Throughout the first half of the eighteenth century, the colonies had experienced significant economic and demographic growth. Their success, they believed, was partly a result of Britain’s hands-off approach to the colonies. That success had made them increasingly important to the economy of the mother country and the empire as a whole. By mid-century, colonists believed that they held a special place in the empire, which justified Britain’s hands-off policy. In 1764, James Otis Jr. wrote, “The colonists are entitled to as ample rights, liberties, and privileges as the subjects of the mother country are, and in some respects to more.”

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 2 In this same period, the colonies developed their own local political institutions. Samuel Adams, in the Boston Gazette, described the colonies as each being a “separate body politic” from Britain. Almost immediately upon each colony’s settlement, they created a colonial assembly. These assemblies assumed many of the same duties as the Commons exercised in Britain, including taxing residents, managing the spending of the colonies’ revenue, and granting salaries to royal officials. In the early 1700s, elite colonial leaders lobbied unsuccessfully to get the Ministry to recognize their assemblies’ legal standing but the Ministry was too occupied with European wars. In the first half of the eighteenth century, royal governors tasked by the Board of Trade made attempts to limit the power of the assemblies, but they were largely unsuccessful. The assemblies’ power only grew. Many colonists came to see the assemblies as having the same jurisdiction over them that Parliament exercised over those in England. They interpreted British inaction as justifying their tradition of local governance. The British Ministry and Parliament, however, saw the issue as deferred until the Ministry chose to directly address the proper role of the assemblies. Conflict was inevitable, but a revolution was not.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Colonial political culture in the colonies also developed differently than that of the mother country. In both Britain and the colonies, land was the key to political participation, but because land was more easily obtained in the colonies, a higher portion of colonists participated in politics. Colonial political culture drew inspiration from the “country” party in Britain. These ideas—generally referred to as the ideology of republicanism—stressed the corrupting nature of power on the individual, the need for those involved in self-governing to be virtuous (i.e., putting the “public good” over their own self-interest) and to be ever vigilant against the rise of conspiracies, centralized control, and tyranny. Only a small fringe in Britain held these ideas, but in the colonies, they were widely accepted.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 2 In the 1740s, two seemingly conflicting bodies of thought—the Enlightenment and the Great Awakening—began to combine in the colonies and challenge older ideas about authority. Perhaps no single philosopher had a greater impact on colonial thinking than John Locke. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke argued that the mind was originally a tabula rasa (or blank slate) and that individuals were formed primarily by their environment. The aristocracy then were wealthy or successful because they had greater access to wealth, education, and patronage and not because they were innately superior. Locke followed this essay with Some Thoughts Concerning Education, which introduced radical new ideas about the importance of education. Education would produce rational human beings capable of thinking for themselves and questioning authority rather than tacitly accepting tradition. These ideas slowly came to have far-reaching effects in the colonies.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 At the same time as Locke’s ideas about knowledge and education spread in North America, the colonies also experienced an unprecedented wave of evangelical Protestant revivalism. In 1739-40, the Rev. George Whitefield, an enigmatic, itinerant preacher, traveled the colonies preaching Calvinist sermons to huge crowds. Unlike the rationalism of Locke, his sermons were designed to appeal to his listeners’ emotions. Whitefield told his listeners that salvation could only be found by taking personal responsibility for one’s own unmediated relationship with God, a process which came to be known as a “conversion” experience. He also argued that the current Church hierarchies populated by “unconverted” ministers only stood as a barrier between the individual and God. In his wake, new itinerant preachers picked up his message and many congregations split. Both Locke and Whitefield had the effect of empowering individuals to question authority and to take their lives into their own hands.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Despite these political and intellectual differences, eighteenth-century colonists were in some ways becoming more culturally similar to Britons, a process often referred to as “Anglicization.” As the colonial economies grew, they quickly became an important market destination for British manufacturing exports. Colonists with disposable income and access to British markets attempted to mimic British culture. By the middle of the eighteenth century, middling-class colonists could also afford items previously thought of as luxuries like British fashions, dining wares, and more. The desire to purchase British goods meshed with the desire to enjoy British liberties.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 These political, intellectual, cultural, and economic developments created fundamental differences between the colonies and the mother country. Together, they combined to create latent tensions that would rise to the surface when, after the Seven Years’ War, Britain finally began to implement a program of imperial reform that conflicted with colonists’ understanding of the empire and their place in it.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

III. The Causes of the American Revolution

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Most immediately, the American Revolution resulted directly from attempts to reform the British Empire after the Seven Years’ War. The Seven Years’ War culminated nearly a half-century of war between Europe’s imperial powers. It was truly a world war, fought between multiple empires on multiple continents. At its conclusion, the British Empire had never been larger. Britain now controlled the North American continent east of the Mississippi River, including French Canada. It had also consolidated its control over India. But, for the ministry, the jubilation was short-lived. The realities and responsibilities of the post-war empire were daunting. War (let alone victory) on such a scale was costly. Britain doubled the national debt to 13.5 times its annual revenue. In addition to the costs incurred in securing victory, Britain was also looking at significant new costs required to secure and defend its far-flung empire, especially western frontiers of the North American colonies. These factors led Britain in the 1760s to attempt to consolidate control over its North American colonies, which, in turn, led to resistance.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 King George III took the crown in 1760 and brought Tories into his Ministry after three decades of Whig rule. They represented an authoritarian vision of empire where colonies would be subordinate. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was Britain’s first postwar imperial action. The King forbade settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains in attempt to limit costly wars with Native Americans. Colonists, however, protested and demanded access to the territory for which they had fought alongside the British.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 In 1764, Parliament passed two more reforms. The Sugar Act sought to combat widespread smuggling of molasses in New England by cutting the duty in half but increasing enforcement. Also, smugglers would be tried by vice-admiralty courts and not juries. Parliament also passed the Currency Act, which restricted colonies from producing paper money. Hard money, like gold and silver coins, was scarce in the colonies. The lack of currency impeded the colonies’ increasingly sophisticated transatlantic economies, but it was especially damaging in 1764 because a postwar recession had already begun. Between the restrictions of the Proclamation of 1763, the Currency Act, and the Sugar Act’s canceling of trials-by-jury for smugglers, some colonists began to see a pattern of restriction and taxation.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 In March 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act. The Sugar Act was an attempt to get merchants to pay an already-existing duty, but the Stamp Act created a new, direct (or internal) tax. Parliament had never before directly taxed the colonists. Instead, colonies contributed to the empire through the payment of indirect, internal taxes, such as customs duties. In 1765, Daniel Dulany of Maryland wrote, “A right to impose an internal tax on the colonies, without their consent for the single purpose of revenue, is denied, a right to regulate their trade without their consent is, admitted.”

