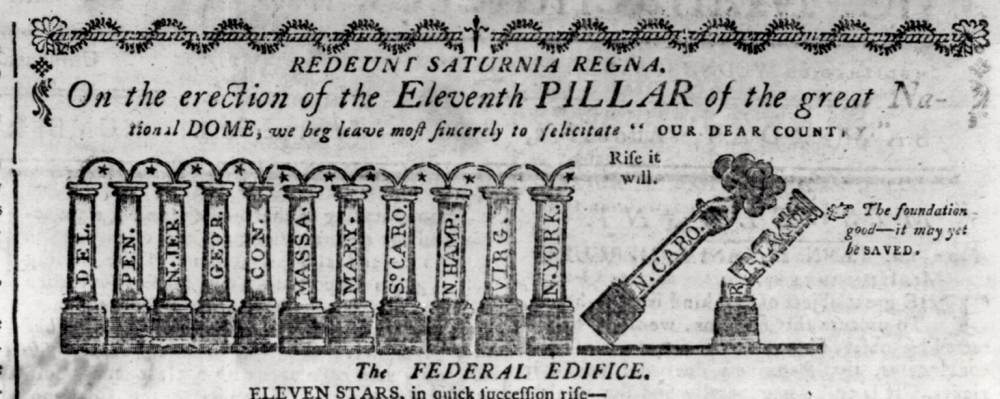

“The Federal Pillars,” from The Massachusetts Centinel, August 2, 1789, via Library of Congress.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

On July 4, 1788, Philadelphians turned out for a “grand federal procession” in honor of the new national constitution. Workers in various trades and professions demonstrated. Blacksmiths carted around a working forge, on which they symbolically beat swords into farm tools. Potters proudly carried a sign paraphrasing from the Bible, “The potter hath power over his clay,” linking God’s power with an artisan’s work and a citizen’s control over the country. Christian clergymen meanwhile marched arm-in-arm with Jewish rabbis. The grand procession represented what many Americans hoped the United States would become: a diverse but cohesive, prosperous nation.1

Over the next few years, Americans would celebrate more of these patriotic holidays. In April 1789, for example, thousands gathered in New York to see George Washington take the presidential oath of office. That November, Washington called his fellow citizens to celebrate with a day of thanksgiving, particularly for “the peaceable and rational manner” in which the government had been established.2

But the new nation was never as cohesive as its champions had hoped. Although the officials of the new federal government—and the people who supported it—placed great emphasis on unity and cooperation, the country was often anything but unified. The Constitution itself had been a controversial document adopted to strengthen the government so that it could withstand internal conflicts. Whatever the later celebrations, the new nation had looked to the future with uncertainty. Less than two years before the national celebrations of 1788 and 1789, the United States had faced the threat of collapse.

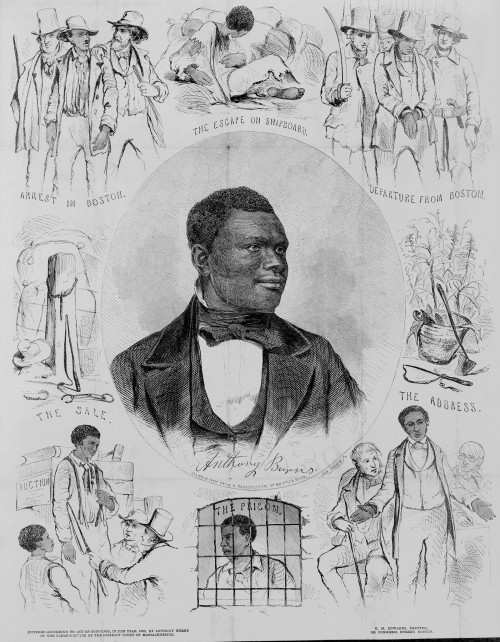

II. Shays’ Rebellion

Daniel Shays became a divisive figure, to some a violent rebel seeking to upend the new American government, to others an upholder of the true revolutionary virtues Shays and others fought for. This contemporary depiction of Shays and his accomplice Job Shattuck portrays them in the latter light as rising “illustrious from the Jail.” Unidentified Artist, Daniel Shays and Job Shattuck, 1787. Wikimedia.

