18. Capital and Labor

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

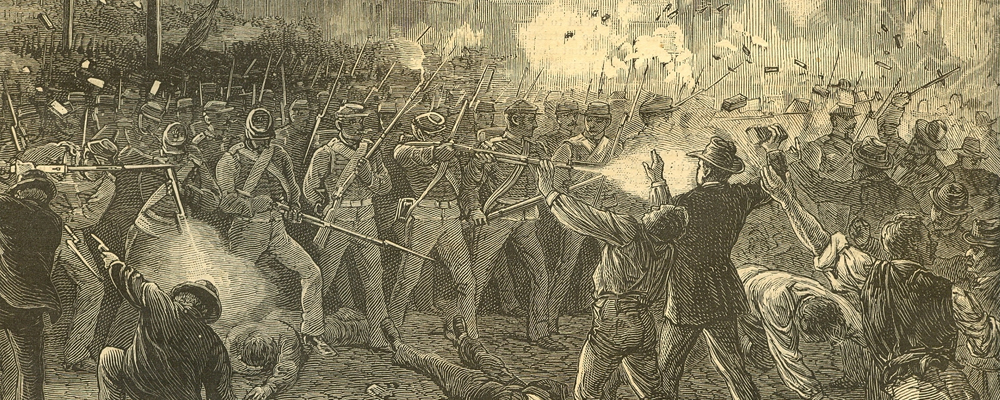

A Maryland National Guard unit fires upon strikers during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Harper’s Weekly, via Wikimedia.

A Maryland National Guard unit fires upon strikers during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Harper’s Weekly, via Wikimedia.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 *Click here to view the current published draft of this chapter*

I. Introduction

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 heralded a new era of labor conflict in the United States. That year, mired in the stagnant economy that followed the bursting of the railroads’ financial bubble in 1873, rail lines slashed workers’ wages (even, workers complained, as they reaped enormous government subsidies and paid shareholders lucrative stock dividends). Workers struck from Baltimore to St. Louis, shutting down railroad traffic—the nation’s economic lifeblood—across the country.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Panicked business leaders and friendly political officials reacted quickly. When local police forces were unwilling or incapable of suppressing the strikes, governors called out state militias to break the strikes and restore rail service. Many strikers destroyed rail property rather than allow militias to reopen the rails. The protests approached a class war. The governor of Maryland deployed the state’s militia. In Baltimore the militia fired into a crowd of striking workers, killing eleven and wounding many more. Strikes convulsed towns and cities across Pennsylvania. The head of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Thomas Andrew Scott, suggested that, if workers were unhappy with their wages, they should be given “a rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread.” Law enforcement in Pittsburgh refused, so the governor called out the state militia, who killed twenty strikers with bayonets and rifle fire. A month of chaos erupted there. Strikers set fire to the city, destroying dozens of buildings, over a hundred engines, and over a thousand cars. In Reading, strikers destroyed rail property and an angry crowd bombarded militiamen with rocks and bottles. The militia fired into the crowd, killing ten. Strikers in St. Louis seized rail depots and declared for the eight-hour day and the abolition of child labor. Troops and vigilantes fought their way into the depot, killing eighteen and breaking the strike. Rail lines were shut down all across neighboring Illinois. Coal miners struck in sympathy. Tens of thousands gathered to protest under the aegis of the Workingmen’s Party. Twenty protestors were killed in Chicago by special police and militiamen.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

Courts, police, and state militias all targeted the strikers, but it was federal troops that finally crushed them. On the orders of the President, American soldiers arrived in striking cities all across northern rail lines. When Pennsylvania militiamen were unable to contain the strikes, federal troops stepped in. When militia in West Virginia refused to break the strike, federal troops broke it. Soldiers moved from town to town, suppressing the protests and reopening the rail lines. Six weeks after it had begun, the strike had been defeated.

Nearly 100 Americans died in “The Great Upheaval.” Workers destroyed nearly $40 million worth of property. The strike had galvanized the country. It convinced laborers of the need for institutionalized unions, persuaded businesses of the need for political influence and government aid, and foretold of the next half-century of labor conflict in the United States.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

II. The March of Capital

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Labor unrest grew alongside industrialization. The greatest strikes first hit the railroads because no other industry had so effectively marshalled capital, government favors, bureaucratic management, and the sheer size to manage them all. Workers perceived their new powerlessness in the coming industrial order. Their skills mattered less and less in an industrialized mass produced economy, and their power as individuals seemed ever smaller and more insignificant as companies grew in size and power and their managers grew flush with wealth and influence. Long hours, dangerous working conditions, and the difficulty of supporting a family on the meager and unpredictable wages of industrial labor all compelled labor to organize and battle against the power of capital.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 The decades after the Civil War revolutionized American industry. Technological innovations and national investments slashed the costs of production and distribution. New administrative frameworks sustained the weight of vast firms. National credit agencies eased the uncertainties surrounding the rapid movement of capital between investors, manufacturers, and retailers. Plummeting transportation and communication costs opened new national media, which advertising agencies used to nationalize products.