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 2 Stamps were to be required on all printed documents, including newspapers, pamphlets, diplomas, legal documents, and even playing cards. Unlike the Sugar Act, which primarily affected merchants, the Stamp Act directly affected numerous groups including printers, lawyers, college graduates, and even sailors who played cards. This led, in part, to broader, more popular resistance.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Resistance took three forms, distinguished largely by class: legislative resistance by elites, economic resistance by merchants, and popular protest by common colonists. Colonial elites responded with legislative resistance initially by passing resolutions in their assemblies. The most famous of the anti-Stamp Act resolutions were the “Virginia Resolves” that declared that the colonists were entitled to “all the liberties, privileges, franchises, and immunities . . . possessed by the people of Great Britain.” When the resolves were printed throughout the colonies, however, they often included three extra, far more radical resolves not passed by the Virginia House of Burgesses, the last of which asserted that only “the general assembly of this colony have any right or power to impose or lay any taxation” and that anyone who argued differently “shall be deemed an enemy to this his majesty’s colony.” The spread of these extra resolves throughout the colonies helped radicalize the subsequent responses of other colonial assemblies and eventually led to the calling of the Stamp Act Congress in New York City in October 1765. Nine colonies sent delegates, including Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, Thomas Hutchinson, Philip Livingston, and James Otis.

¶ 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

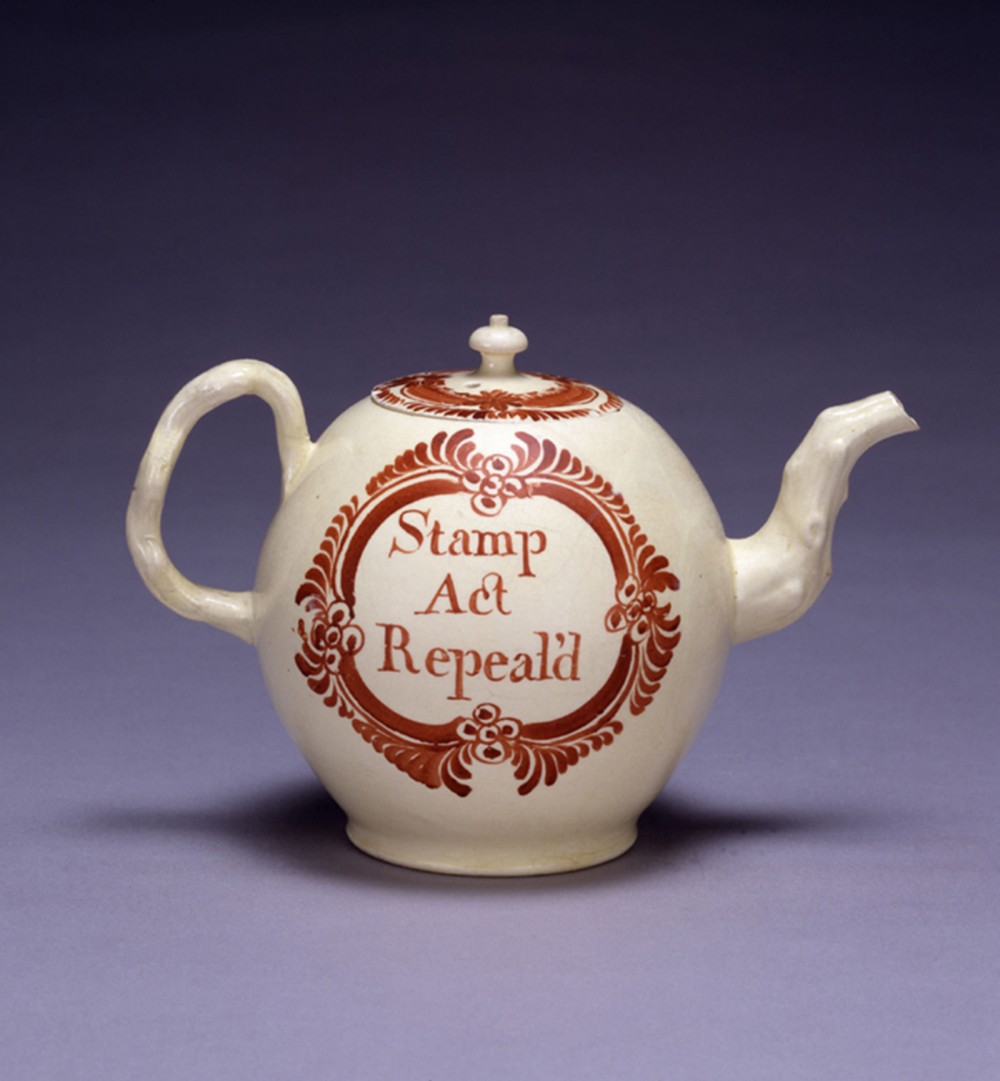

Men and women politicized the domestic sphere by buying and displaying items that conspicuously revealed their position for or against Parliamentary actions. This witty teapot, which celebrates the end of taxation on goods like tea itself, makes clear the owner’s perspective on the egregious taxation. “Teapot, Stamp Act Repeal’d,” 1786, in Peabody Essex Museum. Salem State University, http://teh.salemstate.edu/USandWorld/RoadtoLexington/pages/Teapot_jpg.htm.

Men and women politicized the domestic sphere by buying and displaying items that conspicuously revealed their position for or against Parliamentary actions. This witty teapot, which celebrates the end of taxation on goods like tea itself, makes clear the owner’s perspective on the egregious taxation. “Teapot, Stamp Act Repeal’d,” 1786, in Peabody Essex Museum. Salem State University, http://teh.salemstate.edu/USandWorld/RoadtoLexington/pages/Teapot_jpg.htm.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 The Stamp Act Congress issued a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances,” which, like the Virginia Resolves, declared allegiance to the King and “all due subordination” to Parliament, but also reasserted the idea that colonists were entitled to the same rights as native Britons. Those rights included trial by jury, which had been abridged by the Sugar Act, and the right to only be taxed by their own elected representatives. As Daniel Dulany wrote in 1765, “It is an essential principle of the English constitution, that the subject shall not be taxed without his consent.” Benjamin Franklin called it the “prime Maxim of all free Government.” Because the colonies did not elect members to Parliament, they believed that they were not represented and could not be taxed by that body. In response, Parliament and the Ministry argued that the colonists were “virtually represented,” just like the residents of those boroughs or counties in England that did not elect members to Parliament. However, the colonists rejected the notion of virtual representation, with one pamphleteer calling it a “monstrous idea.”