In 1786 and 1787, a few years after the Revolution ended, thousands of farmers in western Massachusetts were struggling under a heavy burden of debt. Their problems were made worse by weak local and national economies. Many political leaders saw both the debt and the struggling economy as a consequence of the Articles of Confederation which provided the federal government with no way to raise revenue and did little to create a cohesive nation out of the various states. The farmers wanted the Massachusetts government to protect them from their creditors, but the state supported the lenders instead. As creditors threatened to foreclose on their property, many of these farmers, including Revolutionary War veterans, took up arms.

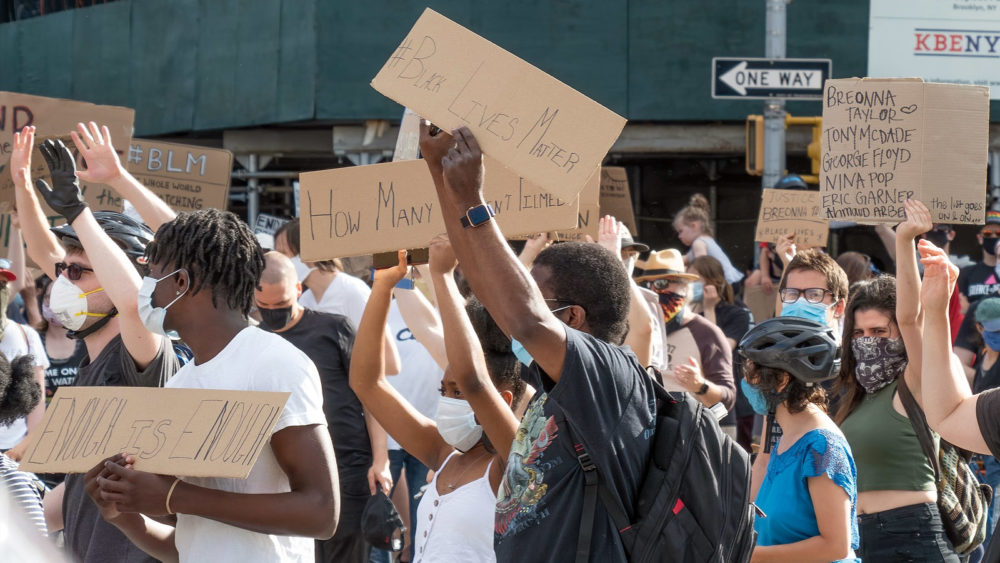

Led by a fellow veteran named Daniel Shays, these armed men, the “Shaysites,” resorted to tactics like the patriots had used before the Revolution, forming blockades around courthouses to keep judges from issuing foreclosure orders. These protestors saw their cause and their methods as an extension of the “Spirit of 1776”; they were protecting their rights and demanding redress for the people’s grievances.

Governor James Bowdoin, however, saw the Shaysites as rebels who wanted to rule the government through mob violence. He called up thousands of militiamen to disperse them. A former Revolutionary general, Benjamin Lincoln, led the state force, insisting that Massachusetts must prevent “a state of anarchy, confusion and slavery.”3 In January 1787, Lincoln’s militia arrested more than one thousand Shaysites and reopened the courts.

Daniel Shays and other leaders were indicted for treason, and several were sentenced to death, but eventually Shays and most of his followers received pardons. Their protest, which became known as Shays’ Rebellion, generated intense national debate. While some Americans, like Thomas Jefferson, thought “a little rebellion now and then” helped keep the country free, others feared the nation was sliding toward anarchy and complained that the states could not maintain control. For nationalists like James Madison of Virginia, Shays’ Rebellion was a prime example of why the country needed a strong central government. “Liberty,” Madison warned, “may be endangered by the abuses of liberty as well as the abuses of power.”4

III. The Constitutional Convention

The uprising in Massachusetts convinced leaders around the country to act. After years of goading by James Madison and other nationalists, delegates from twelve of the thirteen states met at the Pennsylvania state house in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. Only Rhode Island declined to send a representative. The delegates arrived at the convention with instructions to revise the Articles of Confederation.

The biggest problem the convention needed to solve was the federal government’s inability to levy taxes. That weakness meant that the burden of paying back debt from the Revolutionary War fell on the states. The states, in turn, found themselves beholden to the lenders who had bought up their war bonds. That was part of why Massachusetts had chosen to side with its wealthy bondholders over poor western farmers.5

James Madison, however, had no intention of simply revising the Articles of Confederation. He intended to produce a completely new national constitution. In the preceding year, he had completed two extensive research projects—one on the history of government in the United States, the other on the history of republics around the world. He used this research as the basis for a proposal he brought with him to Philadelphia. It came to be called the Virginia Plan, named after Madison’s home state.

