12. Manifest Destiny

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, 1862. Mural, United States Capitol

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, 1862. Mural, United States Capitol

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 *Click here to view the current published draft of this chapter*

I. Introduction

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 John Louis O’Sullivan, a popular editor and columnist articulated the long-standing American belief in the God-given mission of the United States to lead the world in the peaceful transition to democracy. In a little read essay printed in The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, O’Sullivan outlined the importance of annexing Texas to the United States:

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 Why, were other reasoning wanting, in favor of now elevating this question of the reception of Texas into the Union, out of the lower region of our past party dissensions, up to its proper level of a high and broad nationality, it surely is to be found, found abundantly, in the manner in which other nations have undertaken to intrude themselves into it, between us and the proper parties to the case, in a spirit of hostile interference against us, for the avowed object of thwarting our policy and hampering our power, limiting our greatness and checking the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions. John Louis O’Sullivan

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 O’Sullivan and many others viewed expansion as necessary to achieve America’s destiny and protect America’s interests. The 1840s fused this religious call to spread democracy with the reality of settlers pressing west.

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

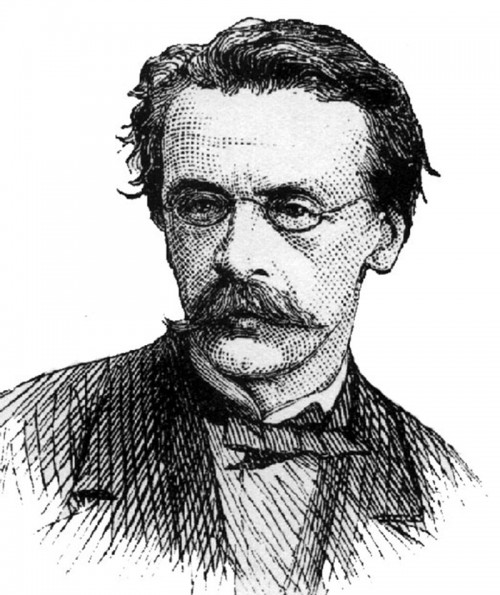

John O’Sullivan, shown here in a 1874 Harper’s Weekly sketch, coined the phrase “manifest destiny” in an 1845 newspaper article. Wikimedia.

John O’Sullivan, shown here in a 1874 Harper’s Weekly sketch, coined the phrase “manifest destiny” in an 1845 newspaper article. Wikimedia.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Manifest Destiny was a widely-held but vaguely-defined belief system which embraced several core beliefs. First, many Americans believed that the strength of American values and institutions justified moral claims to leadership. Second, the lands on the North American continent west of the Mississippi River (and later into the Caribbean) were destined for political and agricultural improvement. Third, Americans who supported expansion believed that God and the Constitution ordained an irrepressible destiny to accomplish redemption and democratization.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 The Young America movement, strongest among members of the Democratic Party, embraced the nation’s economic, intellectual, and literary bonds in order to downplay the increasingly rancorous debate over slavery. Young Americans across the political spectrum sought to reinvigorate republicanism by emphasizing territorial expansion, democratic participation, economic interdependency, and avoiding the slavery issue. Poet Ralph Waldo Emerson (pictured) captured the political outlook of this new young generation in speech he delivered in 1844 entitled “The Young American”:

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 In every age of the world, there has been a leading nation, one of a more generous sentiment, whose eminent citizens were willing to stand for the interests of general justice and humanity, at the risk of being called, by the men of the moment, chimerical and fantastic. Which should be that nation but these States? Which should lead that movement, if not New England? Who should lead the leaders, but the Young American? Ralph Waldo Emerson

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 However, some Americans disapproved of aggressive expansion. For opponents of manifest destiny, the lofty rhetoric of the Young Americans actually just defended American imperialism. Many members of the Whig Party (and later the Republican Party) demanded that the United States’ mission was to lead by moral and democratic example rather than through conquest. Abraham Lincoln summed up this criticism of with a fair amount of sarcasm during a speech in 1859:

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 He (the Young American) owns a large part of the world, by right of possessing it; and all the rest by right of wanting it, and intending to have it…Young America had “a pleasing hope — a fond desire — a longing after” territory. He has a great passion — a perfect rage — for the “new”; particularly new men for office, and the new earth mentioned in the revelations, in which, being no more sea, there must be about three times as much land as in the present. He is a great friend of humanity; and his desire for land is not selfish, but merely an impulse to extend the area of freedom. He is very anxious to fight for the liberation of enslaved nations and colonies, provided, always, they have land…As to those who have no land, and would be glad of help from any quarter, he considers they can afford to wait a few hundred years longer. In knowledge he is particularly rich. He knows all that can possibly be known; inclines to believe in spiritual trappings, and is the unquestioned inventor of “Manifest Destiny.” Abraham Lincoln

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Westward expansion, fueled by the principles of manifest destiny, exacerbated the slavery question and threatened the United States’ supposed sacred promise to the peoples of the world.

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0

Columbia, the female figure of America, leads Americans into the West and into the future by carrying the values of republicanism (as seen through her Roman garb) and progress (shown through the inclusion of technological innovations like the telegraph) and clearing native peoples and animals, seen being pushed into the darkness. John Gast, Manifest Destiny, 1872. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:American_progress.JPG.