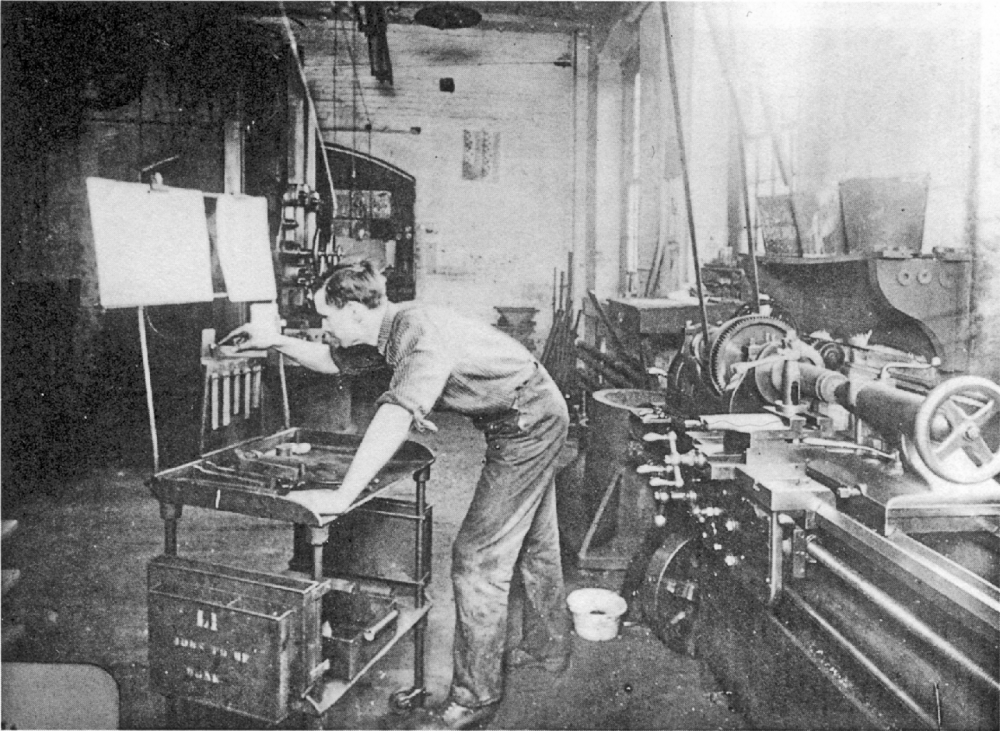

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 By the turn of the century, corporate leaders and wealthy industrialists embraced the new principles of “scientific management,” or “Taylorism,” after its noted proponent, Frederick Taylor. The precision of steel parts, the harnessing of electricity, the innovations of machine tools, and the mass markets wrought by the railroads offered new avenues for efficiency. To match the demands of the machine age, Taylor said, firms needed a scientific organization of production. He urged all manufacturers to increase efficiency by subdividing tasks. Rather than having thirty mechanics individually making thirty machines, for instance, a manufacturer could assign thirty laborers to perform thirty distinct tasks. Such a shift would not only make workers as interchangeable as the parts they were using, it would also dramatically speed up the process of production. If managed by trained experts, specific tasks could be done quicker and more efficiently. Taylorism increased the scale and scope of manufacturing and allowed for the flowering of mass production. Building upon the use of interchangeable parts in Civil War era weapons manufacturing, American firms advanced mass production techniques. Singer sewing machines, Chicago packers’ disassembly lines, the McCormick grain reaper, Duke cigarette rollers: all realized unprecedented new efficiencies and achieved unheard levels of production that propelled their companies into the forefront of American business. Henry Ford made the assembly line famous, allowing the production of automobiles to skyrocket as their cost plummeted, but American firms had been paving the way for decades.

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

Companies throughout the United States adopted the practices of “Taylorism” at the turn of the century, making the work of laborers like this machinist at the Tabor Company remarkably efficient. Photograph, c. 1905. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Musterarbeitsplatz.png.

Companies throughout the United States adopted the practices of “Taylorism” at the turn of the century, making the work of laborers like this machinist at the Tabor Company remarkably efficient. Photograph, c. 1905. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Musterarbeitsplatz.png.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Cyrus McCormick had overseen the construction of mechanical reapers (used for harvesting wheat) for decades. He had relied upon skilled blacksmiths, skilled machinists, and skilled woodworkers to handcraft machines. But production was slow and the machines were expensive. The reapers enabled massive gains in grain farming, but their high cost and slow production times proved cost ineffective for most American wheat farmers. Then, in 1880, McCormick hired a production manager who had worked for Colt firearms. Soon his Chicago plant introduced new jigs, steel gauges, and pattern machines that could make precise duplicates of new interchangeable parts. The company made 21,000 machines in 1880. It made twice as many in 1885, and by 1889, less than a decade later, it was producing over 100,000 a year.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 The United States had lagged behind Britain, Germany, and France as recently as the 1860s. By 1900 it was the world’s leading manufacturing nation. By 1913 the United States produced one-third of the world’s industrial output—more than Britain, France, and Germany combined.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Firms such as McCormick’s realized massive economies of scale: after accounting for their massive investments in machines and marketing, each additional product cost the company relatively little in production costs. The bigger the company, then, the bigger the profits. New industrial companies therefore hungered for markets to keep their high-volume production facilities operating. Retailers and advertisers fed off of mass production and sustained the massive markets needed for mass production. Bureaucracy meanwhile allowed for the management of new giant firms. A new class of managers—who comprised what one economic historian called the “visible hand”—operated between the worlds of workers and owners and ensured the efficient operation and administration of mass production and mass distribution. Most important to the growth and maintenance of these new companies, however, were the legal creations used to protect investors and sustain the power of massed capital.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 The costs of mass production were prohibitive for all but the very wealthiest individuals, and, even then, the risks were too great for any individuals to bear fully. The corporation was ages old, but the rights of incorporation had generally been reserved for public works projects or government-sponsored monopolies. After the Civil War, however, the corporation, using new state incorporation laws passed during the Market Revolution of the early-nineteenth century, became a legal mechanism for nearly any enterprise to marshal vast amounts of capital while limiting the liability of shareholders. By washing their hands of legal and financial obligations while still retaining the right to profit massively, investors flooded corporations with new capital sufficient to industrialize.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 But a competitive marketplace threatened the promise of investments. Once the efficiency gains of mass production were realized, profit margins were undone by cutthroat competition, which kept costs low as price-cutting sunk into corporate profits. Companies rose and fell—and investors suffered losses—as manufacturing firms struggled to maintain supremacy in their particular industries. Economies of scale were a double-edged sword: while additional production provided immense profits, the high fixed costs of operating expensive factories dictated that even modest losses from selling under-priced goods were superior to not selling profitably priced goods at all. Market share was won and lost. Profits were unstable. American industrial firms therefore tried everything to avoid competition: they formed informal pools and trusts, they entered price-fixing agreements, they divided markets, and, when blocked by anti-trust laws and renegade price-cutting, merged into consolidations. Rather than suffer from ruinous competition, firms combined to bypass it altogether.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Between 1895 and 1904, and particularly in the four years between 1898 and 1902, a wave of mergers rocked the American economy. Competition melted away in what is known as “the great merger movement.” In nine years, 4000 companies disappeared. Nearly 20% of the American economy was folded into rival firms. In nearly every major industry, newly coalesced firms such as General Electric, and DuPont utterly dominated their market. Forty-one separate consolidations each controlled over 70% of the market in their industry. In 1901, for instance, financier J.P. Morgan oversaw the formation of United States Steel, built from eight leading steel companies. The second industrial revolution was built on steel and one firm—the world’s first billion-dollar company—controlled the market. The age of monopoly had arrived in force.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

