11. The Old South

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

Eastman Johnson, “Negro Life at the South,” 1859

Eastman Johnson, “Negro Life at the South,” 1859

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 *Click here to view the current published draft of this chapter*

I. Introduction

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 1 Scarlet O’Hara, dazzling in a sumptuous gown, stands in front of her grand mansion while dashing young men seek to court her. The romanticized Old South found in Gone With the Wind contrasts starkly with the 2013 Oscar winner, Twelve Years a Slave. In this picture, viewers saw enslaved men, women, and children living under brutal exploitation. Scholars agree that this depiction is more akin to reality than Scarlet O’Hara ever was. But this too is not the whole picture. Moviegoers rarely see the vibrant culture African Americans built under slavery, or the poor whites that supported slavery even though they did not own slaves, or the diverse southern cities where Italians and Irishmen labored alongside free and enslaved black Americans. The Old South is too complex to represent on one big screen.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 The economy and society of the Old South was rooted in cotton and slavery, producing a social structure and culture unique to the region. Slavery governed relationships between southerners in ways that could be violent or subtle. While only a minority of southerners owned slaves, the institution nonetheless shaped the region. The expansion of slavery and the development of the cotton economy were possible only through federal and local policies of removal, devastating Native American communities in the process. Across the Old South, interactions between white settlers, black slaves, Native Americans, and immigrants from Europe and the Caribbean helped to create a rich and unique culture. Local identity mattered a great deal to these people, but southerners also maintained important ties with the wider world through trade and migration. Such complexity make apparent why Hollywood continues to visit the Old South. The drama, tragedy, and even comedy in the southern past have much to teach us about our nation and ourselves.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

II. Plantation Economy and Politics

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 In 1827, a visitor to Charleston, South Carolina, took notice of “mountains of Cotton” piled on the wharf as he stepped off his boat. As he ambled around the city, it seemed that everyone spoke only of “Cotton! Cotton!! Cotton!!!” His trip through Georgia, Alabama and Louisiana revealed numerous cotton fields and slave owners forcing large gangs of slaves to walk towards potential cotton plantations along the Mississippi River. Upon his arrival in Nashville, he encountered yet more cotton piled high on wagons, steamboats, flatboats, and schooners awaiting transportation to New Orleans. At the conclusion of his trip, the traveler joked that he had been “seeing, hearing, and dreaming of nothing but cotton.”

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 While the traveler’s observations reflected the importance of the fleecy staple to the South’s economy and society in 1827, the United States produced relatively little of the staple crop in the nation’s early years. In 1793, southerners produced only about 10,000 bales of cotton. A combination of factors, including an improved cotton gin, better machinery to spin the fiber into thread, and the ability of steamboats to haul thousands of cotton bales (each of which was about the size and weight of a modern refrigerator), unleashed the crop’s potential. By the time Abraham Lincoln was elected president, southerners had sold nearly 4.5 million bales and cotton made up 60 percent of all American exports.

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0

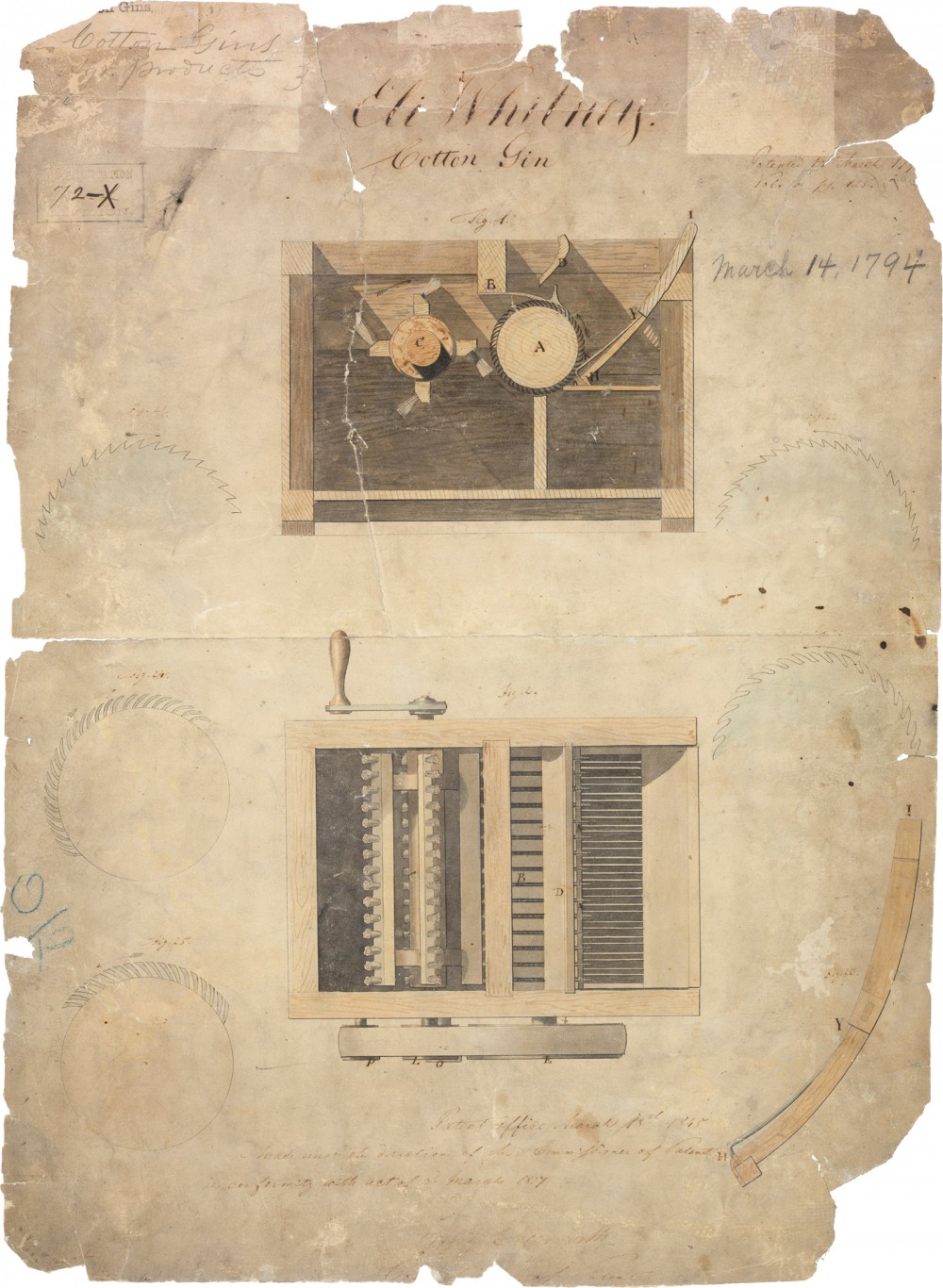

Eli Whitney’s mechanical cotton gin revolutionized cotton production and expanded and strengthened slavery throughout the South. Eli Whitney’s Patent for the Cotton gin, March 14, 1794; Records of the Patent and Trademark Office; Record Group 241. Wikimedia.