James Madison was a central figure in the reconfiguration of the national government. Madison’s Virginia Plan was a guiding document in the formation of a new government under the Constitution. John Vanderlyn, Portrait of James Madison, 1816. Wikimedia.

The Virginia Plan was daring. Classical learning said that a republican form of government required a small and homogenous state; the Roman republic, or a small country like Denmark, for example. Citizens who were too far apart or too different could not govern themselves successfully. Conventional wisdom said the United States needed to have a very weak central government, which should simply represent the states on certain matters they had in common. Otherwise, power should stay at the state or local level. But Madison’s research had led him in a different direction. He believed it was possible to create “an extended republic” encompassing a diversity of people, climates, and customs.

The Virginia Plan, therefore, proposed that the United States should have a strong federal government. It was to have three branches—legislative, executive, and judicial—with power to act on any issues of national concern. The legislature, or Congress, would have two houses, in which every state would be represented according to its population size or tax base. The national legislature would have veto power over state laws.6

Other delegates to the convention generally agreed with Madison that the Articles of Confederation had failed. But they did not agree on what kind of government should replace them. In particular, they disagreed about the best method of representation in the new Congress. Representation was an important issue that influenced a host of other decisions, including deciding how the national executive branch should work, what specific powers the federal government should have, and even what to do about the divisive issue of slavery.

For more than a decade, each state had enjoyed a single vote in the Continental Congress. Small states like New Jersey and Delaware wanted to keep things that way. The Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman, furthermore, argued that members of Congress should be appointed by the state legislatures. Ordinary voters, Sherman said, lacked information, were “constantly liable to be misled,” and “should have as little to do as may be” about most national decisions.7 Large states, however, preferred the Virginia Plan, which would give their citizens far more power over the legislative branch. James Wilson of Pennsylvania argued that since the Virginia Plan would vastly increase the powers of the national government, representation should be drawn as directly as possible from the public. No government, he warned, “could long subsist without the confidence of the people.”8)

Ultimately, Roger Sherman suggested a compromise. Congress would have a lower house, the House of Representatives, in which members were assigned according to each state’s population, and an upper house, which became the Senate, in which each state would have one vote. This proposal, after months of debate, was adopted in a slightly altered form as the “Great Compromise”: each state would have two senators, who could vote independently. In addition to establishing both types of representation, this compromise also counted a slave as three-fifths of a person for representation and tax purposes.

The delegates took even longer to decide on the form of the national executive branch. Should executive power be in the hands of a committee or a single person? How should its officeholders be chosen? On June 1, James Wilson moved that the national executive power reside in a single person. Coming only four years after the American Revolution, that proposal was extremely contentious; it conjured up images of an elected monarchy.9 The delegates also worried about how to protect the executive branch from corruption or undue control. They endlessly debated these questions, and not until early September did they decide the president would be elected by a special “electoral college.”

In the end, the Constitutional Convention proposed a government unlike any other, combining elements copied from ancient republics and English political tradition, but making some limited democratic innovations—all while trying to maintain a delicate balance between national and state sovereignty. It was a complicated and highly controversial scheme.

IV. Ratifying the Constitution

Delegates to the Constitutional Convention assembled, argued, and finally agreed in this room, styled in the same manner it was during the Convention. Photograph of the Assembly Room, Independence Hall, Philadelphia, PA. Wikimedia.

The convention voted to send its proposed Constitution to Congress, which was then sitting in New York, with a cover letter from George Washington. The plan for adopting the new Constitution, however, required approval from special state ratification conventions, not just Congress. During the ratification process, critics of the Constitution organized to persuade voters in the different states to oppose it.

Importantly, the Constitutional Convention had voted down a proposal from Virginia’s George Mason, the author of Virginia’s state Declaration of Rights, for a national bill of rights. This omission became a rallying point for opponents of the document. Many of these “Anti-Federalists” argued that without such a guarantee of specific rights, American citizens risked losing their personal liberty to the powerful federal government. The pro-ratification “Federalists,” on the other hand, argued that including a bill of rights was not only redundant but dangerous; it could limit future citizens from adding new rights.10

Citizens debated the merits of the Constitution in newspaper articles, letters, sermons, and coffeehouse quarrels across America. Some of the most famous, and most important, arguments came from Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison in the Federalist Papers which were published in various New York newspapers in 1787 and 1788.11 The first crucial vote came at the beginning of 1788 in Massachusetts. At first, the Anti-Federalists at the Massachusetts ratifying convention probably had the upper hand, but after weeks of debate, enough delegates changed their votes to narrowly approve the Constitution. But they also approved a number of proposed amendments, which were to be submitted to the first Congress. This pattern—ratifying the Constitution but attaching proposed amendments—was followed by other state conventions.