Columbia, the female figure of America, leads Americans into the West and into the future by carrying the values of republicanism (as seen through her Roman garb) and progress (shown through the inclusion of technological innovations like the telegraph) and clearing native peoples and animals, seen being pushed into the darkness. John Gast, Manifest Destiny, 1872. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:American_progress.JPG.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

II. Antebellum Western Migration

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 After the War of 1812, Americans settled the Great Lakes region rapidly thanks in part to aggressive land sales by the federal government. Selling federal lands, mostly ceded by American Indians, was a major source of revenue in the era and officials were eager to survey and sell large parcels for new settlers. Missouri’s admission as a slave state presented the first major crisis over westward migration and American expansion in the antebellum period. Farther north, lead and iron ore mining spurred development in Wisconsin. By the 1830s and 1840s, increasing numbers of German and Scandinavian immigrants joined easterners in settling the Upper Mississippi watershed. Little settlement occurred west of Missouri as migrants viewed the Great Plains as a barrier to farming, the Rocky Mountains as undesirable to all but fur traders, and local American Indians as too powerful to allow white expansion.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 “Do not lounge in the cities!” commanded publisher Horace Greeley in 1841, “There is room and health in the country, away from the crowds of idlers and imbeciles. Go west, before you are fitted for no life but that of the factory.” The New York Tribune often argued that American exceptionalism required the United States to benevolently conquer the continent. However, the vast west was not empty. Native Americans controlled much of the land east of the Mississippi River and almost all the west. Expansion hinged on a federal policy of Indian removal.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

III. Indian Removal

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Florida was an early test case for the Americanization of new lands. Florida held strategic value for the young nation’s growing economic and military interests in the Caribbean. The most important factors that led to the annexation of Florida were Spanish neglect of the region and the defeat of Native American tribes who controlled large portions of the territory until evicted by U.S. troops during three Seminole Wars between 1817 and 1858.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 By the second decade of the 1800s, Anglo settlers occupied plantations along the St. Johns River, from the border with Georgia to Lake George 100 miles upstream. Spain began to lose control of the sparsely European-populated Florida amidst a tide of independence movements intent on shaking off the colonial yoke. Creek and Seminole Indians occupied the area from the Apalachicola River to the wet prairies and hammock islands of central Florida. These tribes, known to the Americans collectively as “Seminoles,” migrated into the region over the course of the 18th century and established settlements, tilled fields, and tended herds of cattle in the rich floodplains and grasslands that dominate the northern third of the Florida peninsula.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Violence near the Florida-Georgia border in late 1817 prompted an American invasion of Spanish Florida, commanded by Andrew Jackson. After bitter conflict that often pitted Americans against a collection of Native Americans and former slaves, Spain eventually agreed to transfer the territory to the U.S. in exchange for $5 million and other territorial concessions as part of the Adams-Onís Treaty.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 2 Planters from the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia entered Florida. However, the influx of settlers into the Florida territory was temporarily hauled in the mid-1830s by the outbreak of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). Free-blacks and escaped slaves also occupied the Seminole district; a situation that deeply troubled slave owners and constituted one of the major causes, beyond land dispossession, of the three Seminole Wars. Indeed, General Thomas Sidney Jesup, U.S. commander during the early stages of the Second Seminole War, labeled that conflict “a negro, not an Indian War.” As Florida became a state in 1845, settlement expanded into the former Indian lands and settlers reproduced the agricultural and social structures build on African slavery first introduced to north Florida in the 1820s.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Presidents, since at least Thomas Jefferson, had long discussed removal, but President Andrew Jackson took the most dramatic action. Jackson believed, “It [speedy removal] will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters.” Desires to remove American Indians from valuable farmland motivated state and federal governments to cease trying to assimilate Indians and instead plan for forced removal.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 1 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, seizing land east of the Mississippi and exchanging it for lands reserved in the west. This law followed the example of many existing state laws, notably ones passed in Georgia concerned the Cherokee nation. Many advocates of removal, including President Jackson, believed it would protect Indian communities from outside influences that jeopardized their chances of becoming “civilized” farmers. Jackson emphasized paternalism—the belief that the government was acting in the best interest of Native peoples— in his 1830 State of the Union Address. “It [removal] will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites…and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.”

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Among the various removals, the story of the Cherokee remains particularly brutal. In 1835, a portion of the Cherokee Nation signed the Treaty of New Echota, ceding lands in Georgia for five million dollars. Most of the tribe refused to adhere to the terms. In 1838, President Martin van Buren sent in the army to forcibly remove the Cherokee. Sixteen thousand began the journey, but harsh weather, poor planning, and difficult travel resulted in between 3,000-4,000 deaths on what became known as the Trail of Tears. While some tribes were able to resist removal or move to less desirable regions, many American Indians, whose homelands were east of the Mississippi, had been forcibly moved west by 1850. Over 60,000 Indians were forced west by the opening of the Civil War.

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 The discovery of gold in Georgia hastened the combined processes involved in dispossession. For example, state and federal governments pressured the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Cherokee nations to sign treaties and surrender land, despite many tribal members adopting some Euro-American ways, including intensified agriculture, slave ownership, and Christianity. Cherokee John Ridge pointed out the government’s hypocrisy. “You asked us to throw off the hunter and warrior state: We did so—you asked us to form a republican government: We did so. Adopting your own as our model. You asked us to cultivate the earth, and learn the mechanic arts. We did so. You asked us to learn to read. We did so. You asked us to cast away our idols and worship your god. We did so. Now you demand we cede to you our lands. That we will not do.”

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 Indian removal, while a disproportionately southern phenomenon, also took place to a lesser degree in northern lands. In the Northwest, Odawa and Ojibwe communities in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, resisted removal as many lived on land north of desirable farming land. Moreover, some Ojibwe and Odawa individuals purchased land independently. They formed successful alliances with missionaries to help advocate against removal, as well as some traders and merchants who depended on trade with Native peoples. Yet, Indian removal occurred in the North as well—the “Black Hawk War” in 1832, for instance, led to the removal of many Sauks to Kansas.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 Tribal nations also used the law in hopes of preventing the seizing of their lands. Most notable among these efforts was the Cherokee Nation’s attempt to prevent the state of Georgia from taking their lands. Beginning In 1828, the Cherokee defended themselves against Georgia’s laws by citing treaties signed with the United States that guaranteed the Cherokee nation both their land and independence. The Cherokee appealed to the Supreme Court against Georgia to prevent dispossession. The Court, while sympathizing with the Cherokees’ plight, ruled that it lacked jurisdiction to hear the case (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia – 1831). In an associated case, Worcester v. Georgia 1832, The Supreme Court ruled that Georgia laws did not apply within Cherokee territory. Regardless of these rulings, the state and federal governments forced Cherokee removal.

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 After the United States eliminated its European rivals from North America, American traders and settlers accelerated their violent push west. Despite the disaster of removal, tribal nations slowly rebuilt their cultures and in some cases even achieved prosperity in Indian Territory. Tribal nations west of the Mississippi blended traditional cultural practices, including common land systems, with western practices including constitutional governments, common school systems, and an elite slaveholding class.