Eli Whitney’s mechanical cotton gin revolutionized cotton production and expanded and strengthened slavery throughout the South. Eli Whitney’s Patent for the Cotton gin, March 14, 1794; Records of the Patent and Trademark Office; Record Group 241. Wikimedia.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

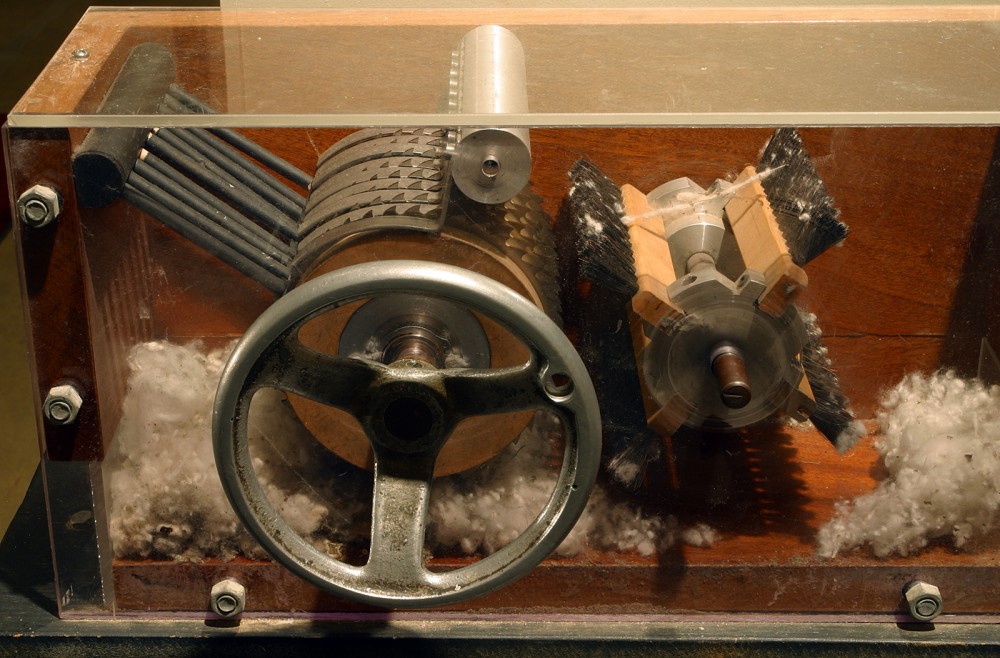

A 19th-century cotton gin on display at the Eli Whitney Museum. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cotton_gin_EWM_2007.jpg.

A 19th-century cotton gin on display at the Eli Whitney Museum. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cotton_gin_EWM_2007.jpg.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 As cotton production soared, it fueled demand for the fertile lands stretching from northern Georgia westward to the Mississippi River termed the “black belt.” The “black belt” described both the color of the rich soil and the physical appearance of the slaves who worked the land. Cotton helped ignite industrial revolutions in England and the United States, provided profits to northern banks and insurance companies, nourished international trade networks, and brought affluence to southern planters. Like oil today, cotton was the world’s most valuable commodity.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Efforts to spread cotton culture to Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida wreaked untold havoc on Native Americans landholders. Whites pressured the federal government to drive out the Native Americans. The United States army forcibly removed and exiled over 60,000 Choctaws, Creeks, Chickasaws, Seminoles, and Cherokees to “Indian Territory” in Oklahoma. The spread of the cotton kingdom also fueled expansionist desires. White southerners settled lands in Mexico, which would later become Texas, hoping to spread cotton cultivation as far as present-day Arizona and New Mexico. Southerners also pressured the federal government to acquire land in the Caribbean so that slavery and cotton production could flourish there as well.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

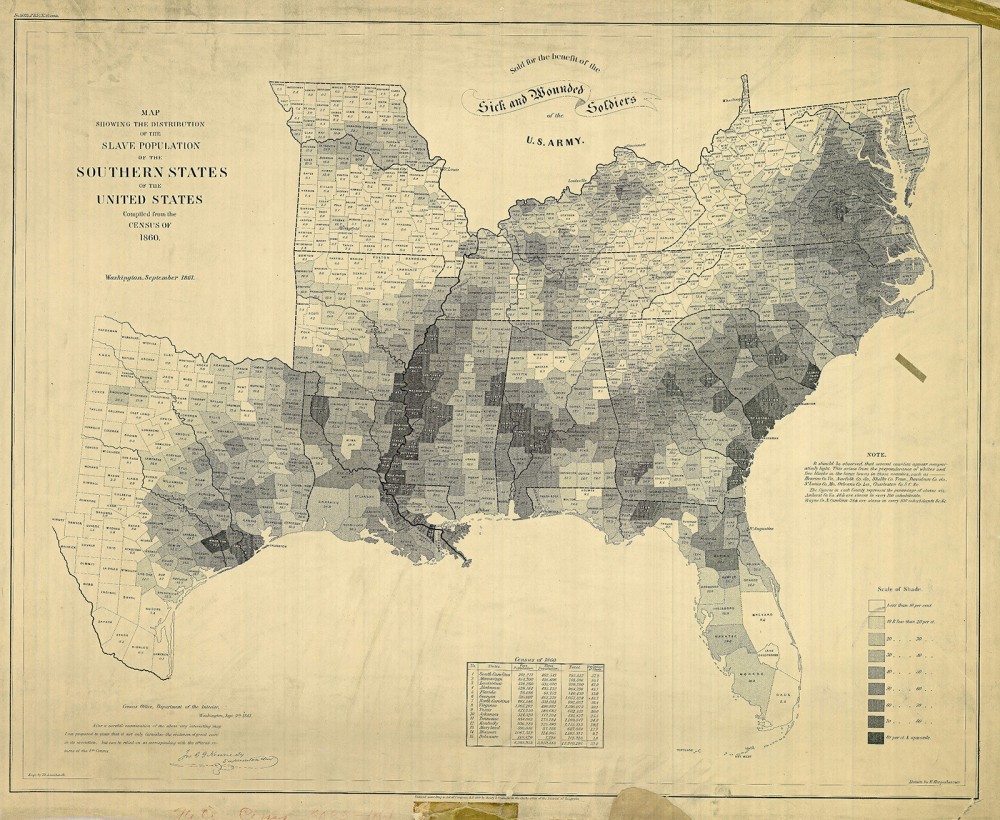

This map, published by the US Coast Guard, shows the percentage of slaves in the population in each county of the slave-holding states in 1860. The highest percentages lie along the Mississippi River, in the “Black Belt” of Alabama, and coastal South Carolina, all of which were centers of agricultural production (cotton and rice) in the United States.E. Hergesheimer (cartographer), Th. Leonhardt (engraver), Map Showing the Distribution of the Slave Population of the Southern States of the United States Compiled from the Census of 1860, c. 1861. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SlavePopulationUS1860.jpg.

This map, published by the US Coast Guard, shows the percentage of slaves in the population in each county of the slave-holding states in 1860. The highest percentages lie along the Mississippi River, in the “Black Belt” of Alabama, and coastal South Carolina, all of which were centers of agricultural production (cotton and rice) in the United States.E. Hergesheimer (cartographer), Th. Leonhardt (engraver), Map Showing the Distribution of the Slave Population of the Southern States of the United States Compiled from the Census of 1860, c. 1861. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SlavePopulationUS1860.jpg.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 As the cotton industry continued to develop, the need for laborers increased. This demand was met with a forced migration of slaves, one of the largest in American history. In this “second middle passage,” occuring between 1790 and 1860, planters and slave traders forced over one million African Americans to travel from the Chesapeake region to the emerging Southwest. These slaves labored under grueling conditions, clearing the land for plantations and later laboring to produce cotton.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Enslaved men and women who worked on cotton plantations faced constant and often arduous labor. A bell or horn roused them at dawn. After eating breakfast, they assembled in work gangs of about twenty people. They planted in the spring, hoed weeds in the summer, and harvested in the fall. One free man of color who was captured and sold into slavery depicted a life that was frequently filled with fear. The expected day’s work during harvest was 200 pounds. Slaves walked down the long rows of cotton and plucked the ripe bolls, putting them in large sacks. Those who broke branches or stalks or who accidentally smeared their blood on the cotton were often whipped. At the end of the day, the slaves brought their cotton to the gin house in a basket. If the person did not pick enough cotton “he knows that he must suffer.” If the person picked more cotton than the quota, he or should would be expected to match that mark the next day. “So, whether he has too little or too much, his approach to the gin-house is always with fear and trembling.”