The most high-profile convention was held in Richmond, Virginia, in June 1788, when Federalists like James Madison, Edmund Randolph, and John Marshall squared off against equally influential Anti-Federalists like Patrick Henry and George Mason. Virginia was America’s most populous state, it had produced some of the country’s highest-profile leaders, and the success of the new government rested upon its cooperation. After nearly a month of debate, Virginia voted 89 to 79 in favor of ratification.12

On July 2, 1788, Congress announced that a majority of states had ratified the Constitution and that the document was now in effect. Yet this did not mean the debates were over. North Carolina, New York, and Rhode Island had not completed their ratification conventions, and Anti-Federalists still argued that the Constitution would lead to tyranny. The New York convention would ratify the Constitution by just three votes, and finally Rhode Island would ratify it by two votes—a full year after George Washington was inaugurated as president.

V. Rights and Compromises

Although debates continued, Washington’s election as president cemented the Constitution’s authority. By 1793, the term “Anti-Federalist” would be essentially meaningless. Yet the debates produced a piece of the Constitution that seems irreplaceable today. Ten amendments were added in 1791. Together, they constitute the Bill of Rights. James Madison, against his original wishes, supported these amendments as an act of political compromise and necessity. He had won election to the House of Representatives only by promising his Virginia constituents such a list of rights.

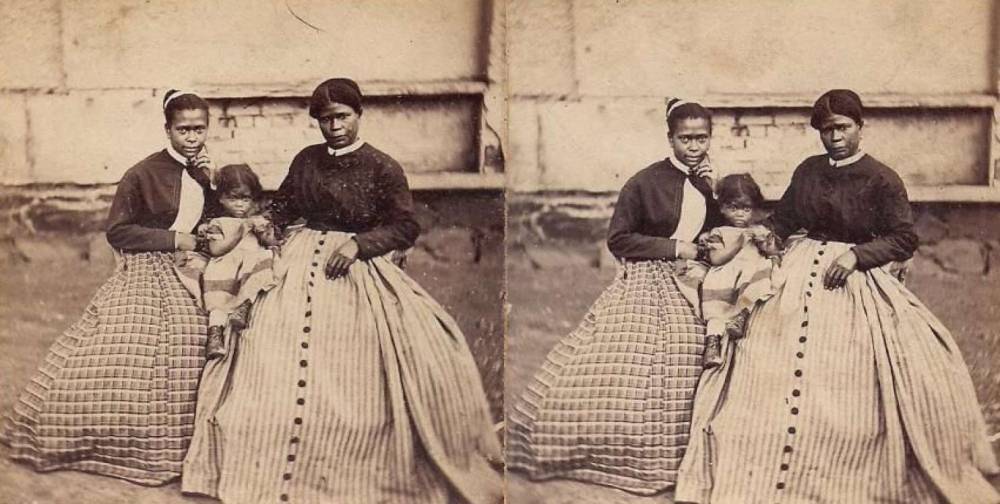

There was much the Bill of Rights did not cover. Women found no special protections or guarantee of a voice in government. Many states would continue to restrict voting only to men who owned significant amounts of property. And slavery not only continued to exist; it was condoned and protected by the Constitution.