III. The Rise of Inequality

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Industrial capitalism realized the greatest advances in efficiency and productivity that the world had ever seen. Massive new companies marshalled capital on an unprecedented scale and provided profits and made unheard-of fortunes. But it also created millions of low-paid, unskilled, unreliable jobs with long hours and dangerous working conditions. Industrial capitalism therefore confronted Gilded Age Americans with unprecedented inequalities. The sudden appearance of the extreme wealth of industrial and financial titans and the crippling squalor of the urban and rural poor shocked Americans.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 The great financial and industrial titans, the so-called “robber barons,” included railroad operators such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, oilmen such as J.D. Rockefeller, steel magnates such as Andrew Carnegie, and bankers such as J.P. Morgan, won fortunes that, adjusted for inflation are still among the largest the nation has ever seen. According to various measurements, in 1890 the wealthiest one-percent of Americans owned one-fourth of the nation’s assets; the top ten percent owned over seventy percent. And inequality advanced. By 1900, the richest ten percent controlled perhaps ninety percent of the nation’s wealth.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 As these vast new fortunes accumulated among a small number of wealthy Americans, new ideas arose to bestow moral legitimacy on runaway wealth. In 1859, British naturalist Charles Darwin published his theory of evolution by natural selection and the “survival of the fittest” in his On the Origin of Species. It was not until the 1870s, however, that those theories gained widespread traction among the majority of biologists, naturalists, and other scientists in the United States, and, in turn, challenged the social, political, and religious beliefs of many Americans. One of Darwin’s greatest popularizers, the British sociologist and biologist Herbert Spencer, applied Darwin’s theories of natural selection and the survival of the fittest to society. The fittest would demonstrate their superiority through economic success; social Darwinists believed that state welfare and private charity would lead to degeneration by perpetuating the survival of the weak.

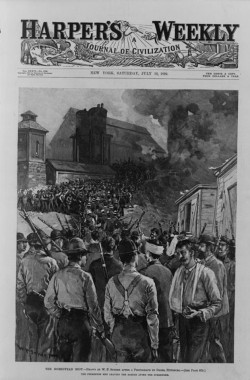

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 “There must be complete surrender to the law of natural selection,” the Baltimore Sun journalist H. L. Mencken wrote in 1907. “All growth must occur at the top. The strong must grow stronger, and that they may do so, they must waste no strength in the vain task of trying to uplift the weak.” By the time Mencken wrote those words, the ideas of social Darwinism had spread among wealthy Americans and their defenders. Social Darwinism identified a divine order in nature that extended from the law of the cosmos to the workings of industrial society. All species and all societies, including modern humans, it said, were governed by a relentless competitive struggle for survival, and inequality of outcomes was to be not merely tolerated, but encouraged and celebrated, as it signified the progress of species and societies. Spencer’s major work, Synthetic Philosophy, sold nearly 400,000 copies in America by the time of his death in 1903. Gilded Age industrial elites, such as steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, inventor Thomas Edison, and Standard Oil’s John D. Rockefeller, were among Spencer’s prominent followers. Other American thinkers, such as Yale’s William Graham Sumner, echoed these ideas. Sumner said, “before the tribunal of nature a man has no more right to life than a rattlesnake; he has no more right to liberty than any wild beast; his right to pursuit of happiness is nothing but a license to maintain the struggle for existence.”

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 But not all so eagerly welcomed inequalities. The spectacular growth of the U.S. economy and the vast inequality in living conditions and income that followed confounded many Americans. But as industrial capitalism overtook the nation, it shaped national politics as well. Although both major political parties facilitated the rise of big business and used state power to support the interests of capital against labor, big business looked primarily to the Republican Party.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 The Republicans had risen as an antislavery party committed to “free labor,” but they were also ardent supporters of American business. Abraham Lincoln had been a corporate lawyer who defended railroads, and the Republican national government took advantage of the absence of southern Democrats to push through a pro-business agenda during the Civil War. The Republican congress gave millions of acres and dollars to railroad companies. Republicans became the party of business. And they dominated American politics throughout the Gilded Age and the first several decades of the twentieth century. Out of sixteen presidential elections between the Civil War and the Great Depression, Republican candidates won all but four. Likewise, Republicans controlled the Senate in twenty-seven out of thirty-two sessions in the same period. One result of this prolonged pro-business hegemony was the protective tariff, a policy Southern planters had vehemently opposed before the war but now could do nothing to prevent. It became the foundation of a new American industrial order. And Spencer’s social Darwinism provided justification for national policies that minimized government interference in the economy for anything other than the protection and support of business, enabling the formation of large trusts and monopolies, and ensuring, as best they could, the stability of the American banking system.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