¶ 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

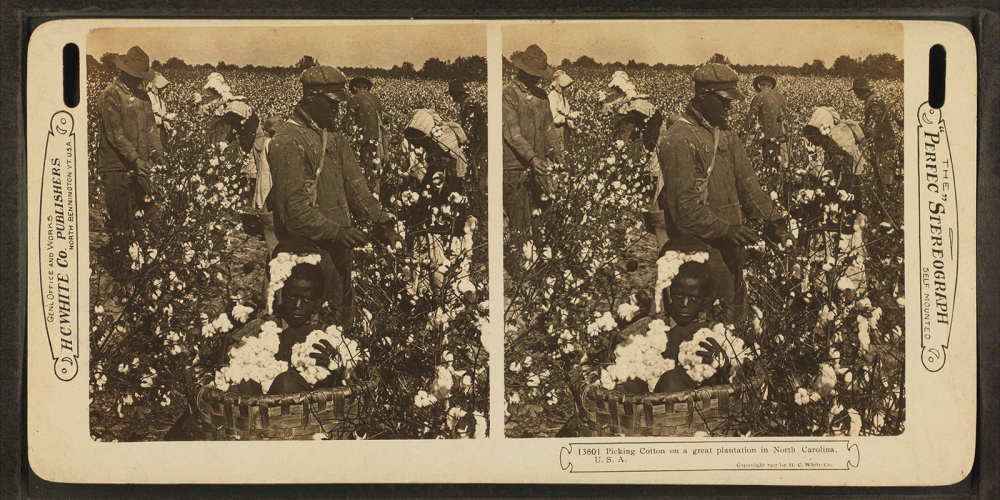

Though taken after the end of slavery, these stereographs show various stages of cotton production. The fluffy white staple fiber is first extracted from the boll (a prickly, sharp protective capsule), after which the seed is separated in the ginning and taken to a storehouse. Unknown, Picking cotton in a great plantation in North Carolina, U.S.A., c. 1865-1903. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Picking_cotton_in_a_great_plantation_in_North_Carolina,_U.S.A,_from_Robert_N._Dennis_collection_of_stereoscopic_views_2.png.

Though taken after the end of slavery, these stereographs show various stages of cotton production. The fluffy white staple fiber is first extracted from the boll (a prickly, sharp protective capsule), after which the seed is separated in the ginning and taken to a storehouse. Unknown, Picking cotton in a great plantation in North Carolina, U.S.A., c. 1865-1903. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Picking_cotton_in_a_great_plantation_in_North_Carolina,_U.S.A,_from_Robert_N._Dennis_collection_of_stereoscopic_views_2.png.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 Although many slaves perished under the regime, cotton plantations represented extraordinarily profitable enterprises. By 1860, about 70 percent of southern slaves worked on cotton plantations. The ever-escalating demand for cotton drove the price of slaves upward. In 1830, a young male field hand cost about $1,250 in New Orleans (about $30,000 in today’s dollars), but by 1860, the same slave cost an estimated $2,000 (about $42,000 today). The planters primarily responsible for this increased demand were usually self-made men who used business acumen, agricultural sense, and a bit of luck to succeed. Owning twenty or more slaves typically signified entry into the planter class, but one bad decision could force a planter to sell his or her assets, including slaves. These sales often disregarded marriages and separated children from their parents. Southern court records from across the black belt reflect the separation of slave families through public auctions.

¶ 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

![The slave markets of the South varied in size and style, but the St. Louis Exchange in New Orleans was so frequently described it became a kind of representation for all southern slave markets. Indeed, the St. Louis Hotel rotunda was cemented in the literary imagination of nineteenth-century Americans after Harriet Beecher Stowe chose it as the site for the sale of Uncle Tom in her 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. After the ruin of the St. Clare plantation, Tom and his fellow slaves were suddenly property that had to be liquidated. Brought to New Orleans to be sold to the highest bidder, Tom found himself “[b]eneath a splendid dome” where “men of all nations” scurried about. J. M. Starling (engraver), "Sale of estates, pictures and slaves in the rotunda, New Orleans,” 1842. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sale_of_Estates_Pictures_and_Slaves_in_the_Rotunda_New_Orleans.jpg.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/Sale_of_Estates_Pictures_and_Slaves_in_the_Rotunda_New_Orleans-1000x732.jpg) The slave markets of the South varied in size and style, but the St. Louis Exchange in New Orleans was so frequently described it became a kind of representation for all southern slave markets. Indeed, the St. Louis Hotel rotunda was cemented in the literary imagination of nineteenth-century Americans after Harriet Beecher Stowe chose it as the site for the sale of Uncle Tom in her 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. After the ruin of the St. Clare plantation, Tom and his fellow slaves were suddenly property that had to be liquidated. Brought to New Orleans to be sold to the highest bidder, Tom found himself “[b]eneath a splendid dome” where “men of all nations” scurried about. J. M. Starling (engraver), “Sale of estates, pictures and slaves in the rotunda, New Orleans,” 1842. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sale_of_Estates_Pictures_and_Slaves_in_the_Rotunda_New_Orleans.jpg.With the westward expansion of cotton culture in the lower South, the number of slaves required to labor on plantations in the region increased dramatically. Simultaneously, slaveholders in the upper South—which included Virginia and Maryland—were increasingly willing to supply slaves to meet the lower South’s new labor requirements as tobacco production slowed and the Nat Turner Rebellion left slaveholders fearful of large slave populations.The simplest definition for the interstate slave trade was the buying and selling of human beings. However, as the trade grew and became more sophisticated following the War of 1812, the emerging marketplace and growing infrastructure began to create a larger web of businesses. Slave markets constituted one of the key features of the trade. Cities like Washington D.C., Charleston, Richmond, and New Orleans each featured large, formal markets, although rural markets and estate and foreclosure sales also fueled the trade. Even as the traders packaged their slaves, as one historian describes, by “feeding them up, oiling their bodies, and dressing them in new clothes, they were forced to rely on the slaves to sell themselves, to act as they had been advertised to be.” In addition to procuring slaves, traders also acted as brokers and auctioneers. Slaves communicated with one another in the markets, passing information concerning upcoming sells, runaway attempts, and knowledge about different buyers.

The slave markets of the South varied in size and style, but the St. Louis Exchange in New Orleans was so frequently described it became a kind of representation for all southern slave markets. Indeed, the St. Louis Hotel rotunda was cemented in the literary imagination of nineteenth-century Americans after Harriet Beecher Stowe chose it as the site for the sale of Uncle Tom in her 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. After the ruin of the St. Clare plantation, Tom and his fellow slaves were suddenly property that had to be liquidated. Brought to New Orleans to be sold to the highest bidder, Tom found himself “[b]eneath a splendid dome” where “men of all nations” scurried about. J. M. Starling (engraver), “Sale of estates, pictures and slaves in the rotunda, New Orleans,” 1842. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sale_of_Estates_Pictures_and_Slaves_in_the_Rotunda_New_Orleans.jpg.With the westward expansion of cotton culture in the lower South, the number of slaves required to labor on plantations in the region increased dramatically. Simultaneously, slaveholders in the upper South—which included Virginia and Maryland—were increasingly willing to supply slaves to meet the lower South’s new labor requirements as tobacco production slowed and the Nat Turner Rebellion left slaveholders fearful of large slave populations.The simplest definition for the interstate slave trade was the buying and selling of human beings. However, as the trade grew and became more sophisticated following the War of 1812, the emerging marketplace and growing infrastructure began to create a larger web of businesses. Slave markets constituted one of the key features of the trade. Cities like Washington D.C., Charleston, Richmond, and New Orleans each featured large, formal markets, although rural markets and estate and foreclosure sales also fueled the trade. Even as the traders packaged their slaves, as one historian describes, by “feeding them up, oiling their bodies, and dressing them in new clothes, they were forced to rely on the slaves to sell themselves, to act as they had been advertised to be.” In addition to procuring slaves, traders also acted as brokers and auctioneers. Slaves communicated with one another in the markets, passing information concerning upcoming sells, runaway attempts, and knowledge about different buyers.