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 The second type of resistance to the Stamp Act was economic. While the Stamp Act Congress deliberated, merchants in major port cities were preparing non-importation agreements, hoping that their refusal to import British goods would lead British merchants to lobby for the repeal of the Stamp Act. The plan worked. As British exports to the colony dropped considerably, merchants did pressure Parliament to repeal.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 The third, and perhaps, most crucial type of resistance was popular protest. Violent riots broke out in Boston, during which crowds, led by the local Sons of Liberty, burned the appointed stamp collector for Massachusetts, Peter Oliver, in effigy and pulled a building he owned “down to the Ground in five minutes.” Oliver resigned the position of stamp collector the next day. A few days later a crowd also set upon the home of his brother-in-law, Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, who had publicly argued for submission to the stamp tax. Before the evening was over, much of Hutchinson’s home and belongings had been destroyed.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 5 Popular violence and intimidation spread quickly throughout the colonies. In New York City, posted notices read: “PRO PATRIA, The first Man that either distributes or makes use of stampt paper, let him take care of his house, person, and effects. Vox Populi. We dare.” By November 16, all of the original twelve stamp collectors had resigned, and by 1766, Sons of Liberty groups formed in most of the colonies to direct and organize further popular resistance. These tactics had the dual effect of sending a message to Parliament and discouraging colonists from accepting appointments as stamp collectors. With no one to distribute the stamps, the Act became unenforceable.

¶ 28

Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

Violent protest by groups like the Sons of Liberty created quite a stir both in the colonies and in England itself. While extreme acts like the tarring and feathering of Boston’s Commissioner of Customs in 1774 propagated more protest against symbols of Parliament’s tyranny throughout the colonies, violent demonstrations were regarded as acts of terrorism by British officials. This print of the 1774 event was from the British perspective, picturing the Sons as brutal instigators with almost demonic smiles on their faces as they enacted this excruciating punishment on the Custom Commissioner. Philip Dawe (attributed), “The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering,” Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Philip_Dawe_%28attributed%29,_The_Bostonians_Paying_the_Excise-man,_or_Tarring_and_Feathering_%281774%29.jpg.

Violent protest by groups like the Sons of Liberty created quite a stir both in the colonies and in England itself. While extreme acts like the tarring and feathering of Boston’s Commissioner of Customs in 1774 propagated more protest against symbols of Parliament’s tyranny throughout the colonies, violent demonstrations were regarded as acts of terrorism by British officials. This print of the 1774 event was from the British perspective, picturing the Sons as brutal instigators with almost demonic smiles on their faces as they enacted this excruciating punishment on the Custom Commissioner. Philip Dawe (attributed), “The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering,” Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Philip_Dawe_%28attributed%29,_The_Bostonians_Paying_the_Excise-man,_or_Tarring_and_Feathering_%281774%29.jpg.

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 Pressure on Parliament grew until, in March of 1766, they repealed the Stamp Act. But to save face and to try to avoid this kind of problem in the future, Parliament also passed the Declaratory Act, asserting that Parliament had the “full power and authority to make laws . . . to bind the colonies and people of America . . . in all cases whatsoever.” However, colonists were too busy celebrating the repeal of the Stamp Act to take much notice of the Declaratory Act. In New York City, the inhabitants raised a huge lead statue of King George III in honor of the Stamp Act’s repeal. It could be argued that there was no moment at which colonists felt more proud to be members of the free British Empire than 1766. But Britain still needed revenue from the colonies.

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 The colonies had resisted the implementation of direct taxes, but the Declaratory Act reserved Parliament’s right to impose them. And, in the colonists’ dispatches to Parliament and in numerous pamphlets, they had explicitly acknowledged the right of Parliament to regulate colonial trade. So Britain’s next attempt to draw revenues from the colonies, the Townshend Acts, were passed in June 1767, creating new customs duties on common items, like lead, glass, paint, and tea, instead of direct taxes. The Acts also created and strengthened formal mechanisms to enforce compliance, including a new American Board of Customs Commissioners and more vice-admiralty courts to try smugglers. Revenues from customs seizures would be used to pay customs officers and other royal officials, including the governors, thereby incentivizing them to convict offenders. These acts increased the presence of the British government in the colonies and circumscribed the authority of the colonial assemblies, since paying the governor’s salary gave the assemblies significant power over them. Unsurprisingly, colonists, once again, resisted.

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 Even though these were duties, many colonial resistance authors still referred to them as “taxes,” because they were designed primarily to extract revenues from the colonies not to regulate trade. John Dickinson, in his “Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer,” wrote, “That we may legally be bound to pay any general duties on these commodities, relative to the regulation of trade, is granted; but we being obliged by her laws to take them from Great Britain, any special duties imposed on their exportation to us only, with intention to raise a revenue from us only, are as much taxes upon us, as those imposed by the Stamp Act.” Hence, many authors asked: once the colonists assented to a tax in any form, what would stop the British from imposing ever more and greater taxes on the colonists?

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 New forms of resistance emerged in which elite, middling, and working class colonists participated together. Merchants re-instituted non-importation agreements, and common colonists agreed not to consume these same products. Lists were circulated with signatories promising not to buy any British goods. These lists were often published in newspapers, bestowing recognition on those who had signed and led to pressure on those who had not.

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 Women, too, became involved to an unprecedented degree in resistance to the Townshend Acts. They circulated subscription lists and gathered signatures. The first political newspaper essays written by women appeared. Also, without new imports of British clothes, colonists took to wearing simple, homespun clothing. Spinning clubs were formed, in which local women would gather at one their homes and spin cloth for homespun clothing for their families and even for the community.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 Homespun clothing quickly became a marker of one’s virtue and patriotism, and women were an important part of this cultural shift. At the same time, British goods and luxuries previously desired now became symbols of tyranny. Non-importation, and especially, non-consumption agreements changed colonists’ cultural relationship with the mother country. Committees of inspection that monitored merchants and residents to make sure that no one broke the agreements. Offenders could expect to have their names and offenses shamed in the newspaper and in broadsides.