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 1 Beginning in the late eighteenth-century, the Comanche rose to power in the Southern Plains region of what is now the Southwest United States. By quickly adapting to horse culture first introduced by the Spanish, the Comanche transitioned from a foraging economy into a mixed hunting and pastoral society, While the new Mexican nation-state, after 1821, claimed the region as part of the Northern Mexican frontier, they had little control. Instead, Comanches controlled the economy and geopolitics in the Southern Plains. Although politically organized as a loose confederacy, the Comanche shared social, political, legal, cultural, and religious practices that bound them together. This flexible political structure allowed them to dominate other Indian groups as well as Mexican and American settlers.

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 In the 1830s, the Comanches launched raids into northern Mexico, ending what had been an unprofitable but peaceful diplomatic relationship with Mexico. At the same time, they forged new trading relationships with Anglo-American traders in Texas. Throughout this period, the Comanche and several other independent Native groups, particularly the Kiowas, Apaches, and Navajo engaged in thousands of violent encounters with Northern Mexicans. Collectively, they comprised an ongoing war during the 1830s and 1840s as tribal nations vied for power and wealth. By the 1840s, Comanche power peaked with an empire that controlled a vast territory in the trans-Mississippi west known as Comancheria. By trading in Texas and raiding in Northern Mexico, the Comanche controlled the flow of commodities, including captives, livestock, and trade goods. They practiced a fluid system of captivity and captive trading, rather than a rigid chattel system. Comanches used captives for economic exploitation but also adopted captives into kinship networks. This allowed for the assimilation of diverse peoples in the region into the empire. The ongoing conflict in the region had sweeping consequences on both Mexican and American politics. The U.S.-Mexican War, beginning in 1846, can be seen as a culmination of this violence.

¶ 31

Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0

![]() “Map of the Plains Indians,” undated. Smithsonian Institute, http://americanhistory.si.edu/buffalo/files/pdf/TrackingTheBuffalo_Map_printable.pdf.

“Map of the Plains Indians,” undated. Smithsonian Institute, http://americanhistory.si.edu/buffalo/files/pdf/TrackingTheBuffalo_Map_printable.pdf.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 In the Great Basin region, Mexican Independence also escalated patterns of violence for the diverse tribal groups who inhabited the region. While on the periphery of the Spanish Empire, this region was nonetheless well integrated in the vast commercial trading network of the west. The new Mexican nation struggled to exert control on powerful Indian groups. Simultaneously, Anglo-American traders entered the region with their own imperial designs. New forms of violence spread into the homelands of the Paiutes and Western Shoshones as traders, settlers, and Mormon religious refugees committed daily acts of violence and officials and soldiers laid the groundwork for violent conquest. This expansion of the American state into the Great Basin region meant groups such as the Utes, Cheyenne and Arapahoe had to compete over land, resources, captives, and trade relations with Anglos-Americans. Eventually, white incursion and the envelopment of the west in ongoing Indian Wars resulted in the traumatic dispossession of land and struggle for subsistence for these groups.

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 The federal government did more than relocate Native Americans. Policies to “civilize” Indians coexisted along with forced removal. Thomas L. McKenney, superintendent of Indian trade from 1816 to 1822 and the Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1824 to 1830, served as the main architect of the “Civilization policy.” He asserted that American Indians were morally and intellectually equal to whites and advocated for the establishment of a national Indian school system as an extension of the factory system.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 Congress rejected McKenney’s plan but instead passed the Civilization Fund Act in 1819. This act offered a $10,000 annual annuity to be allocated towards societies that funded missionaries to establish schools among Indian tribes. However, providing schooling for Indians under the auspices of the Civilization program also allowed the federal government to further justify taking more land. Treaties, such as the 1820 Treaty of Doak’s Stand made with the Choctaw nation, often included land cessions as requirements for additional education provisions.

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 After the federal government removed the Five Tribes to Indian Territory during the 1830s, the Cherokees, Choctaws, and Chickasaws began to collaborate with missionaries to build school systems of their own. Leaders hoped that if the citizens of their nations were well educated, they could prevent further threats to their political sovereignty. In 1841, the Cherokee Nation opened a public school system that opened eighteen schools within two years. By 1852 it expanded to include twenty-one schools with a national enrollment of 1,100 pupils. Many of the students educated in these tribally controlled schools later served their nations as teachers, lawyers, physicians, bureaucrats, and politicians.

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

IV. Life and Culture in the West

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 Western settlers usually migrated as families and settled along navigable and drinkable rivers. Settlements often coalesced around local traditions, especially religion, carried from eastern settlements. These shared understandings encouraged a strong sense of cooperation among western settlers that helped forge some of the early communities on the frontier.

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 Before the Mexican War, the West for most Americans still referred to the fertile area between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River with a slight amount of overspill beyond its banks. With soil exhaustion and land competition increasing in the East, most early western migrants sought a greater measure of stability and self-sufficiency by engaging in small scale farming. Boosters of these new agricultural areas along with the U.S. government encouraged perceptions of the west as a land of hard-built opportunity that promised personal and national bounty.

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Women migrants bore the unique double burden of travel while conforming to restrictive gender norms. Societal standards such as “the cult of true womanhood,” which emphasized piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness as the key virtues of women, and the “separate spheres,” which focused on the role of the woman in the home, often accompanied men and women as they traveled west to begin their new life.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 While many societal standards continued just as they had in the established communities people left behind, there often existed an openness of frontier society that resulted in more power for women. Husbands needed partners in setting up a homestead and working in the field to provide food for the family. Suitable wives were in short supply, enabling some to negotiate more power in their households, although typically on an informal level.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 Economic busts constantly threatened western farmers. As the economy worsened after the panic of 1819, farmers were unable to pay their loans due to falling prices and overfarming. The dream of subsistence and stability abruptly ended as many migrants lost their land and moved farther west. The federal government consistently sought to increase access to land in the west, including by lowering the amount of land required for purchase. Smaller lots made it easier for more farmers to clear land and begin farming faster.