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

In southern cities like Norfolk, VA, markets sold not only vegetables, fruits, meats, and sundries, but also slaves. Enslaved men and women, like the two walking in the direct center, lived and labored next to free people, black and white. S. Weeks, “Market Square, Norfolk,” from Henry Howe’s Historical Collections of Virginia, 1845. Wikimedia.

In southern cities like Norfolk, VA, markets sold not only vegetables, fruits, meats, and sundries, but also slaves. Enslaved men and women, like the two walking in the direct center, lived and labored next to free people, black and white. S. Weeks, “Market Square, Norfolk,” from Henry Howe’s Historical Collections of Virginia, 1845. Wikimedia.

¶ 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0

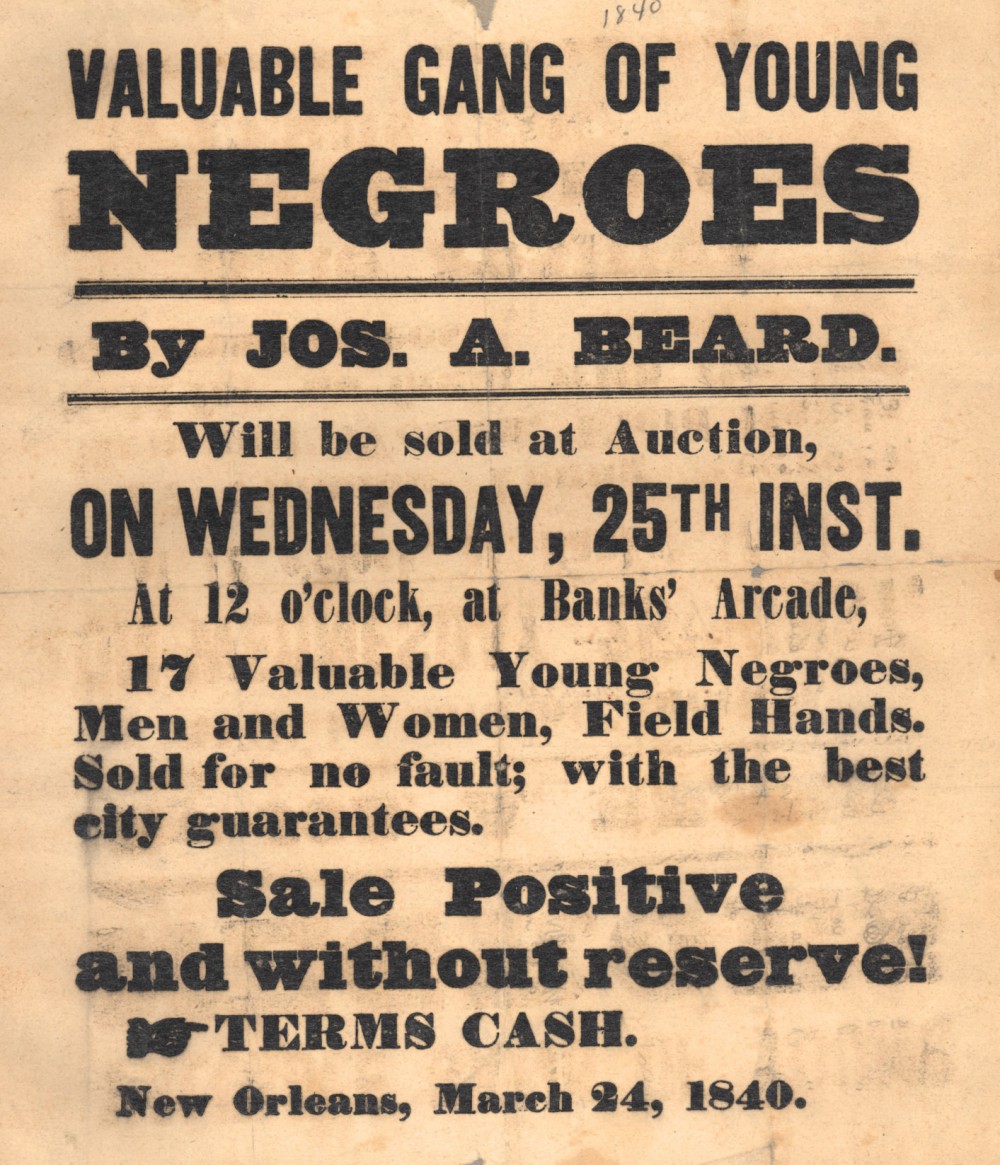

The slave trade sold bondspeople — men, women, and children — like mere pieces of property, as seen in the advertisements produced during the era. 1840 poster advertising slaves for sale in New Orleans. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ValuableGangOfYoungNegroes1840.jpeg.

The slave trade sold bondspeople — men, women, and children — like mere pieces of property, as seen in the advertisements produced during the era. 1840 poster advertising slaves for sale in New Orleans. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ValuableGangOfYoungNegroes1840.jpeg.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Abolitionists and even some southerners believed the domestic slave trade represented the most immoral qualities of the institution of slavery because it encouraged the destruction of the slave family. Itinerant, faceless slave traders represented the villains responsible for the trade and its evils, but the profitability of the trade provided a sufficient incentive for slaveholders to participate. Between 1820 and 1860, the trade facilitated $10.8 billion in annual sales. By the 1830s, pro-slavery advocates attempted to morally justify the trade by claiming that buyers protected the social order by purchasing slaves, who otherwise would not be able to take care of themselves. By the 1850s and 60s, however, southerners were plagued by numerous attacks from abolitionists and the publication of stories of slaves, like Anna in Richmond who chose to jump from the roof instead of being sold back into slavery, thus making it increasingly difficult to defend the slave trade.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Slavery in the Old South was not simply a matter of white masters and black slaves. Despite attempts by white settlers to ignore or exile indigenous peoples in the region, Native Americans remained an important component of southern society, and several Native American societies also included forms of slavery. Captivity served as a wartime tradition that facilitated trade for many southern Indians. By the antebellum period, however, members of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole) selectively blended certain aspects of Euro-American racial slavery and transitioned from slave trading to slaveholding. For example, Robert M. Jones, a Choctaw man, owned at least six plantations covering thousands of acres, 300-500 slaves, twenty-eight stores, a fleet of steamships, and elaborate mansions. Most of his wealth stemmed from both the buying and selling of black slaves and the use of their labor on his plantations.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 Forced Indian Removal in the 1830s accelerated slaveholding in Indian Nations. Choctaw Indians Mushulatubbee and Peter Pitchlynn, for instance, invested heavily in slaves immediately before removal because they knew slaves would be useful in rebuilding homes and farms in Indian Territory. These slaves made the journey on the “Trail of Tears” the same way other slaves traveled the “Second Middle Passage.” The treatment of slaves varied greatly both within and between tribes. Some slaves lived as free as their masters, but others lived and labored under the same brutal conditions found on many American plantations. Slaves belonging to the Five Tribes shared many of the cultural values of African American slaves. For instance, two Choctaw slaves named Wallace Willis and Aunt Minerva are credited with writing the famous slave songs, “Swing Lo, Sweet Chariot” and “Steal Away to Jesus.” Songs like these demonstrate the beauty and power of cultures forged in the trauma of slavery.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