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 Non-importation and non-consumption helped forge colonial unity. Colonies formed Committees of Correspondence to update the progress of resistance in each colony. Newspapers reprinted exploits of resistance, giving colonists a sense that they were part of a broader political community. The best example of this new “continental conversation” came in the wake of the “Boston Massacre.” Britain sent regiments to Boston in 1768 to help enforce the new acts and quell the resistance. On the evening of March 5, 1770, a crowd gathered outside the Custom House and began hurling insults, snowballs, and perhaps more at the young sentry. When a small number of soldiers came to the sentry’s aid, the crowd grew increasingly hostile until the soldiers fired. After the smoke cleared, five Bostonians were dead, including Crispus Attucks, a former slave turned free dockworker. The soldiers were tried in Boston and won acquittal, thanks, in part, to their defense attorney, John Adams. News of the “Boston Massacre” spread quickly through the new resistance communication networks, aided by a famous engraving attributed to Paul Revere, which depicted bloodthirsty British soldiers with grins on their faces firing into a peaceful crowd. The engraving was quickly circulated and reprinted throughout the colonies, generating sympathy for Boston and anger with Britain.

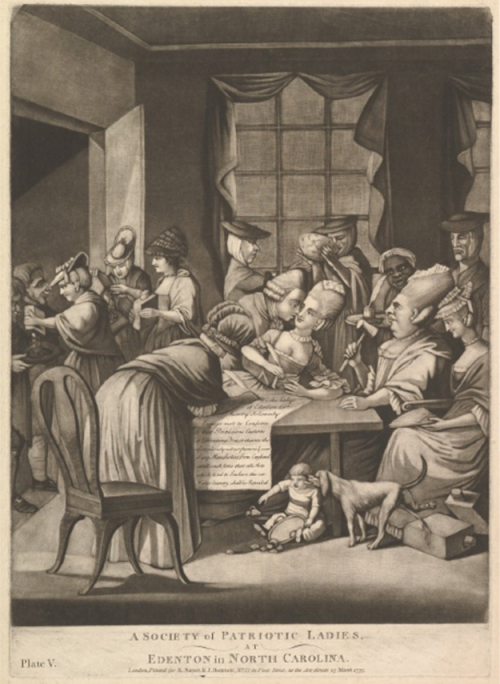

¶ 36

Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

This iconic image of the Boston Massacre by Paul Revere sparked fury in both Americans and the British by portraying the redcoats as brutal slaughterers and the onlookers as helpless victims. The events of March 5, 1770 did not actually play out as Revere pictured them, yet his intention was not simply to recount the affair. Revere created an effective propaganda piece that lent credence to those demanding that the British authoritarian rule be stopped. Paul Revere (engraver), “The bloody massacre perpetrated in King Street Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regt.,” 1770. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661777/.

This iconic image of the Boston Massacre by Paul Revere sparked fury in both Americans and the British by portraying the redcoats as brutal slaughterers and the onlookers as helpless victims. The events of March 5, 1770 did not actually play out as Revere pictured them, yet his intention was not simply to recount the affair. Revere created an effective propaganda piece that lent credence to those demanding that the British authoritarian rule be stopped. Paul Revere (engraver), “The bloody massacre perpetrated in King Street Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regt.,” 1770. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661777/.

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 Resistance again led to repeal. In March of 1770, Parliament repealed all of the new duties except the one on tea, which, like the Declaratory Act, was left to save face and assert that Parliament still retained the right to tax the colonies. The character of colonial resistance had changed between 1765 and 1770. During the Stamp Act resistance, elites wrote resolves and held congresses while violent, popular mobs burned effigies and tore down houses, with minimal coordination between colonies. But methods of resistance against the Townshend Acts became more inclusive and more coordinated. Colonists previously excluded from meaningful political participation now gathered signatures, and colonists of all ranks participated in the resistance by not buying British goods.

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 Britain’s failed attempts at imperial reform in the 1760s created an increasingly vigilant and resistant colonial population and, most importantly, an enlarged political sphere––both on the colonial and continental levels––far beyond anything anyone could have imagined a few years earlier. A new sense of shared grievances began to join the colonists in a shared American political identity.

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0

IV. Independence

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 1 Following the Boston Massacre in 1770, the conflict between the colonies and the mother country cooled. The colonial economy improved as the postwar recession receded. The Sons of Liberty in some colonies sought to continue nonimportation even after the repeal of the Townshend Acts. But, in New York, a door-to-door poll of the population revealed that the majority wanted to end nonimportation. And so April 1770 to the spring of 1773 passed largely without incident. But Britain’s desire and need to reform imperial administration remained.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act to aid the failing East India Company, which had fallen behind in the annual payments it owed Britain. But the Company was not only drowning in debt; it was also drowning in tea, with almost 15 million pounds of it in stored in warehouses from India to England. So, in 1773, the Parliament passed the Regulating Act, which effectively put the troubled company under government control. It then passed the Tea Act, which would allow the Company to sell its tea in the colonies directly and without the usual import duties. This would greatly lower the cost of tea for colonists, but, again, they resisted.

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 Merchants resisted because they deplored the East India Company’s monopoly status that made it harder for them to compete. But, like the Sugar Act, it only affected a small, specific group of people. The widespread support for resisting the Tea Act had more to do with principles. By buying the tea, even though it was cheaper, colonists would be paying the duty and thereby implicitly acknowledging Parliament’s right to tax them. According to the Massachusetts Gazette, Prime Minister Lord North was a “great schemer” who sought “to out wit us, and to effectually establish that Act, which will forever after be pleaded as a precedent for every imposition the Parliament of Great-Britain shall think proper to saddle us with.”

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 The Tea Act stipulated that the duty had to be paid when the ship unloaded. Newspaper essays and letters throughout the summer of 1773 in the major port cities debated what to do upon the ships’ arrival. In November, the Boston Sons of Liberty, led by Samuel Adams and John Hancock, resolved to “prevent the landing and sale of the [tea], and the payment of any duty thereon” and to do so “at the risk of their lives and property.” The meeting appointed men to guard the wharfs and make sure the tea remained on the ships until they returned to London. This worked and the tea did not reach the shore, but by December 16, the ships were still there. Hence, another town meeting was held at the Old South Meeting House, at the end of which dozens of men disguised as Mohawk Indians made their way to the wharf. The Boston Gazette reported what happened next:

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 But, behold what followed! A number of brave & resolute men, determined to do all in their power to save their country from the ruin which their enemies had plotted, in less than four hours, emptied every chest of tea on board the three ships . . . amounting to 342 chests, into the sea ! ! without the least damage done to the ships or any other property.