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 The availability of affordable loans fueled the growth of land speculation. The amount of money in circulation eclipsed more than $100 million dollars by 1817, much of it being lent by state banks. While the federal government, through the Second Bank of the United States (rechartered in 1816) took a more conservative approach to lending, state banks – particularly those of the frontier states – offered loans more freely to new migrants looking to buy land. Just as cash cropping gave western migrant communities hopes of quickly striking it rich, land speculation promised the same outcome for state bank investors.

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 Predictably, the booms in speculation and agriculture busted together in the Panic of 1819. Farmers failed in the cash crop market and could not repay their loans. The mortgages of these western farmers were supposed to have guaranteed the stability of the banks. However, as state banks grew in economic power, they printed far more notes than they had cash or gold to back the notes. The speculation in land fueled a speculation in banknotes, both of which fell together. These banks, in their last acts of desperation demanded immediate mortgage payment in specie from farmers, payments that farmers simply could not make. Making matters worse for farmers and exacerbating the effects of the panic was overproduction and foreign competition flooding the markets. Even though profitability and land purchases picked up by the mid-1820s, the rate of growth greatly slowed and land prices never returned to their pre-crash highs.

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 In response, Congress embraced higher tariffs in 1824 and 1828 that sought to protect American agriculture from foreign competition. Many Americans looked upon banking more skeptically, particularly the Bank of the United States. Andrew Jackson made destruction of the bank a key political issue and succeeded in taking government deposits out of the bank and circulating them to state banks. Unfortunately, this policy had a disastrous effect as state banks used this money to make more speculatory loans. This recreated the pre-1819 atmosphere and created the Crash of 1837. However, these deposits also helped state banks fuel transportation improvements that proved helpful for farmers and consumers.

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 More than anything else, new road and canals created economic growth in the 1820s and 1830s. Canal improvements expanded in the east, while road building prevailed in the west. Congress continued to allocate funds for internal improvements. Federal money pushed the National Road, begun in 1811, farther west every year. Laborters needs to construct these improvements increased employment opportunities and encouraged non-farmers to move the West. However, roads were expensive to build and maintain and some Americans strongly opposed spending money on these projects.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 Steamboats first came into limited usage in the United States prior to 1810. However, their importance and number grew quickly throughout the 1810s and into the 1820s. Steam power augmented the already widespread use of slow moving human-rowed or mule-pulled flatboats and keelboats already parading down various waterways throughout the East. As water trade and travel grew in popularity, local and state governments along with the federal government all allocated funds for the improvement and connecting of rivers and streams.

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 Steamboats offered greater reliability, power, speed, and versatility. As a result of the steamboat’s popularity and profitability, hundreds of miles of new canals popped up throughout the eastern landscape, and to a lesser degree in the West (although in smaller numbers and length). The most notable of these early projects was the Erie Canal. That project, completed in 1825, linked the Great Lakes to New York City. The profitability of the canal helped New York outpace its east coast rivals to become the center for commercial import and export in the United States.

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 Steamboats and canals, with roads playing their part as well, undoubtedly revolutionized travel and economics in the early United States. Population grew in canal and river towns. Trade, fueled by a growing need for raw materials of construction and foodstuffs for growing towns, increased just as fast. The needs of families and communities, increasingly dependent on construction and commercial life for their livelihoods, turned to manufactured products and distantly-produced food sold in the marketplace in order to feed their consumptive needs.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 Railroads, although hampered by some of the obstacles of road building, made the labor and investment costs worth the risk by reducing transportation time in a way roads could not. Early railroads like the Baltimore and Ohio line sought to tie those cities to lucrative western trades routes in the hopes of displacing New York as a central port of trade. Railroads encouraged the rapid growth of towns and cities all along the routes through the encouragement of boosterism in search of speculative profits. The West benefited greatly from the growth of railroads. Not only did rail lines promise to move commerce faster, but the rails also encouraged the spreading of towns farther away from their traditional locations along waterways. The filling in of lands previously left to tribal nations increased conflict throughout the West, but these conflicts were seen as acceptable to white settlers looking to expand farmlands and profits.

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 Eastern and western towns that lacked navigable waterway connections suddenly had new outlets to the markets that augured for greater profit, refining of culture, and a sharing of national impulses. Railroads and canals carried not only cargo but new settlers and new political issues along their paths. However, technological limitations, constant need for repairs, conflicts with native Americans, political disagreements over funding and routes, and the challenge of understanding and adapting to new technology all hampered railroading and kept canals and steamboats as integral parts of the transportation system. However, this early period of construction and use of railroads set the stage for their rapid expansion in the decades after the Civil War.

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0

V. Slavery in the West

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 Technology, transportation, and the market came together most notably in the rise of cotton production in the West and the movement of slavery to support the crop’s cultivation. Technological changes in the planting and harvesting of cotton as well as the revolutions in economics and transportation encouraged robust movement of white settlers and black slaves to the West. This process, referred to by historians as ‘the second slavery, encouraged farmers, speculators, and boosters importation of the traditional American system of plantation slavery to the West.

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 Planters of the Old South, looking to profit from their excess stocks of slaves, contracted with large northern slave-trading firms with branches in large gulf coast cities like Natchez and New Orleans. These firms’ speculators bought their human cargo in New Orleans and traveled with the purchased slavery to plantations throughout the southwest. “Alabama fever” swept the fertile Mississippi valley lands. The explosion of an exploitable cash crop like cotton was the foundation of the entire system. High slave and cotton demand coupled with improved transportation and plentiful land all combined to drive land and slave prices to new heights. The entire U.S. cotton output double in the decade after the War of 1812, with 50% of that total coming from Alabama and Mississippi. This spurred the Second Middle Passage that took slaves from the Upper South to the expanding plantation economies of the Deep South and Texas. By 1860, over two million slaves, 55 percent of the entire U.S. slave population, lived in states that came into existence after the founding of the country.

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 By that same year, cotton and the speculative profits gained from the associated transportation and slave-trade apparatuses, claimed two-thirds of the entire U.S. economy; a reality that produced yet another speculative bubble in 1837 that burst with even more force this time.