III. Slave Life and Resistance

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 The concept of family played a crucial role in the daily lives of enslaved African Americans in the Old South. Family represented an institution through which slaves pieced together communities and ultimately an entire world distinct from those who exploited them. Family ties provided slaves with identities apart from their master, connections with other slaves, and ways to preserve the traditions and beliefs of their own communities. These ties also provided networks to share news, resistance tactics, and advice of all kinds.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 1 The nature and structure of the slave family changed over time. African-born slaves during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries typically engaged in unions—often polygamous—with those of the same ethnicity when possible. However, by around 1830, the growth of Christianity in slave communities increased the prevalence of nuclear families. By the start of the Civil War, approximately two-thirds of slaves were members of nuclear households, each household averaging six persons. The remaining third of slaves resided with only one or neither biological parent.

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 Many slave marriages endured for many years, although the threat of sale always loomed. The increased interstate slave trade after the turn of the nineteenth century accounted for the dissolution of hundreds of thousands of slave families. In the decades before the Civil War, between one-fifth and one-third of all slave marriages were broken up via sale or forced migration. Slaveholders also disrupted slave families for a variety of other reasons, selling slaves they considered disobedient, mutinous, unproductive, unhealthy, or even infertile. Law and custom that defined slaves as property enabled slaveholders to bequeath their slaves to heirs, present them as gifts, or offer them to settle debts.

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 Planters justified their position of power using the logic of paternalism. Paternalism implied that masters would serve as “fathers” or “mothers” who would care for their slaves as they would children. This ideology created a way for some slaves to manipulate masters into giving them better treatment, but paternalism always replicated an inequality in power relations and undercut the autonomy of slave families. In a society that so often venerated the authority of men over wives and children, slavery imposed a very different set of expectations on slave men and women.

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 Though most enslaved women performed field labor similar to their male counterparts, the experience of slavery affected men and women in different ways. Enslaved women were particularly vulnerable to sexual violence. Harriet Jacobs, an enslaved woman from North Carolina, chronicled her master’s attempts to sexually abuse her in her narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Jacobs suggested that her successful attempts to resist sexual assault and her determination to love whom she pleased was “something akin to freedom.” Jacobs’ ability to choose her own lover and spouse was unfortunately not possible for many enslaved women. Rape of slave women was common and could even be used by white men to terrorize both enslaved men and women. Women constantly faced the threat of sexual violence, and multiple accounts exist of men forced to watch as masters raped their wives or children. An absence of laws addressing the rape of slaves allowed for the constant barrage of sexual assault. One enslaved woman from Missouri, Celia, murdered her master after he raped her repeatedly for five years. The rape was overlooked in the courtroom, and Celia was hanged for the murder.

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 White women and enslaved women were both subject to the authority of white men, yet this did not mean that white women were particularly sympathetic to slaves. White women frequently inflicted physical violence upon their slaves, particularly women, who often worked in close proximity to the household. This type of abuse constituted another way of asserting power within the household. Harriet Jacobs noted that once news of her master’s intentions to sexually exploit her became clear, her mistress became increasingly distrustful of Jacobs, and Jacobs feared for her life.

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 Slaves could and did resist those who sought to exploit them, both through minor acts of everyday resistance and through organized rebellions. On the morning of August 22, 1831 in Southampton County, Virginia, Nat Turner and six collaborators attempted to free the region’s enslaved population. Turner initiated the violence by killing his master with an axe blow to the head. By the end of the day, Turner and his band, which had grown to over fifty men, killed fifty-seven white men, women, and children on eleven farms. By the next day, the local militia and white residents had captured or killed all of the participants except Turner, who hid for a number of weeks in nearby woods before being captured and executed.

¶ 32

Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0

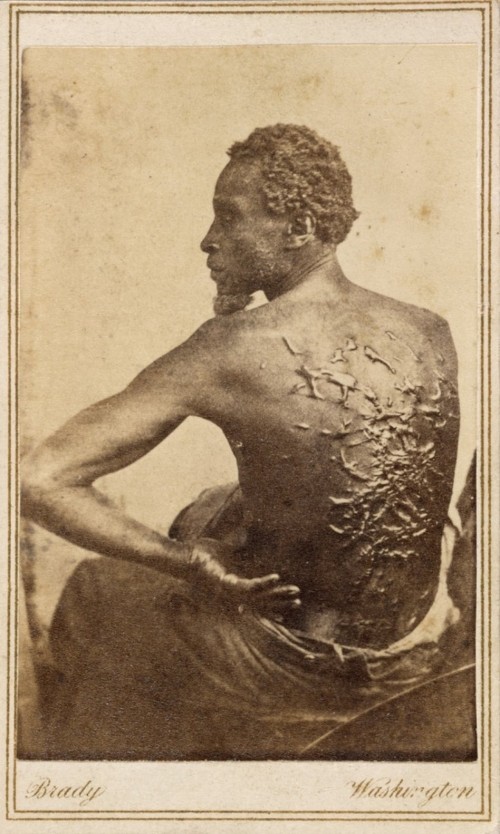

Gordon, pictured here, endured terrible brutality from his master before escaping to Union Army lines in 1863. He would become a soldier and help fight to end the violent system that produced the horrendous scars on his back. Matthew Brady, Gordon, 1863. Wikimedia.

Gordon, pictured here, endured terrible brutality from his master before escaping to Union Army lines in 1863. He would become a soldier and help fight to end the violent system that produced the horrendous scars on his back. Matthew Brady, Gordon, 1863. Wikimedia.

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 Turner’s rebellion revived white anxieties about a massive slave uprising, fearing the United States would fall to the same fate as Haiti some years earlier. In response to the rebellion, white Virginians cracked down on the state’s African American population. Hundreds of enslaved and free blacks were arrested, deported, or executed, regardless of their involvement in the uprising. Virginia’s legislature passed new restrictions on the free black population—particularly on their interstate mobility—believing that they could be a negative influence on what they believed was an otherwise contented slave population.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 Many whites denied that enslaved people would rebel simply against the inhumanity of slavery itself, instead blaming growing abolitionist sentiment in the North for the uprising. William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper The Liberator was first published in Boston the year Turner and his men took up arms, and David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World had recently appeared in the hands of black Virginians as well. As in other rare instances of insurrections, whites in Virginia placed the blame for the uprising on outsiders—particularly abolitionists and free blacks—and strengthened their defense of slavery.

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 Nine years before Turner’s rebellion, fears of widespread slave insurrection shook the South Carolina Lowcountry. According to white authorities, a free black Charleston man by the name of Denmark Vesey had organized enslaved and free black inhabitants with the purpose of staging a bloody revolt. Days before the revolt was to take place, fearful slaves revealed the plot to white authorities, leading to swift retribution. Vesey and some thirty-five other blacks were tried and hanged, and others were sold into slavery in the West Indies. The planned revolt inflamed the racial anxieties of whites in Charleston and throughout the South Carolina Lowcountry. In response to the conspiracy, the legislature passed new laws restricting manumission and the mobility of free blacks and created a new guard to protect Charleston against future insurrections.