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 As word spread throughout the colonies, patriots were emboldened to do the same to the tea sitting in their harbors. Tea was destroyed in Charleston, Philadelphia, and New York, with numerous other smaller “tea parties” taking place throughout 1774.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 Britain’s response was swift. The following spring, Parliament passed four acts known collectively, by the British, as the “Coercive Acts.” Colonists, however, referred to them as the “Intolerable Acts.” First, the Boston Port Act shut down the harbor and cut off all trade to and from the city. The Massachusetts Government Act put the colonial government entirely under British control, dissolving the assembly and restricting town meetings. The Administration of Justice Act allowed any royal official accused of a crime to be tried in Britain rather than by Massachusetts courts and juries. Finally, the Quartering Act, passed for all colonies, allowed the British army to quarter newly arrived soldiers in colonists’ homes. Boston had been deemed in open rebellion, and the King, his Ministry, and Parliament acted decisively to end the rebellion.

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 2 The other colonies came to the aid of Massachusetts. Colonists collected food to send to Boston. Virginia’s House of Burgesses called for a day of prayer and fasting to show their support. In Massachusetts, patriots created the “Provincial Congress,” and, throughout 1774, they seized control of local and county governments and courts. In New York, citizens elected committees to direct the colonies’ response to the Coercive Acts, including a Mechanics’ Committee of middling colonists. By early 1774, Committees of Correspondence and/or extra-legal assemblies were established in all of the colonies except Georgia. And throughout the year, they followed Massachusetts’ example by seizing the powers of the royal governments.

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 2 Popular protest spread across the continent and down through all levels of colonial society. The ladies of Edenton, North Carolina, for example, signed an agreement to “follow the laudable example of their husbands” in avoiding boycotted items from Britain. The ladies of Edenton were not alone in their desire to support the war effort by what means they could. Women across the thirteen colonies could most readily express their political sentiments as consumer and producers. Because women were often making decisions regarding which household items to purchase, their participation in consumer boycotts held particular weight. Some women also took to the streets as part of more unruly mob actions, participating in grain riots, raids on the offices of royal officials, and demonstrations against the impressment of men into naval service. The agitation of so many empowered an emboldened response from elites.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 Committees of Correspondence agreed to send delegates to a Continental Congress to coordinate an inter-colonial response. The First Continental Congress convened on September 5, 1774. Over the next six weeks, elite delegates from every colony but Georgia issued a number of documents including a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances.” This document repeated the arguments that colonists had been making since 1765: colonists retained all the rights of native Britons, including the right to be taxed only by their own elected representatives as well as the right to trials-by-juries.

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 Most importantly, the Congress issued a document known as the “Continental Association.” The Association declared that “the present unhappy situation of our affairs is occasioned by a ruinous system of colony administration adopted by the British Ministry about the year 1763, evidently calculated for enslaving these Colonies, and, with them, the British Empire.” The Association recommended “that a committee be chosen in every county, city, and town … whose business it shall be attentively to observe the conduct of all persons touching this association.” These Committees of Inspection would consist largely of common colonists. They were effectively deputized to police their communities and instructed to publish the names of anyone who violated the Association so they “may be publicly known, and universally condemned as the enemies of American liberty.” The delegates also agreed to a continental non-importation, non-consumption, and non-exportation agreement and to “wholly discontinue the slave trade.” In all, the Continental Association was perhaps the most radical document of the period. It sought to unite and direct twelve revolutionary governments, establish economic and moral policies, and empower common colonists by giving them an important and unprecedented degree of on-the-ground political power.

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 But not all colonists were patriots; indeed, many remained faithful to the King and Parliament, while a good number took a neutral stance. As the situation intensified throughout 1774 and early 1775, factions emerged within the resistance movements in many colonies. Elite merchants who traded primarily with Britain, Anglican clergy, and colonists holding royal offices depended on and received privileges from their relationship with Britain. Initially, they sought to exert a moderating influence on the resistance committees but, following the Association, many colonists began to worry that the resistance was too radical and aimed at independence. They, like most colonists in this period, still expected a peaceful conciliation with Britain.

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 However, by the time the Continental Congress met again in May 1775, war had already broken out in Massachusetts. On April 19, 1775, British regiments set out to seize local militias’ arms and powder stores in Lexington and Concord. The town militia met them at the Lexington Green. The British ordered the militia to disperse when someone fired, setting off a volley from the British. The battle continued all the way to the next town, Concord. News of the events at Lexington spread rapidly throughout the countryside. Militia members, known as “minutemen,” responded quickly and inflicted significant casualties on the British regiments as they chased them back to Boston. Approximately 20,000 colonial militiamen lay siege to Boston, effectively trapping the British. In June, the militia set up fortifications on Breed’s Hill overlooking the city. In the misnamed “Battle of Bunker Hill,” the British attempted to dislodge them from the position with a frontal assault, and, despite eventually taking the hill, they suffered severe casualties at the hands of the colonists.

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 While men in Boston fought and died, the Continental Congress struggled to organize a response. The radical Massachusetts delegates––including John Adams, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock––implored the Congress to support the Massachusetts militia then laying siege to Boston with little to no supplies. Meanwhile, many delegates from the Middle Colonies––including New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia––took a more moderate position, calling for renewed attempts at reconciliation. In the South, the Virginia delegation contained radicals such as Richard Henry Lee and Thomas Jefferson, while South Carolina’s delegation included moderates like John and Edward Rutledge. The moderates worried that supporting the Massachusetts militia would be akin to declaring war.

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 The Congress struck a compromise, agreeing to adopt the Massachusetts militia and form a Continental Army, naming Virginia delegate, George Washington, commander-in-chief. They also issued a “Declaration of the Causes of Necessity of Taking Up Arms” to justify this decision. At the same time, the moderates drafted an “Olive Branch Petition” which assured the King that the colonists “most ardently desire[d] the former Harmony between [the mother country] and these Colonies.” Many understood that the opportunities for reconciliation were running out. After Congress had approved the document, Benjamin Franklin wrote to a friend saying, “The Congress will send one more Petition to the King which I suppose will be treated as the former was, and therefore will probably be the last.” Congress was in the strange position of attempting reconciliation while publicly raising an army.