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 The discipline regime on western plantations added to the harshness of treatment and mental anguish of a population already ripped from their community and familial ties in the forced movement from the Old South to the West. The needs of the sugar and cotton industries fell upon the backs of slaves as smaller farmers and larger plantations owners pushed their slaves harder and harder for productivity increases. Despite the terror and hardships all around them, enslaved men and women formed families and fostered what sense of community they could while under constant threat from forced migration.

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 Capitalism and the mobility of slave property defined the domestic trade of the second slavery in the antebellum period. Much of the economic growth of the United State during the period was due in large part to the power to own labor property in human beings. This right to property, defended by slaveowners and affirmed in the Dred Scott decision, was not just a philosophical position but was a defense of owners most valuable asset. A labor force that could be moved and exhausted enabled planters to increase production in response to increasing demand.

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 Technological improvements in production, refining, and transportation allowed the movement of slave property and staple products on a hitherto unforeseen scale. These second slavery staple commodities were the building blocks of domestic and foreign industrial production. The flexibility and adaptability shown by slaveowners translated into other areas of American society such as new business practices. This entrepreneurial spirit, so lauded in the American DNA and chiefly extolled among the white settlers in the West, rested on the developments and demands placed upon the system of slavery exported west of the Mississippi in the antebellum period.

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 The expansion of slavery did not take place without much debate and controversy. Slavery and western expansion became the national crisis by the 1840s. The Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854 opened slavery to popular vote in the plains territories. The rush to populate Kansas Territory by abolitionists and pro-slavery supporters turned westward migration into a political battle over the future of the United States; as a result Bleeding Kansas, a guerrilla war in that territory lasted over a decade. Migrations westward precipitated the Civil War by forcing the nation to decide whether it would allow slavery to expand and the rights to property of slaveholders protected as inviolate throughout the country. While many sought new opportunities in the West, many others suffered from forced migration that uprooted whole communities and destroyed lives.

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0

VI. Texas and Mexico and America

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0 Before the debate over slavery in the West reached a national level, the issue became one of the prime forces behind the Texas revolution and that republic’s annexation to the United States. After gaining its independence from Spain in 1821 Mexico hoped to attract new settlers to its northern areas in order to create a buffer between it and the expanding western populations of the United States. New immigrants, mostly from the southern United States, poured into Texas. Over the next twenty-five years, concerns over growing Anglo influence and possible American designs on Texas produced great friction between Mexican and American populations. In 1829, Mexico, hoping to quell anger and immigration, outlawed slavery and required all new immigrants to convert to Catholicism. American immigrants, eager to expand their agricultural fortunes, largely ignored these requirements. In response, Mexican authorities closed their territory to any new immigration in 1830- a prohibition roundly elided by Americans who often squatted on public lands.

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 In 1834, an internal conflict between federalists and centralists in the Mexican government led to the political ascendency of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. Santa Anna, Governing as a dictator, repudiated the federalist Constitution of 1824, pursued a policy of authoritarian central control, and crushed several revolts throughout Mexico prompted by his coup. Texian settlers opposed Santa Anna’s centralizing policies and met in November after issued a statement of purpose that emphasized their commitment to the Constitution of 1824 and declared Texas to be a separate state within Mexico. After angry Mexican rejection of the offer, Texian leaders soon abandoned their fight for the Constitution of 1824 and declared independence on March 2, 1836. The Texas Revolution of 1835-1836 was a successful secessionist movement in the northern district of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas that resulted in an independent Republic of Texas.

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0 At the Alamo and Goliad, Santa Anna crushed smaller rebel forces and massacred hundreds of Texian prisoners. The Mexican army pursued the retreating Texian army deep into East Texas, spurring a mass panic and evacuation by Anglo civilians known as the “Runaway Scrape.” Santa Anna consistently failed to make adequate defensive preparations and was eventually caught by surprise on April 21, 1836 by an attack from the outnumbered Texian army led by Sam Houston. The battle of San Jacinto lasted only eighteen minutes and resulted in a decisive victory for the Texians, who retaliated for previous Mexican atrocities by continuing to kill fleeing and surrendering Mexican troops for hours after the initial assault. Santa Anna was captured in the aftermath and compelled to sign the Treaty of Velasco on May 14, 1836, by which he agreed to withdraw his army from Texas and acknowledged Texas independence. Although a new Mexican government never recognized the Republic of Texas, the United States and several other nations gave the new country diplomatic recognition.

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 Texas annexation had remained a political landmine since the Republic declared independence from Mexico in 1836. American politicians feared that adding Texas to the Union would provoke a war with Mexico and re-ignite sectional tensions by throwing off the balance between free and slave states. However, after his expulsion from the Whig party, President John Tyler saw Texas statehood as the key to saving his political career. In 1842, he began work on opening annexation to national debate. Harnessing public outcry over the issue, Democrat James K. Polk rose from virtual obscurity to win the presidential election of 1844. Polk and his party campaigned on promises of westward expansion, with eyes toward Texas, Oregon, and California. In the final days of his presidency, Tyler at last extended an official offer to Texas on March 3, 1845. The republic accepted on July 4, becoming the twenty-eighth state.

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0 Mexico denounced annexation as “an act of aggression, the most unjust which can be found recorded in the annals of modern history.” However, perhaps the most important point of conflict between Mexico and the United States was a narrow strip of land to which both countries now laid claim. While Mexico drew the southwestern border of Texas at the Nueces River, Texans had claimed that the border lay roughly 150 miles further west at the Rio Grande. Neither claim was realistic. The sparsely populated area, known as the Nueces strip, was in fact controlled by independent Indian tribes.