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0 In recent years, some historians have begun to doubt the commonly accepted Vesey story. Historian Michael P. Johnson in particular has questioned whether a conspiracy existed at all, suggesting it may have been a fabrication of white authorities for their use as a political issue. Most historians continue to believe Vesey was involved in some kind of insurrection plot in the summer of 1822, but the scope and scale of the rebellion remains under debate. Like other southern slave insurrections both real and imagined, the prospect of black-on-white violence stoked the racial fears of many white southerners.

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0

IV. Migration and Geographies

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 Urban growth remained tempered in the American South throughout the colonial period, but several key cities did emerge in correlation with the expansion of staple, or cash crop, agriculture. Towns provided central points for new capital investment and places where the English government could exert its control. The early establishment of towns remained tied to the needs of growing plantation economies. Towns were predominantly located along rivers or seaports.

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Tobacco production in the Chesapeake region failed to justify urban sites to facilitate export in the seventeenth century, The development of the wheat trade, however, required centralized marketing and storage, which eventually resulted in the development of Baltimore, Richmond, and Fredericksburg. During the colonial period, Charleston also emerged as an important trade capital as thousands of slaves demanded by the growing plantation economy of the lower South entered the port and a variety of goods required by the planters of the West Indies were sent southward. However, urban growth accelerated greatly with the rise in rice cultivation, which required similar marketing, processing, and storage as wheat. By 1775, Charleston represented the largest city in the South and the fourth largest city in British North America, behind Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. In addition to their key role in trade, the older seaport cities of the South like Charleston and Savannah played an important roles as points of escape for wealthier members of the planter class. During the hotter months, cities posed a welcome sanctuary from the ravages of common diseases, including yellow fever and malaria, but during the winter and early spring, a different sort of “season,” emerged; the city became the cornerstone of social and intellectual life in the South as a variety of balls and events annually entertained city residents.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 New Orleans rose to prominence as the cotton trade developed, surpassing Charleston by 1830 to become the definitive urban capital of the South. The Crescent City became home to the nation’s largest slave market and exported more cotton than any other American port, which for several decades before the Civil War allowed it to rival New York for the most important export port in the United States. By 1860, New Orleans was the sixth largest city in the country and boasted a population of 169,000 souls, while Charleston claimed a population one quarter of that size, placing it outside of the twenty largest cities. Eventually, Mobile, Memphis, and smaller towns like Natchez would also dot the cotton belt, fueling the plantation economy through the trade of slaves, manufactured goods, and cotton.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 Southern cities differed from northern cities in several important ways. A significant number of slaves could be found in every southern city. By 1860, slaves comprised more than 20 percent of the urban population of the South’s major cities, and in certain cities, the proportion could be much higher. When Fredrika Bremer visited Charleston in 1850, she could clearly see that blacks outnumbered the city’s white inhabitants: “Negroes swarm the streets. Two-thirds of the people one sees in town are negroes.” Free African Americans also gravitated towards cities in great numbers because they were afforded greater economic opportunities and ultimately were able to develop their own rich, independent religious communities and social organizations. Free people of color in New Orleans—or gens du couleur as they were called in French—accumulated significant property and wealth, and benefited from associations with whites fostered by the French and Spanish influences unique to Louisiana.

¶ 42

Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0

Free people of color were present throughout the American South, particularly in urban areas like Charleston and New Orleans. Some were relatively well off, like this femme de couleur libre who posed with her mixed-race child in front of her New Orleans home, maintaining a middling position between free whites and unfree blacks. Free woman of color with quadroon daughter; late 18th century collage painting, New Orleans. Wikimedia

Free people of color were present throughout the American South, particularly in urban areas like Charleston and New Orleans. Some were relatively well off, like this femme de couleur libre who posed with her mixed-race child in front of her New Orleans home, maintaining a middling position between free whites and unfree blacks. Free woman of color with quadroon daughter; late 18th century collage painting, New Orleans. Wikimedia

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 Enslaved and free African Americans performed a myriad of skilled and unskilled jobs vital to the economy of the city. Women served primarily as domestics, and men worked in a variety of trades relating to local and export commerce, construction, and industry. Day laborers transported goods to ships for export, whereas a variety of slave mechanics or artisans constructed ships or buildings as carpenters, or worked as wheelwrights, cabinetmakers, or in a variety of other fields. The great demand for short-term labor in cities gave rise to the practice of slave hiring. Masters would arrange either for their slaves to work for an employer, creating a contract for predetermined wages that would typically last between one month and one year, or would allow the slave to find employment with the understanding that he or she would pay a pre-arranged sum on a weekly or monthly basis for the privilege of “hiring out.” In some cities, like Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans, city governments required these slaves who were hired out by the day to wear badges and regulated the wages they would be compensated for specific jobs.

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 During the nineteenth century, urban growth accelerated in the South, although most cities retained a lighter population density than their northern counterparts primarily due to the continued preeminence of the rural economy. Although most Southern cities resisted the forces of industrialization during the antebellum period, in a handful of cities—including Richmond, Baltimore, New Orleans, and Mobile—small-scale industry did dominate the economy. Industries in these cities that centered on shipbuilding and the manufacturing of iron, chemicals, textiles, and other goods employed whites as well as free and enslaved blacks. The growth of these urban industries also further diversified the population of Southern cities as they attracted significant populations of British, Irish and German immigrants who otherwise settled outside of the South.

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 As far back as the Colonial period, Irish immigrants had found the South to be a hospitable place of settlement. In 1765, Ulster-born immigrant and Native American trader John Rea wrote home to Belfast, in the hopes of recruiting Irish settlers to populate his new Queensborough township in Georgia. He promised immigrants 100 acres of land per family, domestic animals and farming supplies. Above all, he guaranteed that their lives the South would be better than in Europe. Rea boasted to his Belfast readers, “I keep as plentiful a table as most gentlemen in Ireland, with good punch, wine, and beer.”

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 The social and cultural lives of Irish men and women varied based on the region in North America in which they settled. Many migrants moved to and lived in northern cities, particularly after the famines of the 1840s, but the American South also attracted sizable populations of Irish settlers starting in the colonial period. Indentured servants signed contracts for seven years’ labor as payment for travel costs, and often served as initial laborers on cotton plantations prior to the height of the slave trade.. Irish traders, like George Galphin, exchanged goods and created families with regional Native Americans well into the 1700s. Immigrants became planters, slaveholders, merchants and businessmen in bustling southern seaports like Charleston, New Orleans and Savannah.

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 Early settlers came from all regions in Ireland, and they represented both Catholic and Protestant denominations. Some large communities, like the Scots Irish, settled in family groups in the western Carolinas, Kentucky and Tennessee before 1800. Many migrated as entrepreneurs, and they often socialized with their non-Irish neighbors professionally and personally.

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 The ready availability of slaves in the South presented immigrants with strong labor competition. In the decades after the 1845 Potato Famine in particular, those seeking opportunities in the United States were poor Irish migrants—especially Catholics—who sought skilled and unskilled employment that placed them in direct competition with slaves. As a result, fewer immigrants moved to the South. By 1860, in fact, only 11 percent (or 200,000 persons) of the 1.6 million Irish persons living in the United States resided in the southern states.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 A majority of these immigrants settled in regional urban centers, like Charleston, Mobile, Natchez, New Orleans and Savannah. There, they made a major impact on developing infrastructure, especially by laboring on canals and railroads meant to improve trade efficiency. This work was unpleasant and arduous, and the fact that southerners used Irish settlers for dangerous labor they would not even have slaves do earned them nicknames like “black” and “smoked.” New immigrants were aware that such work fostered an association with slaves, and many tried to distinguish themselves publically from African-Americans. Consequently, Irishmen and women often supported the racial distinctions undergirding slave society in the Old South, even as men like Daniel O’Connell linked support for abolitionism to Irish nationalism during the 1830s. Later Irish settlers in the Old South later became more socially and culturally “Irish” than their southern predecessors as they settled increasingly in ethnocentric neighborhoods and churches.