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 The petition arrived in England on August 13, 1775, but, before it was delivered, the King issued his own “Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition.” He believed his subjects in North America were being “misled by dangerous and ill-designing men,” who, were “traitorously preparing, ordering, and levying war against us.” In an October speech to Parliament, he dismissed the colonists’ petition. The King had no doubt that the resistance was “manifestly carried on for the purpose of establishing an independent empire.” By the start of 1776, talk of independence was growing while the prospect of reconciliation dimmed.

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 In the opening months of 1776, independence, for the first time, became part of the popular debate. Town meetings throughout the colonies approved resolutions in support of independence. Yet, with moderates still hanging on, it would take another seven months before the Continental Congress officially passed the independence resolution. A small forty-six-page pamphlet published in Philadelphia and written by a recent immigrant from England captured the American conversation. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense argued for independence by denouncing monarchy and challenging the logic behind the British Empire, saying, “There is something absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island.” His combination of easy language, biblical references, and fiery rhetoric proved potent and the pamphlet was quickly published throughout the colonies. Arguments over political philosophy and rumors of battlefield developments filled taverns throughout the colonies.

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 George Washington had taken control of the army and after laying siege to Boston forced the British to retreat to Halifax. In Virginia, the royal governor, Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation declaring martial law and offering freedom to “all indentured servants, Negros, and others” if they would leave their masters and join the British.

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 Though only about 500-1000 slaves joined Lord Dunmore’s “Ethiopian regiment,” thousands more flocked to the British later in the war, risking capture and punishment for a chance at freedom. Former slaves occasionally fought, but primarily served as laborers, skilled workers, and spies, in companies called “Black Pioneers.” British motives for offering freedom were practical rather than humanitarian, but the proclamation was the first mass emancipation of enslaved people in American history. Slaves could now choose to run and risk their lives for possible freedom with the British army, or hope that the United States would live up to its ideals of liberty.

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0 Dunmore’s Proclamation had the additional effect of pushing many white Southerners into rebellion. After the Somerset case in 1772 ruled that slavery would not be allowed on the British mainland, some American slave-owners began to worry about the growing abolitionist movement in the mother country. Somerset and now Dunmore began to convince some slave owners that a new independent nation might offer a surer protection for slavery. Indeed, the Proclamation laid the groundwork for the very unrest that loyal southerners had hoped to avoid. Consequently, slaveholders often used violence to prevent their slaves from joining the British or rising against them. Virginia enacted regulations to prevent slave defection, threatening to ship rebellious slaves to the West Indies or execute them. Many masters transported their enslaved people inland, away from the coastal temptation to join the British armies, sometimes separating families in the process.

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0 On May 10, 1776, nearly two months before the Declaration of Independence, the Congress voted a resolution calling on all colonies that had not already established revolutionary governments to do so and to wrest control from royal officials. The Congress also recommended that the colonies should begin preparing new written constitutions. In many ways, this was the Congress’s first declaration of independence. A few weeks later, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee offered the following resolution:

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0 Delegates went scurrying back to their assemblies for new instructions and nearly a month later, on July 2, the resolution finally came to a vote. It was passed 12-0 with New York abstaining.

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 Between the proposal and vote, a committee had been named to draft a declaration in case the resolution passed. Virginian Thomas Jefferson drafted the document, with edits being made by his fellow committee members John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, and then again by the Congress as a whole. The famous preamble went beyond the arguments about the rights of British subjects under the British Constitution, instead referring to “natural law”:

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0 We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0 The majority of the document outlined a list of specific grievances that the colonists had with the many actions taken by the British during the 1760s and 1770s to reform imperial administration. An early draft blamed the British for the transatlantic slave trade and even for discouraging attempts by the colonists to promote abolition. Delegates from South Carolina and Georgia as well as those from northern states who profited from the trade all opposed this language and it was removed.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0 Neither the grievances nor the rhetoric of the preamble were new. Instead, they were the culmination of both a decade of popular resistance to imperial reform and decades more of long-term developments that saw both sides develop incompatible understandings of the British Empire and the colonies’ place within it. The Congress approved the document on July 4, 1776. However, it was one thing to declare independence; it was quite another to win it on the battlefield.

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0

V. The War for Independence

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0 The war began at Lexington and Concord, more than a year before Congress declared independence. In 1775, the British believed that the mere threat of war and a few minor incursions to seize supplies would be enough to cow the colonial rebellion. Those minor incursions, however, turned into a full-out military conflict. Despite an early American victory in Boston, the new nation faced the daunting task of taking on the world’s largest military.

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0 In the summer of 1776, the forces that had been at Boston arrived at New York. The largest expeditionary force in British history, including tens of thousands of German mercenaries known as “Hessians” followed soon after. New York was the perfect location to launch expeditions aimed at seizing control of the Hudson River and isolate New England from the rest of the continent. Also, New York contained many loyalists, particularly among the merchant and Anglican communities. In October, the British finally launched an attack on Brooklyn and Manhattan. The Continental Army took severe losses before retreating through New Jersey. With the onset of winter, Washington needed something to lift morale and encourage reenlistment. Therefore, he launched a successful surprise attack on the Hessian camp at Trenton on Christmas Day, by ferrying the few thousand men he had left across the Delaware River under the cover of night. The victory won the Continental Army much needed supplies and a morale boost following the disaster at New York.

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0 An even greater success followed in upstate New York. In 1777, in an effort to secure the Hudson River, British General John Burgoyne led an army from Canada through upstate New York. There, he was to meet up with a detachment of General Howe’s forces marching north from Manhattan. However, Howe abandoned the plan without telling Burgoyne and instead sailed to Philadelphia to capture the new nation’s capital. The Continental Army defeated Burgoyne’s men at Saratoga, New York. This victory proved a major turning point in the war. Benjamin Franklin had been in Paris trying to secure a treaty of alliance with the French. However, the French were reluctant to back what seemed like an unlikely cause. News of the victory at Saratoga convinced the French that the cause might not have been as unlikely as they had thought. A “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” was signed on February 6, 1778. The treaty effectively turned a colonial rebellion into a global war as fighting between the British and French soon broke out in Europe and India.

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0 Howe had taken Philadelphia in 1777 but returned to New York once winter ended. He slowly realized that European military tactics would not work in North America. In Europe, armies fought head-on battles in attempt to seize major cities. However, in 1777, the British had held Philadelphia and New York and yet still weakened their position. Meanwhile, Washington realized after New York that the largely untrained Continental Army could not match up in head-on battles with the professional British army. So he developed his own logic of warfare, which involved smaller, more frequent skirmishes and avoided any major engagements that would risk his entire army. As long as he kept the army intact, the war would continue, no matter how many cities the British captured.