IV. The Labor Movement

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 The ideas of social Darwinism attracted little support among the mass of American industrial laborers. Workers toiled in difficult jobs for long hours and little pay. Workers labored sixty hours a week and could still expect their annual income to fall below the poverty line. Among the working poor, wives and children were forced into the labor market. Mechanization and mass production threw skilled laborers into unskilled positions. Industrial work ebbed and flowed with the economy. The typical industrial laborer could expect to be unemployed one month out of the year. Crowded cities, meanwhile, could ill accommodate growing urban populations and skyrocketing rents trapped families in crowded slums.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 1 Strikes therefore ruptured American industry throughout the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Workers seeking higher wages, shorter hours, and safer working conditions had struck throughout the antebellum era, but organized craft and trade unions were typically fleeting and transitory. The Civil War and Reconstruction seemed to briefly distract the nation from the plight of labor, but the end of the sectional crisis and the explosive growth of big business, unprecedented fortunes, and a vast industrial workforce in the last quarter of the nineteenth century enabled the rise of a vast new American labor movement.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 The failure of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 convinced workers of the need to organize. Union memberships began to climb. The Knights of Labor enjoyed considerable success in the early 1880s, due in part to its efforts to unite skilled and unskilled workers. It welcomed all laborers, including women (the Knights barred lawyers, bankers, and liquor dealers). By 1886 the Knights had over 700,000 members. The Knights envisioned a cooperative producer-centered society that rewarded labor, but despite this sweeping vision, the Knights focused on practical gains to be won through the organization of workers into local unions.

¶ 28

Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

A 1892 cover of Harper’s Weekly depicted the result of the Homestead Riot, showing the Pinkerton men are seen leaving the barge in defeat after surrendering to the Carnegie steel mill workers. The Pinkerton men, who at the forefront appear calm and composed, are walked through a violent mob of mill workers as they depart from the scene.W.P. Synder (artist) after a photograph by Dabbs, “The Homestead Riot,” 1892. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/00650151/.

A 1892 cover of Harper’s Weekly depicted the result of the Homestead Riot, showing the Pinkerton men are seen leaving the barge in defeat after surrendering to the Carnegie steel mill workers. The Pinkerton men, who at the forefront appear calm and composed, are walked through a violent mob of mill workers as they depart from the scene.W.P. Synder (artist) after a photograph by Dabbs, “The Homestead Riot,” 1892. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/00650151/.

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 In Marshall, Texas, in the spring of 1886, one of Jay Gould’s rail companies fired a Knights of Labor union member for attending a union meeting. His local union struck and soon others joined. Nearly 200,000 workers struck against Jay Gould’s rail lines from Texas and Arkansas into Missouri, Kansas, and Illinois. Gould hired strikebreakers and the Pinkerton Detective Agency, a kind of security contractor, to break up the strikes and get the rails moving again. State militias were called in support of Gould’s companies. The Texas governor called out the Texas Rangers. Workers countered by destroying property, which only won them negative headlines and seemingly justified the use of strikebreakers and militiamen. The strike undermined the Knights of Labor, but the organization regrouped. It set its eyes on the eight hour day.

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 In the summer 1886 the campaign for an eight-hour day, long a rallying cry that united American laborers, culminated in a national strike on May 1, 1886. Somewhere between 300,000 and 500,000 workers struck all across the country.

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 In Chicago, police forces killed several workers while breaking up protestors at the McCormick reaper works. Labor leaders and radicals called for a protest at Haymarket Square the following day, which police proceeded to break up as well. As they did, however, a bomb exploded and killed seven policemen and wounded scores more. Police fired into the crowd, killing four. The national media sensationalized the “Haymarket Riot” and helped Americans to associate unionism and radicalism. The deaths of the Chicago policemen sparked outrage across the nation. Eight Chicago anarchists were arrested and, despite direct evidence implicating them in the bombing, were charged and found guilty of conspiracy. Four were hanged (and one committed suicide before he could be). Membership in the Knights had peaked that year, but fell rapidly after Haymarket: the group became associated with violence and radicalism.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 The American Federation of Labor (AFL) emerged as an alternative to the radical vision of the Knights of Labor. An alliance of craft (skilled) unions, the AFL rejected the Knights’ expansive vision of a producerist economy and advocated “pure and simple trade unionism,” a program that aimed for practical gains (higher wages, fewer hours, and safer conditions) through a conservative approach that minimized striking. Workers, however, continued to strike.

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 In 1892, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers struck one of Carnegie’s steel mills in Homestead, Pennsylvania. After repeated wage cuts, workers occupied the mill. The plant’s operator, Henry Clay Frick, immediately called in hundreds of Pinkerton detectives but the steel workers fought the Pinkertons, who tried to land by river and were besieged by the striking steel workers. After several hours of pitched battle, the Pinkertons surrendered, ran a bloody gauntlet of workers, and were kicked out of the mill. But the Pennsylvania governor called the state militia, which broke the strike and reopened the mill. The union was nearly destroyed in the aftermath.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 Strikes continued to roll across the industrial landscape. In 1894, workers in George Pullman’s “Pullman Car” factories struck when he cut wages by a quarter but kept rents and utilities in his company town constant. The American Railway Union (ARU), led by Eugene Debs, launched a sympathy strike: the ARU would refuse to handle any Pullman cars on any rail line. Thousands of workers struck and national railroad traffic ground to a halt. Unlike nearly every other major strike, the governor of Illinois had sympathies with labor and refused to dispatch the state militia. Ultimately, it didn’t matter. In July, President Grover Cleveland dispatched thousands of American soldiers to break the strike. Meanwhile, a federal court had issued an injunction against Debs and the union’s leadership. The strike violated this injunction, and Debs was arrested and imprisoned. The strike evaporated without its leadership, but jail radicalized Debs, proving to him the law was merely a tool for capital in its struggle against labor.