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 Caribbean influences joined with European traditions in crafting the unique culture of the Old South. This connection is particularly clear in the development of southern food. For instance, New Orleans’ Creole cuisine, was heavily influenced by Caribbean, West African, European, and American Indian culinary traditions. New Orleans and colonial Haiti, in particular, had an intimately connected history. Following the Haitian Revolution, an estimated 10,000 free and enslaved Haitians came to New Orleans, nearly doubling city’s population. The strong cultural continuities between the two cultures reinforced the preexisting creolized cultures of Louisiana that arose from French and Spanish influences.

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 The South drew fewer immigrants than did the North, but antebellum southern culture nonetheless reflected the diverse people who came to understand the region as their home.

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 Just as new southerners were arriving, others were leaving. Escaped slaves sought refuge in the northern states, and then later in Canada, while other African Americans looked across the ocean for a place to start a new life. The South was intimately connected to the wider world through migrations, both free and forced, as well as economic relationships, and cultural ties.

¶ 53

Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0

Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty–The Fugitive Slaves, 1862. Wikimedia.

Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty–The Fugitive Slaves, 1862. Wikimedia.

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 The American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded in 1816 with the purpose of raising money to send manumitted slaves to West Africa. The idea of sending African Americans to Africa had been pioneered decades earlier by the British who established a colony in Sierra Leone. Some members of the ACS, like the Reverend Robert Finely, opposed slavery for religious reasons and also believed that Liberia could serve as an outpost for spreading Christianity to indigenous peoples. The ACS also received support from white politicians, like Senator Henry Clay, who believed that colonization could atone for the evils of slavery. Many slaveholders believed that freed slaves endangered the institution of slavery, and therefore removing former slaves from the states, allowed slaveholders to manumit their slaves without such danger.

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 In 1819, the small island called “Providence Island” was purchased for the use of the African American colonists. The settlement was later named “Monrovia” in honor of American president and ACS supporter James Monroe (1817-1825). The first colonists arrived one year later, and over the course of the nineteenth century, more than 19,000 African Americans settled in Liberia. Many colonists died from disease—particularly malaria—and famine. Indigenous Africans, including Dey and Grebo peoples, viewed colonists as intruders and occupiers. Wars between the colonists and native peoples continued throughout the nineteenth century. Many African Americans were suspicious of the ACS’ intentions in sending them to a far-off land, and reports of the colony’s troubles increased that doubt. David Walker’s echoed the sentiments of many other free African Americans in his famous Appeal when he asked, “[w]hy should they send us into a far country to die?”

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 Liberia did offer formerly enslaved African Americans opportunities for success. Lott Cary, who was born a slave in Virginia, eventually purchased his freedom and migrated to Liberia as one of the first American missionaries to be sent abroad. He established the colony’s first church, Providence Baptist. African American newspaperman, John Brown Russwurm, operated the colony’s first printing press, publishing the monthly Liberia Herald. Other colonists, like Matilda Lomax, used freedom to educate their children, something they would not have been legally allowed to do in the South.

¶ 57

Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0

The issue of emigration elicited disparate reactions from African Americans. Tens of thousands left the United States for Liberia, a map of which is shown here, to pursue greater freedoms and prosperity. Most emigrants did not experience such success, but Liberia continued to attract black settlers for decades. J. Ashmun, Map of the West Coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Cape Palmas, including the colony of Liberia…, 1830. Library of Congress.

The issue of emigration elicited disparate reactions from African Americans. Tens of thousands left the United States for Liberia, a map of which is shown here, to pursue greater freedoms and prosperity. Most emigrants did not experience such success, but Liberia continued to attract black settlers for decades. J. Ashmun, Map of the West Coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Cape Palmas, including the colony of Liberia…, 1830. Library of Congress.

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 The ACS maintained control of Liberia and appointed the colony’s political officials until 1847. White supporters of the ACS and other societies continued to provide the money and goods necessary for the passage to Liberia. White men and women aided with establishing schools, missionary outposts, and trading entrepôts in Liberia.

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0 Freed African Americans exhibited mixed feelings concerning emigration. In 1787, Prince Hall petitioned the Massachusetts General Court to provide support for the repatriation of African Americans to Africa but was ultimately rebuffed. Hall later worked to organize emigration to Haiti. Paul Cuffee, a black sailor and successful merchant organized the earliest successful effort to resettle in Africa. In 1815 he brought thirty-four settlers to Sierra Leone on one of his own ships. Although Cuffe understood emigration as a way to leave behind American racism, his significant personal and financial investment in emigration was rooted in his desire to establish a global trade route.

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0 Most African Americans opposed colonization, preferring to remain in the United States, in part because emigration would mean abandoning enslaved family members. Opposition to the ACS among African Americans became more pronounced in the 1830s, guided by fears that the ACS would eventually support forced colonization. But emigration was still an attractive option for many, so several thousand African Americans organized alternate missions and settled in Haiti and Canada. Those projects stalled by the end of the 1830s, but during the 1820s, 1830s and 1850s, the Haitian government actively recruited African Americans, offering plots of land and funds for resettlement.

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 The passage of the Fugitive Slave Law (1850) and the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision (1857) revived interest in emigration and colonization. In 1858, the Philadelphia minister Henry Highland Garnet formed the African Civilization Society, which emphasized black self-determination and the conversion of Africans to Christianity while repudiating American racism. Martin Delany later joined forces with Garnet, although both men had vigorously opposed colonization only a few years earlier. Hostility towards colonization remained strong in the African American community until the end of slavery. At its heart, the debate over emigration raised questions about whether Africa ought to be lauded as the homeland of blacks in the United States or whether claims to freedom and equality in the United States that remained unmet were enough to claim an American identity.

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0

V. Culture in the Old South

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 Southern culture was strongly shaped by religion. Before the American Revolution, the Anglican Church served as the established church throughout the southern colonies. The rise of Protestant evangelicalism in the 1740s posited a fledgling alternative to the Anglican establishment. For evangelicals, the conversion experience was upheld as a universally attainable route to spiritual salvation. It employed highly emotional sermons and liturgies—many of them at large, interdenominational, outdoor camp meetings—to facilitate this conversion experience among believers.

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0 British defeat in the American Revolution further transformed religion in the South as many rejected the Anglican Church as an institution of the British Crown. When the United States of America rejected any religious establishment, the Anglican Church, now renamed the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States, suffered. Many former Anglicans became Episcopalians, but others drifted off to other denominations, including the Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians.

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0 Influential Jewish and Catholic minorities also emerged in some of the South’s urban areas, notably New Orleans, Savannah, and Charleston. By 1800, Charleston had the largest Jewish population in the United States, a distinction it retained until around 1830 when it was surpassed by New York City. Jewish settlers began arriving in South Carolina as early as the late seventeeth century as they fled from persecution under the Spanish Inquisition. Reform Judaism had its roots is in the antebellum South as the members of Congregation Beth Elohim in Charleston began to modernize the faith. From these roots in Charleston, Reform Judaism took its formal shape in Ohio under the leadership of Isaac Mayer Wise and blossomed into the largest Jewish denomination in the United States.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0 Catholics had established permanent settlements in Spanish Florida prior to the creation of Jamestown. Rivalries between Catholic Spain and later Catholic France inhibited the growth of Catholicism in British North America. Catholicism became the largest denomination in the United States by 1850, but most of this growth owed to immigrants in the northern states. Southern Catholicism nonetheless represented an important minority in the South, and in some cities, particularly New Orleans, Catholicism dominated the social life of many southerners.