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0 In 1778, the British shifted their attentions to the South, where they believed they enjoyed more popular support. Campaigns from Virginia to Georgia captured major cities but the British simply did not have the manpower to retain military control. And, upon their departures, severe fighting ensued between local patriots and loyalists, often pitting family members against one another. The War in the South was truly a civil war.

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 By 1781, the British were also fighting France, Spain, and Holland. The British public’s support for the costly war in North America was quickly waning. The Americans took advantage of the British southern strategy with significant aid from the French army and navy. In October, Washington marched his troops from New York to Virginia in an effort to trap the British southern army under the command of Gen. Charles Cornwallis. Cornwallis had dug his men in at Yorktown awaiting supplies and reinforcements from New York. However, the Continental and French armies arrived first, quickly followed by a French navy contingent, encircling Cornwallis’s forces and, after laying siege to the city, forcing his surrender. The capture of another army left the British without a new strategy and without public support to continue the war. Peace negotiations took place in France and the war came to an official end on September 3, 1783.

¶ 74

Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0

Lord Cornwallis’s surrender signalled the victory of the American revolutionaries over what they considered to be the despotic rule of Britain. This moment would live on in American memory as a pivotal one in the nation’s origin story, prompting the United States government to commission artist John Trumbull to create this painting of the event in 1817. John Trumbull, Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, 1820. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Surrender_of_Lord_Cornwallis.jpg.

Lord Cornwallis’s surrender signalled the victory of the American revolutionaries over what they considered to be the despotic rule of Britain. This moment would live on in American memory as a pivotal one in the nation’s origin story, prompting the United States government to commission artist John Trumbull to create this painting of the event in 1817. John Trumbull, Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, 1820. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Surrender_of_Lord_Cornwallis.jpg.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0 Americans celebrated their victory, but it came at great cost. Soldiers suffered through brutal winters with inadequate resources. During the single winter at Valley Forge, over 2,500 Americans died from disease and exposure. Life was not easy on the home front either. Women on both sides of the conflict were frequently left alone to care for their households. In addition to their existing duties, women took on roles usually assigned to men on farms and in shops and taverns. Abigail Adams addressed the difficulties she encountered while “minding family affairs” on their farm in Braintree, Massachusetts. Abigail managed the planting and harvesting of crops, in the midst of severe labor shortages and inflation, while dealing with several tenants on the Adams’ property, raising her children, and making clothing and other household goods. In order to support the family economically during John’s frequent absences and the uncertainties of war, Abigail also invested in several speculative schemes and sold imported goods.

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 While Abigail remained safely out of the fray, other women were not so fortunate. The Revolution was, in essence, a civil war; fought on women’s very doorsteps, in the fields next to their homes. There was no way for women to avoid the conflict, or the disruptions and devastations it caused. As the leader of the state militia during the Revolution, Mary Silliman’s husband, Gold, was absent from their home for much of the conflict. On the morning of July 7, 1779, when a British fleet attacked nearby Fairfield, Connecticut, it was Mary who calmly evacuated her household, including her children and servants, to North Stratford. When Gold was captured by loyalists and held prisoner, Mary, six months pregnant with their second child, wrote letters to try and secure his release. When such appeals were ineffectual, Mary spearheaded an effort to capture a prominent Tory leader to exchange for her husband’s freedom.

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 1 Men and women together struggled through years of war and hardship. But even victory brought uncertainty. The Revolution created as many opportunities as it did corpses, and it was left to the survivors to determine the future of the new nation.

¶ 78

Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0

Another John Trumbull piece commissioned for the Capitol in 1817, this painting depicts what would be remembered as the moment the new United States became a republic. On December 23, 1783, George Washington, widely considered the hero of the Revolution, resigned his position as the most powerful man in the former thirteen colonies. Giving up his role as Commander-in-Chief of the Army insured that civilian rule would define the new nation, and that a republic would be set in place rather than a dictatorship. John Trumbull, General George Washington Resigning His Commission, c. 1817-1824. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:General_George_Washington_Resigning_his_Commission.jpg.

Another John Trumbull piece commissioned for the Capitol in 1817, this painting depicts what would be remembered as the moment the new United States became a republic. On December 23, 1783, George Washington, widely considered the hero of the Revolution, resigned his position as the most powerful man in the former thirteen colonies. Giving up his role as Commander-in-Chief of the Army insured that civilian rule would define the new nation, and that a republic would be set in place rather than a dictatorship. John Trumbull, General George Washington Resigning His Commission, c. 1817-1824. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:General_George_Washington_Resigning_his_Commission.jpg.

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0

VI. The Consequences of the American Revolution

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 1 Like the earlier distinction between “origins” and “causes,” the Revolution also had short- and long-term consequences. Perhaps the most important immediate consequence of declaring independence was the creation of state constitutions in 1776 and 1777. The Revolution also unleashed powerful political, social, and economic forces that would transform the post-Revolution politics and society, including increased participation in politics and governance, the legal institutionalization of religious toleration, and the growth and diffusion of the population. The Revolution also had significant short-term effects on the lives of women in the new United States of America. In the long-term, the Revolution would also have significant effects on the lives of slaves and free blacks as well as the institution of slavery itself. It also affected Native Americans by opening up western settlement and creating governments hostile to their territorial claims. Even more broadly, the Revolution ended the mercantilist economy, opening new opportunities in trade and manufacturing.

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0 The new states drafted written constitutions, which, at the time, was an important innovation from the traditionally unwritten British Constitution. Most created weak governors and strong legislatures with regular elections and moderately increased the size of the electorate. A number of states followed the example of Virginia, which included a declaration or “bill” of rights in their constitution designed to protect the rights of individuals and circumscribe the prerogative of the government. Pennsylvania’s first state constitution was the most radical and democratic. They created a unicameral legislature and an Executive Council but no genuine executive. All free men could vote, including those who did not own property. Massachusetts’ constitution, passed in 1780, was less democratic but underwent a more popular process of ratification. In the fall of 1779, each town sent delegates––312 in all––to a constitutional convention in Cambridge. Town meetings debated the constitution draft and offered suggestions. Anticipating the later federal constitution, Massachusetts established a three-branch government based on checks and balances between the branches. Unlike some other states, it also offered the executive veto power over legislation. 1776 was the year of independence, but it was also the beginning of an unprecedented period of constitution-making and state building.