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0 In November of 1845, President Polk secretly dispatched John Slidell to Mexico City in order to attempt a purchase of the Nueces strip along with large sections of New Mexico and California. The mission was an empty gesture, designed largely to pacify those in Washington who insisted on diplomacy before war. Predictably, officials in Mexico City refused to receive Slidell. Earlier that year, Polk had also sent a 4,000 man army under General Zachary Taylor to Corpus Christi, Texas; just northeast of the Nueces River. Upon word of Slidell’s refusal in January 1846, Polk ordered Taylor to cross into the disputed territory. The President hoped that this show of force would push the lands of California onto the bargaining table as well. He badly misread the situation. After losing Texas, the Mexican public strongly opposed surrendering any more ground to U.S. expansionism. Popular opinion left the shaky government in Mexico City without room to negotiate. On April 24, Mexican cavalrymen attacked a detachment of Taylor’s troops just north of the Rio Grande, killing eleven U.S. soldiers.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0 It took two weeks for the news to reach Washington. Polk sent a message to Congress on May 11. “We have tried every effort at reconciliation…but now, after reiterated menaces, Mexico…has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil.” However, with fighting already underway, a vote against war became a vote against supporting American soldiers under fire. Congress passed a declaration of war on May 13. Only a few members of both parties, notably John Quincy Adams and John C. Calhoun, voted against the measure. However, opposition to “Mr. Polk’s War” soon grew widespread. Upon declaring war in 1846, Congress issued a call for 50,000 volunteer soldiers. Spurred by promises of adventure and conquest abroad, thousands of eager men flocked to assembly points across the country.

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0 In the early fall of 1846, the U.S. Army invaded Mexico on multiple fronts and within a year’s time General Winfield Scott’s men took control of Mexico City. However, the city’s fall did not bring an end to the war. Scott’s men occupied Mexico’s capital for over four months while the two countries negotiated. In the United States, the war had been controversial from the beginning. Embedded journalists sent back detailed reports from the front lines, and a divided press spun and debated the news viciously. Volunteers found that the real experience of war was not as they expected. Disease killed seven times as many American soldiers as combat did. Harsh discipline, conflict within the ranks, and violent clashes with civilians led soldiers to desert in huge numbers. Peace finally came on February 2, 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

¶ 68

Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0

“General Scott’s entrance into Mexico.” Lithograph. 1851. Originally published in George Wilkins Kendall & Carl Nebel, The War between the United States and Mexico Illustrated, Embracing Pictorial Drawings of all the Principal Conflicts (New York: D. Appleton), 1851. Wikimedia Commons

“General Scott’s entrance into Mexico.” Lithograph. 1851. Originally published in George Wilkins Kendall & Carl Nebel, The War between the United States and Mexico Illustrated, Embracing Pictorial Drawings of all the Principal Conflicts (New York: D. Appleton), 1851. Wikimedia Commons

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0 The new American Southwest attracted a diverse group of entrepreneurs and settlers to the commercial towns of New Mexico, the fertile lands of eastern Texas, and the famed gold deposits of California and the Rocky Mountain chains. This postwar migration built upon migration to the region dating back to the 1820s, when the lucrative Santa Fe trade enticed merchants to New Mexico and generous land grant opportunities brought numerous settlers to Texas. The Gadsden Purchase of 1854 further added to American gains north of Mexico.

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0 The U.S.-Mexican War had an enormous impact on both countries. The American victory helped set the United States on the path to becoming a world power, elevated Zachary Taylor to the presidency, and served as a training ground for many of the Civil War’s future commanders. Most significantly, however, Mexico lost roughly half of its territory. Yet, the United States’ victory was not without danger. Ralph Waldo Emerson predicted ominously at the beginning of the war that, “Mexico will poison us.” Indeed, the conflict over whether or not to extend slavery into the newly won territory pushed the nation ever closer to disunion and civil war.

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0

VII. Manifest Destiny and the Gold Rush

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0 California, belonging to Mexico prior to the war, was at least three arduous months travel from the nearest American settlements. While missionaries made the trip more frequently, there was some sparse settlement in the Sacramento valley. The fertile farmland of Oregon, like the black dirt lands of the Mississippi valley, attracted more settlers than California.

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 Exacerbating concerns was the presence of often over-dramatized stories of Indian attack that filled migrants with a sense of foreboding, although the majority of settlers encouraged nonviolence and often no Indians at all. The slow progress, disease, human and oxen starvation, poor trails, terrible geographic preparations, lack of guidebooks, threatening wildlife, vagaries of weather, and general confusion were all more formidable and regular challenges than Indian attack. Despite the harshness of the journey, by 1848 there were approximated 20,000 Americans living west of the Rockies, with about three-fourths of that number in Oregon.

¶ 74

Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0

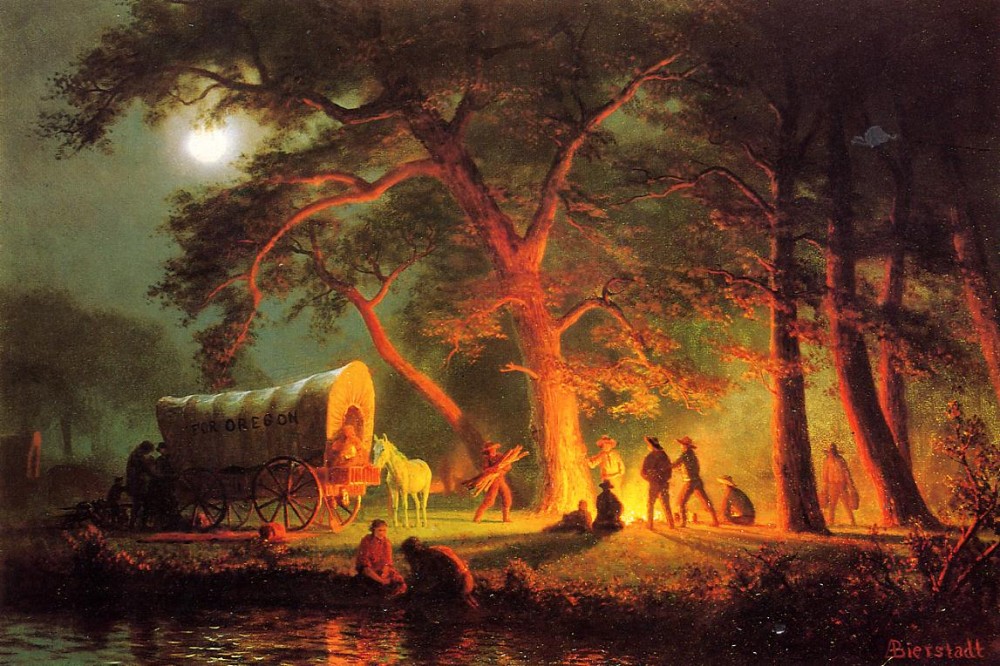

The great environmental and economic potential of the Oregon Territory led many to pack up their families and head west along the Oregon Trail. The Trail represented the hopes of many for a better life, represented and reinforced by images like Bierstadt’s idealistic Oregon Trail. Albert Bierstadt, Oregon Trail (Campfire), 1863. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bierstadt_Albert_Oregon_Trail.jpg.