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0 While the South contained important pockets of religious diversity, the evangelicalism of the Second Great Awakening established the region’s prevailing religious culture. Led by Methodists, Baptists, and to a lesser degree, Presbyterians, this intense period of religious revivals swept the along southern backcountry. By the outbreak of the Civil War, the vast majority of southerners who affiliated with a religious denomination belonged to either the Baptist or Methodist faith. Both churches in the South eventually became some of the most vocal defenders of slavery.

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0 Southern ministers contended that God himself had selected Africans for bondage but also considered the evangelization of slaves to be one of their greatest callings. Missionary efforts among southern slaves increased Protestantism among African Americans, leading to a proliferation of biracial congregations and prominent independent black churches. Some black and white southerners forged positive and rewarding biracial connections; however, more often black and white southerners described strained or superficial religious relationships.

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 1 As the institution of slavery hardened racism in the South, relationships between missionaries and Native Americans transformed as well. Missionaries of all denominations were among the first to represent themselves as “pillars of white authority.” After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, plantation culture expanded into the Deep South, and mission work became a crucial element of Christian expansion. Frontier mission schools carried a continual flow of Christian influence into indigenous communities. Some missionaries learned indigenous languages, but many more worked to prevent indigenous children from speaking their native tongues, insisting upon English for Christian understanding. By the Indian removals of 1835 and the Trail of Tears in 1838, missionaries in the South preached a pro-slavery theology that emphasized obedience to masters, the biblical basis of racial slavery via the curse of Ham, and the “civilizing” paternalism of slave-owners.

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0 Slaves most commonly received Christian instruction from white preachers or masters, whose religious message typically stressed slave subservience. Anti-literacy laws ensured that most slaves would be unable to read the Bible in its entirety and thus could not acquaint themselves with such inspirational stories as Moses delivering the Israelites out of slavery. Contradictions between God’s Word and master and mistress cruelty and inhumanity did not pass unnoticed by many enslaved African Americans. As former slave William Wells Brown declared, “slaveholders hide themselves behind the Church,” adding that “a more praying, preaching, psalm-singing people cannot be found than the slaveholders of the South.”

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0 Many slaves chose to create and practice their own versions of Christianity, one that typically incorporated aspects of traditional African religions with limited input from the white community. Nat Turner, for example, found inspiration from religion early in life. Adopting an austere Christian lifestyle during his adolescence, Turner claimed to have been visited by “spirits” during his twenties, and considered himself something of a prophet. He claimed to have had visions, in which he was called upon to do the work of God, leading some contemporaries (as well as historians) to question his sanity. Coupled with the “Baptist War” in Jamaica later that year—in which Baptist missionaries were alleged to have encouraged enslaved people to revolt—Nat Turner’s rebellion caused some whites to limit independent black churches. These independent religious communities served as one of the key sources of slave resistance. But despite the importance of independent black churches, the story of religion in the South is ultimately a story of biracial congregations.

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0 When antislavery and abolitionist critiques began to usher forth from northern pulpits in the 1820s and1830s, socially prominent Protestant Evangelicals developed staunch proslavery positions, using religious faith to justify slavery. Debates over slavery led to a split between northern and southern congregations, beginning with the Presbyterian schism of 1837, followed by the Methodists in 1844 and the Baptists in 1845

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 Evangelical religion reinforced other elements of southern culture, including an obsession with masculine honor. Honor prioritized the public recognition of white masculine claims to reputation and authority. It also encouraged men to privately reflect on their behavior and reputation.

¶ 74 Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0 Southern men developed a code to ritualize their interactions with each other and to perform their expectations of honor. This code structured language and behavior and was designed to minimize conflict. But when conflict did arise, the code also provided rituals that would reduce the resulting violence.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0 The formal duel exemplified the code in action. If two men could not settle a dispute through the arbitration of their friends, they would exchange pistol shots to prove their equal honor status. Duelists arranged a secluded meeting, chose from a set of deadly weapons and risked their lives as they clashed with swords or fired pistols at one another. Some of the most illustrious men in American history participated in a duel at some point during their lives, including President Andrew Jackson, Vice-President Aaron Burr, United States Senators Henry Clay, and Thomas Hart Benton. In all but Burr’s case, dueling assisted in elevating these men to prominence. For Burr, however, killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel, a much beloved Founding Father, began the downward spiral of his political career.

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 During the 1830s, religious piety became integrated into the honor creed, creating an ethic of “righteous honor.” It emphasized restraint as the surest path to moral righteousness, but allowed for the justification of violence when threatened with moral corruption. Righteous honor governed male interactions and extended by proxy over their households and dependents—male and female, white and black—over whom they exercised authority. Domestic disorder threatened personal honor, which threatened public disgrace.

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 0 Dueling contrasted deeply with other forms of violence more common among those in lower social positions. Canings, whippings, and clubbings were also used to preserve ones reputation, but such acts were typically applied to men deemed socially unequal and, unlike dueling, the violent act intended to demonstrate that the man assaulted was no better than a slave. The most prevalent form of violence in the South was directed at those men and women in bondage. Violence manifested itself in the form of whippings, beatings, and even sexual assaults, including rape.

¶ 78 Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0 Violence amongst the lower classes, especially those in the backcountry, involved fistfights and shootouts. Tactics included the sharpening of fingernails and filing of teeth into razor sharp points, which would be used to gouge eyes and bite off ears and noses. In a duel, a gentleman achieved recognition by risking his life rather than killing his opponent, whereas those involved in rough-and-tumble fighting achieved victory through maiming their opponent.

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0 The legal system was partially to blame for the prevalence of violence in the Old South. Although states and territories had laws against murder, rape, and various other forms of violence, including specific laws against dueling, upper-class southerners were rarely prosecuted and juries often acquitted the accused. Despite the fact that hundreds of duelists fought and killed one another, there is little evidence that many duelists faced prosecution, and only one, Timothy Bennett (Belleville, Illinois), was ever executed. By contrast, prosecutors routinely sought cases against lower-class southerners, who were found guilty in greater numbers than their wealthier counterparts.

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0 The southern emphasis on honor affected women as well. While southern men worked to maintain their sense of masculinity, so too southern women cultivated a sense of femininity. Femininity in the South was intimately tied to the domestic sphere, even more so than for women in the North. The cult of domesticity strictly limited the ability of wealthy southern women to engage in public life. While northern women began to organize reform societies, southern women remained bound to the home where they were instructed to cultivate their families’ religious sensibility and manage their household. Managing the household was not easy work, however. For women on large plantations, managing the household would include directing a large bureaucracy of potentially rebellious slaves. For the vast majority of southern women who did not live on plantations, managing the household would include nearly constant work in keeping families clean, fed, and well-behaved. On top of these duties, many southern women would be required to assist with agricultural tasks.

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0 Scarlett O’Hara’s fictional life was filled with leisure. The reality for southern women was far less glamorous. Maintaining order in a society rooted in slavery required a constant presence of violence, and this violence hung over the Old South, haunting men and women; white, black, and Native American. Despite the brutality of slavery and the dominance of cotton, the Old South was a place of diversity and cultural innovation. So much of what would later become mainstream American culture had its origins in the Old South.

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0

VI. Conclusion

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0 Despite all of its misconceptions of the Old South, Gone With the Wind nevertheless hinted at the great transformations brought by the Civil War. White southerners would work to preserve the status quo after emancipation, but the Old South disappeared with the defeat of the Confederacy.

Remind readers that slavery was not confined to the South