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 The final two decades of the nineteenth century saw over 20,000 strikes and lockouts. Industrial laborers struggled to carve for themselves a piece of the prosperity lifting investors and much of the American middle class into unprecedented standards of living. But workers were not the only ones struggling to stay afloat in industrial America. Many Americans farmers also lashed out against the inequalities of the Gilded Age and saw political corruption as enabling economic theft.

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

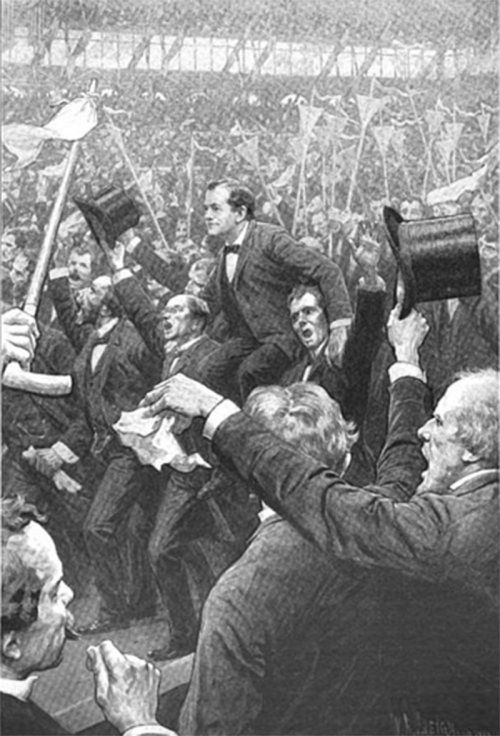

V. The Populist Movement

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 “Wall street owns the country,” the Populist leader Mary Elizabeth Lease told dispossessed farmers around 1890. “It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street, and for Wall Street.” Farmers, who remained a majority of the American population through the first decade of the twentieth century, were hit especially hard by industrialization. Expanding markets and technology that increased efficiency also decreased commodity prices. Further commercialization of agriculture put farmers in the hands of bankers, railroads, and various middle men. As the decades passed farmers fell ever farther into debt, lost their land, and entered the industrial workforce or, especially in the South, became landless farmworkers.

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 The rise of industrial giants reshaped the American countryside and the Americans who called it home. Railroad spurs, telegraph lines, and credit crept into farming communities and linked rural Americans, who still made up a majority of the country’s population, with towns, regional cities, the American financial centers of Chicago and New York, and, eventually, London. Meanwhile, improved farm machinery, easy credit, and the latest consumer goods flooded the countryside. New connections and new conveniences, however, came at a price.

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Farmers had always been dependent on the whims of the weather and local markets. But now they staked their financial security on a national economic system subject to rapid price swings, rampant speculation, and limited regulation. Their dissatisfaction with this often erratic and impersonal system put many of them at the forefront of what would become perhaps the most serious challenge to the political economy of Gilded Age America. Frustrated American farmers attempted to reshape the fundamental structures of the nation’s political and economic systems, systems they believed enriched parasitic bankers and industrial monopolists at the expense of the many laboring farmers who fed the nation by producing its many crops and farm goods. Organizationally, they launched their challenge first through the non-partisan Farmers’ Alliance and later through the People’s (or Populist) Party.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 Mass production and business consolidations spawned giant corporations that monopolized nearly every sector of the U.S. economy in the decades after the Civil War. In contrast, the economic power of the individual farmer sunk into oblivion. Threatened by ever-plummeting commodity prices and ever-rising indebtedness, Texas agrarians met in Lampasas in 1877 and organized the first Farmers’ Alliance to restore some economic power to farmers as they dealt with railroads, merchants, and bankers. If big business would rely on their numerical strength to exert their economic will, why shouldn’t farmers unite to counter that power? They could share machinery, bargain from wholesalers, and negotiate higher prices for their crops. Over the following years, organizers spread from town to town across the former Confederacy, Midwest, and the Great Plains, holding evangelical-style camp meetings, distributing pamphlets, and establishing over 1,000 Alliance newspapers. As the Alliance spread, so too did its near-religious vision of the nation’s future as a “cooperative commonwealth” that would protect the interests of the many from the predatory greed of the few. At its peak, the Farmers’ Alliance claimed 1,500,000 members meeting in 40,000 local sub-alliances.

¶ 41

Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0

The banner of the first Texas Farmers’ Alliance.

The banner of the first Texas Farmers’ Alliance.

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 The Alliance’s most innovative programs were a series of farmer’s cooperatives that enabled farmers to negotiate higher prices for their crops and lower prices for the goods they purchased. These cooperatives spread across the South between 1886 and 1892 and claimed more than a million members at its high point. While most failed financially, these “philanthropic monopolies,” as one Alliance speaker termed them, inspired farmers to look to large-scale organization to cope with their economic difficulties. But cooperation was only part of the Alliance message.

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 In the South, Alliance-backed Democratic candidates won 4 governorships and 48 congressional seats in 1890. But at a time when falling prices and rising debts conspired against the survival of family farmers, the two political parties seemed incapable of representing the needs of poor farmers. And so Alliance members organized a political party—the People’s Party, or the Populists, as they came to be known. The Populists attracted supporters across the nation by appealing to those convinced that there were deep flaws in the political economy of Gilded Age America, flaws that both political parties refused to address. Veterans of earlier fights for currency reform, disaffected industrial laborers, proponents of the benevolent socialism of Edward Bellamy’s popular Looking Backward, and the champions of Henry George’s farmer-friendly “single-tax” proposal joined Alliance members in the new party. The Populists nominated former Civil War general James B. Weaver as their presidential candidate at the party’s first national convention in Omaha, Nebraska, on July 4, 1892.