The great environmental and economic potential of the Oregon Territory led many to pack up their families and head west along the Oregon Trail. The Trail represented the hopes of many for a better life, represented and reinforced by images like Bierstadt’s idealistic Oregon Trail. Albert Bierstadt, Oregon Trail (Campfire), 1863. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bierstadt_Albert_Oregon_Trail.jpg.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0 The lure and imagination of the West lured many migrants to the far west. However, those with the adventuring spirit and stomach were modest. Many who moved sought the reflection of what they believed themselves to be in the great untamed lands of the West. The romantic vision of life west of the Mississippi attracted a certain breed of Americans. The rugged individualism and martial prowess of the West and the Mexican war was the first spark that drew a new breed different than the modest agricultural communities of the near-west.

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 If the great draw of the West stood as manifest destiny’s kindling then the discovery of gold in California was the spark the set that fire ablaze. The strongest driving forces of Manifest Destiny lay in the somewhat coordinated movement of settlers via trails (slave-based, subsistence agriculture, and religious), the military (War with Mexico and American Indians, filibustering adventures), and political focus (the expansion of slavery, Compromise of 1850) toward the western territory added to the United States. Undoubtedly, while the vast majority of those leaving the Eastern seaboard and old Mississippi valley frontier via the wagon trails sought land ownership, the lure of getting rich quick drew a not unsizable portion of the migration’s primarily younger single male participants (with some women) to gold towns throughout the West. These core constituencies of adventures and fortune-seekers then served as magnets for the arrival of corresponding providers of services associated with the gold rush. The rapid growth of towns and cities throughout the West, notably San Francisco whose population grew from about 500 in 1848 to almost 50,000 by 1853, and the seemingly endless possibility for individual success in all matters of pursuit put a positive economic spin on the tenets of manifest destiny. Yet, the lawlessness, predictable failure of most fortune seekers, conflicts with native populations of the area – including Mexican, Spanish, American Indian, Chinese, and Japanese populations – and the explosion of the slavery question all demonstrated the downside of Manifest Destiny’s promise. The gold rush sped up the already quickening political march to the Pacific.

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 0 On January 24, 1848 James W. Marshall, a contractor hired by John Sutter, discovered gold on Sutter’s sawmill land in the Sacramento valley area of the then territory of California. The agitation of the territory’s relatively small American population, much like Texas before it, attracted substantial U.S. military effort in aid of some American forces already there at the onset of the Mexican war. Encouragement of westward migration was as much an individual economic imperative as it was a national defense necessity. The discovery of gold did much to solve at least one of those issues as the integration of the quickly populated state California, and with it the vital port of San Francisco, augmented American strength and national economic grounding. Throughout the 1850s, Californians beseeched Congress for a transcontinental railroad to provide service for both passengers and goods from the Midwest and the East Coast. The potential economic benefits for communities along proposed railroads made the debate over the railroad’s route rancorous and overlapped on top of growing dissent over the slavery issue. For their part, the economic boom ushered in by the gold rush allowed the state government of California to begin work on a state rail system in the Sacramento Valley in 1854.

¶ 78 Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0 The great influx of people and the great diversity on display, encased in a combative and aggrandizing atmosphere of individualistic pursuit of fortune, produced all sorts of antagonisms. Linguistic, cultural, economic, and racial conflict roiled both urban and rural areas. By the end of the 1850s, Chinese and Mexican immigrants made up 1/5th of the mining population in California mining towns. The competition for land, resources, and riches furthered individual and collective abuses particularly against American Indians and the older Mexican communities and missions established before statehood. California’s towns, as well as those dotting the landscape throughout the West, struggled to balance security with economic development and the protection of civil rights and liberties.

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0

VIII. The Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny.

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0 Expansion of influence and territory off the continent became an important corollary to westward expansion. One of the main goals of the U.S. government was the prevention of outside involvement of European countries in the affairs of the western hemisphere. American policymakers sought an outlet for the domestic assertions of manifest destiny in the nation’s early foreign policy decisions of the antebellum period.

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 1 As Secretary of State for President James Monroe, John Quincy Adams (pictured) held the responsibility for the satisfactory resolution of ongoing border disputes in different areas of North America between the United States, England, Spain, and Russia. Adams was a proponent of both the concept of continentalism and an American influence in hemispheric events. Adams’ comprehensive view of American policy aims was put into clearest practice in the Monroe Doctrine, which he had great influence in crafting.

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0 Increasingly aggressive incursions from the Russians in the Northwest, ongoing border disputes with the British in Canada, the remote possibility of Spanish reconquest of South America, and British abolitionism in their Caribbean colonies all forced a U.S. response to the threats encircling the country. However, despite the philosophical confidence present in the Monroe administration’s decree, the reality of limited military power kept the Monroe Doctrine as an aspirational assertion that many in the administration and the country believed the United States would grow into as it matured. Secretary of State Adams acknowledged the American need for a robust foreign policy that simultaneously protected and encouraged the growing and increasingly dynamic capitalist orientation of the country in a speech before the U.S. House of Representatives on July 4th, 1821.