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0 The Continental Congress ratified the Articles of Confederation in 1781. The Articles allowed each state one vote in the Continental Congress. But the Articles are perhaps most notable for what they did not allow. Congress was given no power to levy or collect taxes, regulate foreign or interstate commerce, or establish a federal judiciary. These shortcomings rendered the post-war Congress rather impotent.

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 1 Political and social life changed drastically after independence. Political participation grew as more people gained the right to vote. In addition, more common citizens (or “new men”) played increasingly important roles in local and state governance. Hierarchy within the states underwent significant changes. Locke’s ideas of “natural law” had been central to the Declaration of Independence and the state constitutions. Society became less deferential and more egalitarian, less aristocratic and more meritocratic.

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0 The Revolution’s most important long-term economic consequence was the end of mercantilism. The British Empire had imposed various restrictions on the colonial economies including limiting trade, settlement, and manufacturing. The Revolution opened new markets and new trade relationships. The Americans’ victory also opened the western territories for invasion and settlement, which created new domestic markets. Americans began to create their own manufacturers, no longer content to reply on those in Britain.

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0 Despite these important changes, the American Revolution had its limits. Following their unprecedented expansion into political affairs during the imperial resistance, women also served the patriot cause during the war. However, the Revolution did not result in civic equality for women. Instead, during the immediate post-war period, women became incorporated into the polity to some degree as “republican mothers.” These new republican societies required virtuous citizens and it became mothers’ responsibility to raise and educate future citizens. This opened opportunity for women regarding education, but they still remained largely on the peripheries of the new American polity.

¶ 86

Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0

While in the 13 colonies boycotting women were seen as patriots, they were mocked in British prints like this one as immoral harlots sticking their noses in the business of men. Philip Dawe, “A Society of Patriotic Ladies at Edenton in North Carolina, March 1775. Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/388959.

While in the 13 colonies boycotting women were seen as patriots, they were mocked in British prints like this one as immoral harlots sticking their noses in the business of men. Philip Dawe, “A Society of Patriotic Ladies at Edenton in North Carolina, March 1775. Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/388959.

¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0 Slaves and free blacks also impacted (and were impacted by) the Revolution. The British were the first to recruit black (or “Ethiopian”) regiments, as early as Dunmore’s Proclamation of 1775 in Virginia, which promised freedom to any slaves who would escape their masters and join the British cause. At first, Washington, a slaveholder himself, resisted allowing free blacks and former slaves to join the Continental Army, but he eventually relented. In 1775, Peter Salem’s master freed him to fight with the militia. Salem faced British Regulars in the battles at Lexington and Bunker Hill, where he fought valiantly with around three-dozen other black Americans. Salem not only contributed to the cause, but he earned the ability to determine his own life after his enlistment ended. Salem was not alone, but many more slaves seized upon the tumult of war to run away and secure their own freedom directly.

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0 Between 30,000 and 100,000 slaves deserted their masters during the war. In 1783, thousands of Loyalist former slaves fled with the British army. They hoped that the British government would uphold the promise of freedom and help them establish new homes elsewhere in the Empire. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the war, demanded that British troops leave runaway slaves behind, but the British military commanders upheld earlier promises and evacuated thousands of freedmen, transporting them to Canada, the Caribbean, or Great Britain. But black loyalists continued to face social and economic marginalization, including restrictions on land ownership. In 1792, Black loyalist and Baptist preacher David George resisted discrimination, joining a colonization project that led nearly 1,200 former black Americans from Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone, in Africa.

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0 The fight for liberty led some Americans to manumit their slaves, and most of the new northern states soon passed gradual emancipation laws. Manumission also occurred in the Upper South, but in the Lower South, some masters revoked their offers of freedom for service, and other freedmen were forced back into bondage. The Revolution’s rhetoric of equality created a “revolutionary generation” of slaves and free blacks that would eventually encourage the antislavery movement. Slave revolts began to incorporate claims for freedom based on revolutionary ideals. In the long-term, the Revolution failed to reconcile slavery with these new egalitarian republican societies, a tension that eventually boiled over in the 1830s and 1840s and effectively tore the nation in two in the 1850s and 1860s.

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 0 Native Americans, too, participated in and were affected by the Revolution. Many Native American tribes and confederacies, such as the Shawnee, Creek, Cherokee, and Iroquois, sided with the British. They had hoped for a British victory that would continue to restrain the land-hungry colonial settlers from moving west beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Unfortunately, the Americans’ victory and Native Americans’ support for the British created a pretense for justifying the rapid, and often brutal expansion into the western territories. Native American tribes would continue to be displaced and pushed further west throughout the nineteenth century. Ultimately, American independence marked the beginning of the end of what had remained of Native American independence.

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0

VII. Conclusion

¶ 92 Leave a comment on paragraph 92 0 The American Revolution freed colonists from British rule, allowing them to create their own societies founded on the (albeit limited) principals of popular sovereignty and civic equality. But it also offered the first blow in what historians have called “the age of democratic revolutions.” After the American Revolution, revolutions also broke out in France, then Haiti, and then South America, all drawing in some inspiration from the United States. The American Revolution also wrought significant changes to the British Empire, causing many British historians to characterize the pre-Revolution empire as “the first British Empire” and the post-Revolution empire as “the second British Empire.” The American Revolution was a global event, effecting and being affected by developments throughout the world.

¶ 93 Leave a comment on paragraph 93 1 Historians have long argued about the causes and character of the American Revolution. Was the Revolution caused by British imperial policy or internal tensions within the colonies? Were colonists primarily motivated by ideas or economic interest? Was the Revolution radical or conservative? Questions about the Revolution preoccupy more than historians, however. From Abraham Lincoln quoting the Declaration of Independence in his “Gettysburg Address” to the modern-day “Tea Party,” the Revolution has remained at the center of American political culture throughout the nation’s entire history. How one understands the Revolution continues to inform how one defines what it means to be “American.” The Revolution did not end all social and civic inequalities in the new nation, but the rhetoric of equality encapsulated in the Declaration of Independence highlighted those inequalities, eventually aiding the abolitionist movement of the early nineteenth century and the women’s rights movements of the 1840s and 1910s. The revolutionaries broke new ground, and had to make it up as they went along. In many ways, Americans have done the same ever since.

I think that the photographs in this chapter relate to the text but does not explain how it relates to the text. When I look at the picture I want it to summarize some of the text but in this case I do not think that these photographs match up to the text.