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 At that meeting the party adopted a platform that crystallized the Alliance’s cooperate program into a coherent political vision. The platform’s preamble, written by longtime political iconoclast and Minnesota populist Ignatius Donnelly, warned that “[t]he fruits of the toil of millions [had been] boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few.” Taken as a whole, the Omaha Platform and the larger Populist movement sought to counter the scale and power of monopolistic capitalism with a strong, engaged, and modern federal government. The platform proposed an unprecedented expansion of federal power. It advocated nationalizing the country’s railroad and telegraph systems to ensure that essential services would be run in the best interests of the people. In an attempt to deal with the lack of currency available to farmers, it advocated postal savings banks to protect depositors and extend credit. It called for the establishment of a network of federally-managed warehouses—called subtreasuries—which would extend government loans to farmers who stored crops in the warehouses as they awaited higher market prices. To save debtors it promoted an inflationary monetary policy by monetizing silver. Direct election of Senators and the secret ballot would ensure that this federal government would serve the interest of the people rather than entrenched partisan interests and a graduated income tax would protect Americans from the establishment of an American aristocracy. Combined, these efforts would, Populists believed, help to shift economic and political power back toward the nation’s producing classes.

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 In the Populists first national election campaign in 1892, Weaver received over one million votes (and 22 electoral votes), a truly startling performance that signaled a bright future for the Populists. And when the Panic of 1893 sparked the worst economic depression the nation had ever yet seen, the Populist movement won further credibility and gained even more ground. Kansas Populist Mary Lease, one of the movement’s most fervent speakers, famously, and perhaps apocryphally, called on farmers to “raise less corn and more Hell.” Populist stump speakers crossed the country, speaking with righteous indignation, blaming the greed of business elites and corrupt party politicians for causing the crisis fueling America’s widening inequality. Southern orators like Texas’ James “Cyclone” Davis and Georgian firebrand Tom Watson stumped across the South decrying the abuses of northern capitalists and the Democratic Party. Pamphlets such as W.H. Harvey’s Coin’s Financial School and Henry D. Lloyd’s Wealth against Commonwealth provided Populist answers to the age’s many perceived problems. The faltering economy combined with the Populist’s extensive organizing. In the 1894 elections, Populists elected six senators and seven representatives to Congress. The third party seemed destined to conquer American politics.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 The movement, however, still faced substantial obstacles, especially in the South. The failure of Alliance-backed Democrats to live up to their campaign promises drove some southerners to break with the party of their forefathers and join the Populists. Many, however, were unwilling to take what was, for southerners, a radical step. Southern Democrats, for their part, responded to the Populist challenge with electoral fraud and racial demagoguery. Both severely limited Populist gains. The Alliance struggled to balance the pervasive white supremacy of the American South with their call for a grand union of the producing class. American racial attitudes—and its virulent southern strain—simply proved too formidable. Democrats race-baited Populists and Populists capitulated. The Colored Farmers Alliance, which had formed as a segregated sister organization to the Southern Alliance, and had as many as 250,000 members at its peak, fell prey to racial and class-based hostility. The group went into rapid decline in 1891 when faced with the violent white repression of a number of Colored Alliance-sponsored cotton-picker strikes. Racial mistrust and division remained the rule, even among Populists, and even in North Carolina, where a political marriage of convenience between Populists and Republicans resulted in the election of Populist Marion Butler to the Senate. Populists opposed Democratic corruption, but this did not necessarily make them champions of interracial democracy. As Butler explained to an audience in Edgecome County, “[w]e are in favor of white supremacy, but we are not in favor of cheating and fraud to get it.” In fact, across much of the South, Populists and Farmers Alliance members were often at the forefront of the movement for disfranchisement and segregation.

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 Populism exploded in popularity. The first major political force to tap into the vast discomfort of many Americans with the disruptions wrought by industrial capitalism, the Populist Party seemed poise to capture political victory. And yet, even as Populism gained national traction, the movement was stumbling. The party’s often divided leadership found it difficult to shepherd what remained a diverse and loosely organized coalition of reformers towards unified political action. The Omaha platform was a radical document, and some state party leaders selectively embraced its reforms. More importantly, the institutionalized parties were still too strong, and the Democrats loomed, ready to swallow populist frustrations and inaugurate a new era of American politics.

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0

VI. William Jennings Bryan and the Politics of Gold

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) accomplished many different things in his life: he was a skilled orator, a Nebraska Congressman, a three-time presidential candidate, the U.S. Secretary of the State under Woodrow Wilson, and a lawyer who supported prohibition and opposed Darwinism (most notably in the 1925 Scopes “Monkey” Trial). In terms of his political career, he won national renown for his attack on the gold standard and his tireless promotion of free silver and policies for the benefit of the average American. Although Bryan was unsuccessful in winning the presidency, he forever altered the course of American political history.

¶ 50

Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0

With the country in financial chaos after the Panic of 1893, William Jennings Bryan arose as a political star when he advocated bimetallism – the acceptance of both gold and silver as legal tender. Bryan’s Cross of Gold speech at 1896 Democratic National Convention, which he concluded with the fiery statement that “you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold,” secured him the Democratic nomination for President in 1896. Artist’s conception of William Jennings Bryan after the Cross of Gold speech, 1900. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bryan_after_speech.png.

With the country in financial chaos after the Panic of 1893, William Jennings Bryan arose as a political star when he advocated bimetallism – the acceptance of both gold and silver as legal tender. Bryan’s Cross of Gold speech at 1896 Democratic National Convention, which he concluded with the fiery statement that “you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold,” secured him the Democratic nomination for President in 1896. Artist’s conception of William Jennings Bryan after the Cross of Gold speech, 1900. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bryan_after_speech.png.