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0 America…in the lapse of nearly half a century, without a single exception, respected the independence of other nations while asserting and maintaining her own…She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own. She will commend the general cause by the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example. She well knows that by once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom. The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force. The frontlet on her brows would no longer beam with the ineffable splendor of freedom and independence; but in its stead would soon be substituted an imperial diadem, flashing in false and tarnished lustre the murky radiance of dominion and power. She might become the dictatress of the world; she would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit. . . . Her glory is not dominion, but liberty. Her march is the march of the mind. She has a spear and a shield: but the motto upon her shield is, Freedom, Independence, Peace. This has been her Declaration: this has been, as far as her necessary intercourse with the rest of mankind would permit, her practice. John Quincy Adams

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0 However, Adams’ great fear was not territorial loss. He had no doubt that Russian and British interests in North America could be arrested. Adams held no reason to antagonize the Russians with grand pronouncements nor was he generally called upon to do so. He enjoyed a good relationship with the Russian Ambassador and stewarded through Congress most-favored trade status for the Russians in 1824. Rather, Adams worried gravely about the ability of the United States to compete commercially with the British in Latin America and the Caribbean. This concern deepened with the valid concern that America’s chief Latin American trading partner, Cuba, dangled perilously close to outstretched British claws. The Cabinet debates surrounding establishment of the Monroe Doctrine, the international diplomacy undertaken by Adams and his underlings, and geopolitical events in the Caribbean focused attention on that part of the world as key to the future defense of U.S. military and commercial interests with the main threat to those interests being the British. Expansion of economic opportunity and protection of American society and markets from foreign pressures became the overriding goals of U.S. foreign policy.

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0 Bitter disagreements over the expansion of slavery into what became the Mexican Cession territory began even before the Mexican war ended. Many Northern business and Southern slaveowners supported the idea of expansion of American power and slavery into the Caribbean as a useful alternative to continental expansion since slavery already existed in these areas. While some were critical of these attempts, seeing them as evidence of a growing slave-power conspiracy, many supported these extra-legal attempts at expansion. Filibustering, as it was called, was privately financed schemes of varying degrees of operational reality directed at capturing and occupying foreign territory without the approval of the U.S. government.

¶ 86 Leave a comment on paragraph 86 1 Filibustering adventures took greatest hold in the imagination of Americans as they looked toward Cuba with particular interest. Fears of racialized revolution in Cuba (as in Haiti before it) as well as the presence of an aggressive British abolitionary influence in the Caribbean energized the movement to annex Cuba and encouraged filibustering activities as expedient alternatives to lethargic official negotiations. Despite filibustering’s seemingly chaotic planning and destabilizing repercussions, those intellectually and economically guiding the effort saw in their efforts a willing and receptive Cuban population and an agreeable American business class. In Cuba, manifest destiny for the first time sought territory off the continent and hoped to put a unique spin on the story of success in Mexico. Yet, the annexation of Cuba, despite great popularity and some military attempts led by Narciso Lopez (pictured), a Cuban dissident, never succeeded.

¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0 Regardless of that disappointment planning and action against other areas took place. Most notable among these efforts was William Walker’s momentarily successful filibustering against Nicaragua. Walker, who was a long-time filibusterer, launched several expeditions in Mexico and Central America and achieved success in establishing his rule and slavery on the Nicaraguan coast before eventually being executed, with British encouragement, in Honduras. Although these mission enjoyed neither the support of the law or the U.S. government, wealthy Americans financed various filibusters and less-wealthy adventurers were all to happy to sign up. Filibustering enjoyed its brief popularity into the late 1850s, at which point slavery and concerns over session came to the fore. By the opening of the Civil War most saw these attempts as simply territorial theft and muscular articulations of individual desires toward profit and dominance. Caribbean expansion, now predicated on the reinvigoration of slavery through filibustering, seemed anathema to the American democratic disposition.

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 2 One of the last pieces of manifest destiny’s collapse was the economic fracturing of the regions of the United States. The national economic market steadily weakened as a unifying entity after 1857 when the South finally received some tangible demonstration of the superiority of their economic project. They emerged from the Panic of 1857 with the sense that the North needed Southern commerce more than the South needed Northern industry. The South embraced this evidence and the resultant increase in its confidence as they suffered under the presumption that Northern dominance might never relent. The confidence gained through lucrative business relations with world markets, the diversification of the Southern manufacturing base, the relatively light toll taken by the Panic of 1857, the possibility of Cuban annexation, the dominance of presidential elections in the 1850s, and the political capitulation of Northern interests in the tariff debate of 1858 all led the South toward a belief in the political possibility of secession and the likelihood of success

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0 Throughout the antebellum period slavery continuously expanded onto new ground, embracing new crops, and new machinery. The planter class throughout the United States, the Caribbean, and South America exerted a political and economic dominance in rising world markets and their national political cultures that made the continued existence of slavery the foundation of their power. Yet, profits gained in the sugar, coffee, and cotton areas also depended on a complex economic and industrial partnership between non-slave owning business/production entities and slaveholding agriculturalists. The entire undertaking of the Atlantic economy fueled American growth and drove the confidence and economic funding required for the completion of manifest destiny’s expansion. Workers and financiers, slaves and settlers, planters and industrialists all produced, willingly or forced, the economic juggernaut that, while encouraging American expansion, also became a part of its undoing.

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 0

IX. Conclusion

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0 The debates over expansion, economics, diplomacy, and manifest destiny in the antebellum decades exposed some of the weaknesses of the American system. Despite a perceived American national chauvinism in the actions of the Native American removal, the Mexican war, and filibustering, the bombast of the period bellied a growing malaise among citizens in a society struggling with understanding its past and dealing with its current concerns. Manifest destiny attempted to make a virtue of America’s lack of originating myth as a basis for nationhood. To locate such origins, John O’Sullivan and other destinarians lifted that basis off of a biological or territorial imperative, common among European definitions of nationalism, and placed it onto political culture. The United States was the embodiment of the democratic ideal. Democracy had to be timeless, boundless, and portable. New methods of transportation and communication, the rapidity of the railroad and the telegraph, the rise of the international market economy, and the growth of the American frontier provided shared cultural platforms that helped Americans think across local identities and reaffirm their national character.

Typo: should be “was temporarily halted“

Good. Jesup’s quote is very important. During the Second Seminole War, Florida became the most militarized territory in U.S. history. The concern was not over Indian removal as much as fear that Indian resistance would attract more enslaved Blacks to join and might result in a general slave uprising. One white citizen wrote home to her family New Hampshire that she feared “the horrors of San Domingo” could be repeated in Florida.