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 Bryan was born in Salem, Illinois, in 1860 to a devout family with a strong passion for law, politics, and public speaking. At twenty, he attended Union Law College in Chicago and passed the bar shortly thereafter. After his marriage to Mary Baird in Illinois, Bryan and his young family relocated to Nebraska, where he won a reputation among the state’s Democratic Party leaders as an extraordinary orator. Bryan would later win recognition as one of the greatest speakers in American history.

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 When economic depressions struck the Midwest in the late 1880s, despairing farmers faced low crop prices and found few politicians on their side. While many rallied to the Populist cause, Bryan worked from within the Democratic Party, using the strength of his oratory. After delivering one speech, he told his wife, “Last night I found that I had a power over the audience. I could move them as I chose. I have more than usual power as a speaker… God grant that I may use it wisely.” He soon won election to the Nebraska House of Representatives, where he served for two terms. Although he lost a bid to join the Nebraska Senate, Bryan refocused on a much higher political position: the presidency of the United States. There, he believed he could change the country by defending farmers and urban laborers against the corruptions of big business.

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 In 1895-1896, Bryan launched a national speaking tour in which he promoted the free coinage of silver. He believed that “bimetallism,” by inflating American currency, could alleviate farmers’ debts. In contrast, Republicans championed the gold standard and a flat money supply. American monetary standards became a leading campaign issue. Then, in July 1896, the Democratic Party’s national convention met to settle upon a choice for their president nomination in the upcoming election. The party platform asserted that the gold standard was “not only un-American but anti-American.” Bryan spoke last at the convention. He astounded his listeners. At the conclusion of his stirring speech, he declared, “Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” After a few seconds of stunned silence, the convention went wild. Some wept, many shouted, and the band began to play “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” Bryan received the 1896 Democratic presidential nomination.

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 The Republicans ran William McKinley, an economic conservative that championed business interests and the gold standard. Bryan crisscrossed the country spreading the silver gospel. The election drew enormous attention and much emotion. According to Bryan’s wife, he received two thousand letters of support every day that year, an enormous amount for any politician, let alone one not currently in office. Yet Bryan could not defeat the McKinley. The pro-business Republicans outspent Bryan’s campaign fivefold. A notably high 79.3% of eligible American voters cast ballots and turnout averaged 90% in areas supportive of Bryan, but Republicans swayed the population-dense Northeast and Great Lakes region and stymied the Democrats. In early 1900, Congress passed the Gold Standard Act, which put the country on the gold standard, effectively ending the debate over the nation’s monetary policy. Bryan sought the presidency again in 1900 but was again defeated, as he would be yet again in 1908.

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 Bryan was among the most influential losers in American political history. When the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party nominated the Nebraska congressman in 1896, Bryan’s fiery condemnation of northeastern financial interests and his impassioned calls for “free and unlimited coinage of silver” coopted popular Populist issues. The Democrats stood ready to siphon off a large proportion the Populist’s political support. When the People’s Party held its own convention two weeks later, the party’s moderate wing, in a fiercely-contested move, overrode the objections of more ideologically pure Populists and nominated Bryan as the Populist candidate as well. This strategy of temporary “fusion” movement fatally fractured the movement and the party. Populist energy moved from the radical-yet-still-weak People’s Party to the more moderate-yet-powerful Democratic Party. And although at first glance the Populist movement appears to have been a failure—its minor electoral gains were short-lived, it did little to dislodge the entrenched two-party system, and the Populist dream of a cooperative commonwealth never took shape—yet, in terms of lasting impact, the Populist Party proved the most significant third-party movement in American history. The agrarian revolt would establish the roots of later reform and the majority of policies outlined within the Omaha Platform would eventually be put into law over the following two decades under the management of middle-class reformers. In large measure, the Populist vision laid the intellectual groundwork for the coming progressive movement.

¶ 56

Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0

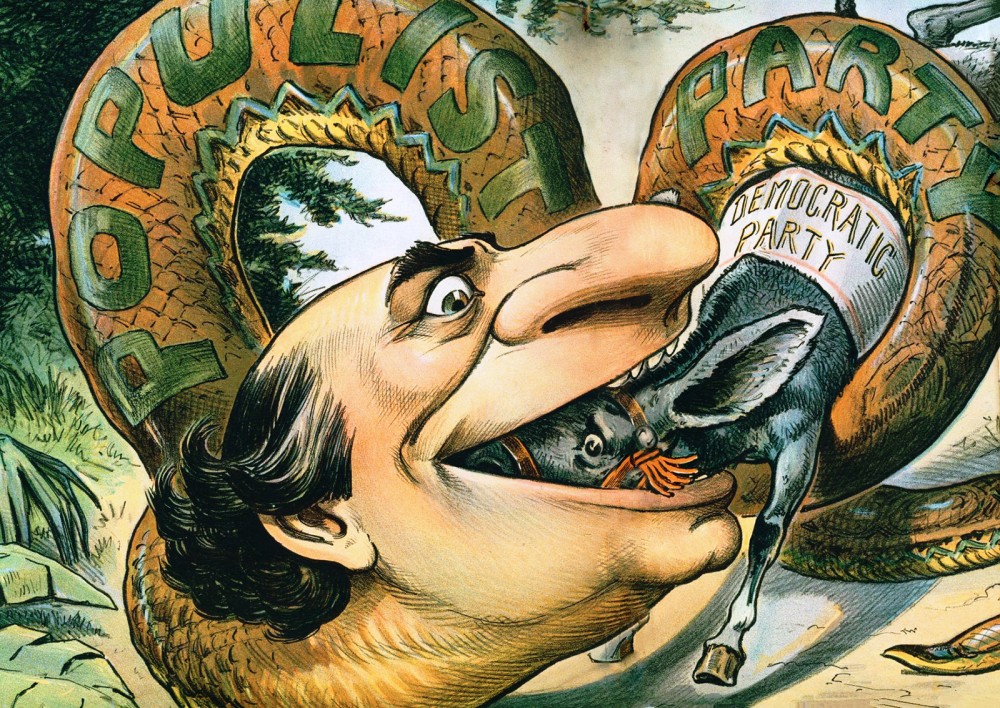

William Jennings Bryan espoused Populists politics while working within the two-party system as a Democrat. Republicans characterized this as a kind hijacking by Bryan, arguing that the Democratic Party was now a party of a radical faction of Populists. The pro-Republican magazine Judge rendered this perspective in a political cartoon showing Bryan (representing Populism writ large) as huge serpent swallowing a bucking mule (representing the Democratic party). Political Cartoon, Judge, 1896. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bryan,_Judge_magazine,_1896.jpg.

William Jennings Bryan espoused Populists politics while working within the two-party system as a Democrat. Republicans characterized this as a kind hijacking by Bryan, arguing that the Democratic Party was now a party of a radical faction of Populists. The pro-Republican magazine Judge rendered this perspective in a political cartoon showing Bryan (representing Populism writ large) as huge serpent swallowing a bucking mule (representing the Democratic party). Political Cartoon, Judge, 1896. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bryan,_Judge_magazine,_1896.jpg.

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0

VII. Early 20th Century Socialism

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 1 Others, however, refused to join the two parties and continued the Populists’ radical political tradition, this time not among old stock American farmers but among urban laborers. The Socialist Party of America was founded in 1901, part of a larger socialist movement that, over the course of twenty years, made significant gains in its attempt to transform American economic life. Socialist mayors were elected in 33 cities and towns, ranging from Berkeley, California to Schenectady, New York, and two—Victor Berger from Wisconsin and Meyer London from New York—won congressional seats. All told, over 1000 American socialist candidates won various political offices. Julius A. Wayland, editor of the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason, proclaimed that “socialism is coming. It’s coming like a prairie fire and nothing can stop it…you can feel it in the air.” By 1913 there were 150,000 members of the Socialist Party and in 1912 Eugene V. Debs, the Indiana-born Socialist Party candidate for president, received almost one million votes, or six percent of the total.

¶ 59

Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0

Victor Berger, who would be one of only two Socialist politicians elected to Congress, helped form the Socialist Party of America and spread its gospel as an influential socialist journalist in Wisconsin. Harris & Ewing (photographer), “BERGER, VICTOR L. HONORABLE,” between 1905 and 1945. Library of Congress.

Victor Berger, who would be one of only two Socialist politicians elected to Congress, helped form the Socialist Party of America and spread its gospel as an influential socialist journalist in Wisconsin. Harris & Ewing (photographer), “BERGER, VICTOR L. HONORABLE,” between 1905 and 1945. Library of Congress.

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0 The Socialist Movement arose in response to America’s new industrial economy. Socialists argued that wealth and power were consolidated in the hands of too few individuals, that monopolies and trusts controlled too much of the economy, that owners and investors grew rich at the expense of the very workers who produced their wealth, and that workers, despite massive productivity gains and rising national wealth, still suffered from low pay, long hours, and unsafe working conditions. Karl Marx had described the new industrial economy as a worldwide class struggle between the “bourgeoisie” who owned the means of production, such as factories and farms, and the “proletariat,” factory workers and tenant farmers who worked only for the wealth of others. According to Eugene Debs, socialists sought “the overthrow of the capitalist system and the emancipation of the working class from wage slavery.” Under an imagined socialist cooperative commonwealth, the means of production would be owned collectively, ensuring that all men and women received a fair wage for their labor. According to socialist organizer and newspaper editor Oscar Ameringer, socialists wanted “ownership of the trust[s] by the government, and the ownership of the government by the people.”

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 1 The Socialist Movement drew from a diverse constituency. Party membership was open to all regardless of race, gender, class, ethnicity, or religion. Many prominent Americans, such as Helen Keller, Upton Sinclair, and Jack London, became socialists. They were joined by anonymous American workers, by lumberjacks from the Northwest, miners from the West, tenant farmers in the South and Southwest, small farmers from the Midwest, and factory workers from the Northeast. All united under the red flag of socialism. Ultimately, though, a combination of internal disagreements over ideology and tactics, government repression, the co-optation of socialist policies by progressive reformers, and perceived incompatibilities between socialism and American values sunk the party until it was largely dismantled by the early 1920s.

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0

VIII. Conclusion

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 The march of capital transformed patterns of American labor. While a select few enjoyed historically unparalleled levels of wealth, and an ever-growing slice of middle-class workers possessed an ever more comfortable standard of living, vast numbers of farmers lost their land while a growing working class struggled to earn wages sufficient to support families and justify their labor. Industrial capitalism brought wealth and it brought poverty, it created owners and investors and it created employees. Whether winners or losers in the new American economy, Americans of all stripes had to reckon with the new ways of life unleashed by industrialization.

As you give notice to the rise of the labor movement it is my opinion that the identification that the sectional shift of the textile industry from north to south should also be identified as it was also a contributor to the formation of labor unions. “Explosive growth of big business” effectively played a role in the stimulation of the post-Civil War economy of the south. For example, as northern unions pushed for higher wages, better hours, and overall better working conditions, southern states courted northern corporations to open branches in the south. A textile firm known as The Dwight Manufacturing Company succumbed to such an opportunity when it opened its own southern branch. As this sectional shift proceeded, companies would sometimes establish their southern branch as their headquarters as was the case with The Dwight Manufacturing Company. I would also like to add that the ability of corporations to uproot and replant in the south was less likely in most cases. For example, by identifying The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, it must be noted that the mobility of such a market would make restructuring very strenuous. Through the collaboration of workers and owners, the expanse of territory the industry covers as well as the diversity of public influences would add to the complexity of the goals that the Labor Movement aimed to achieve.