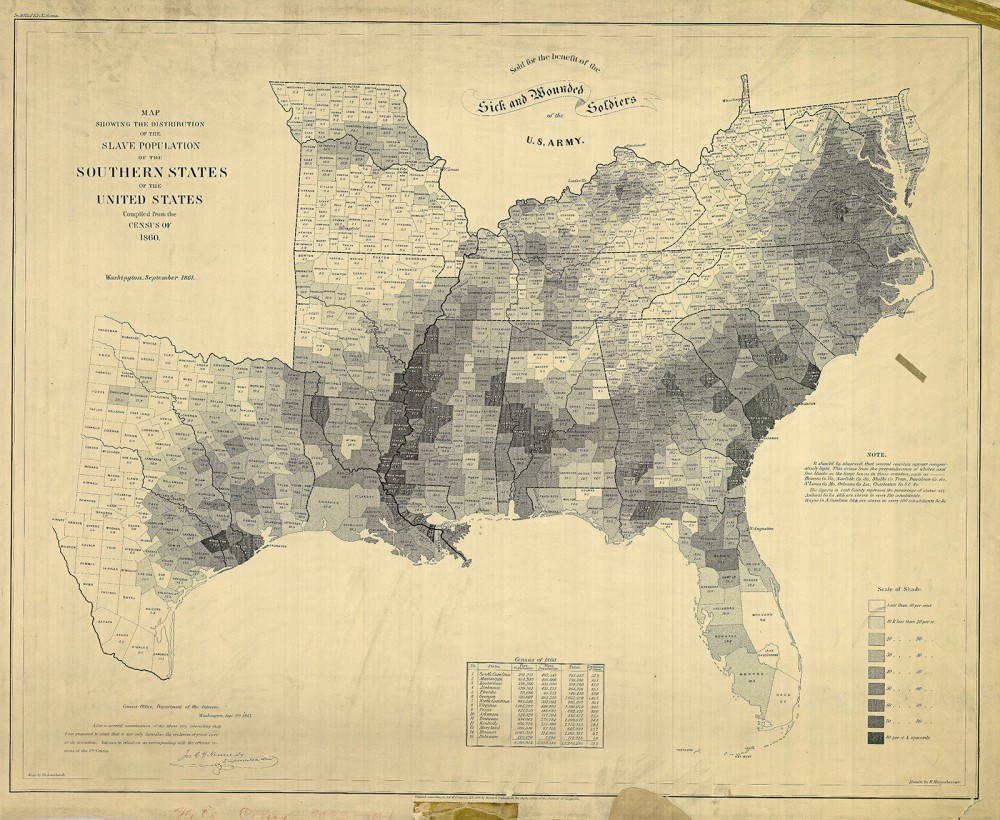

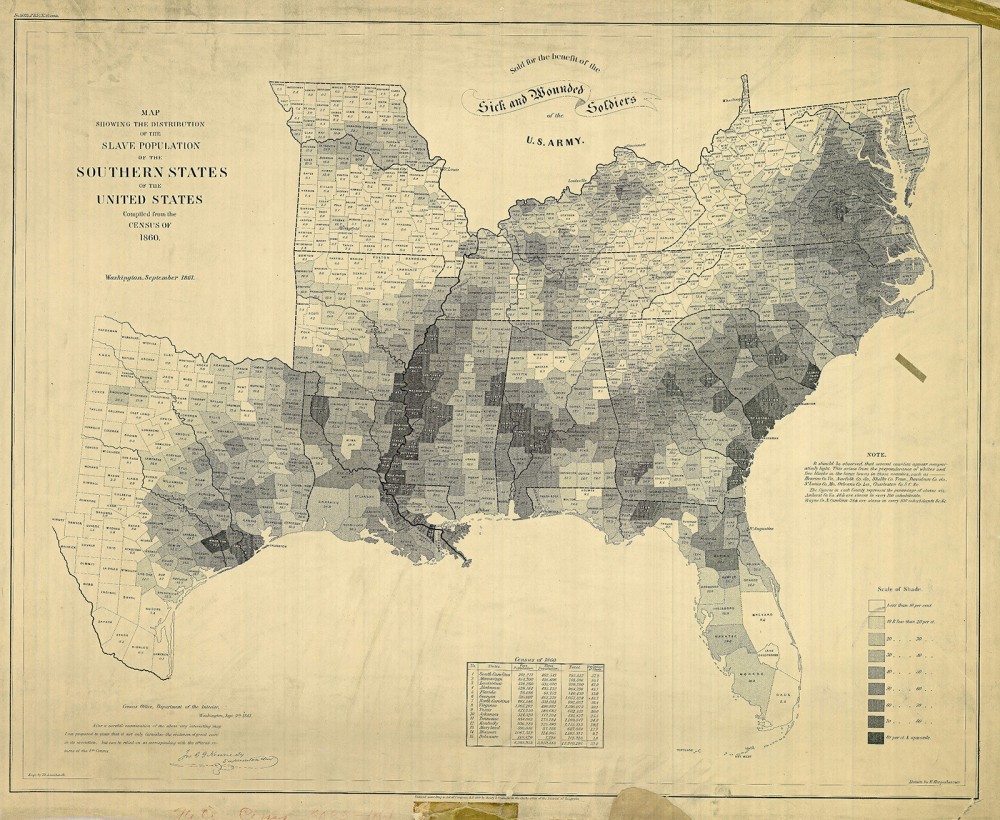

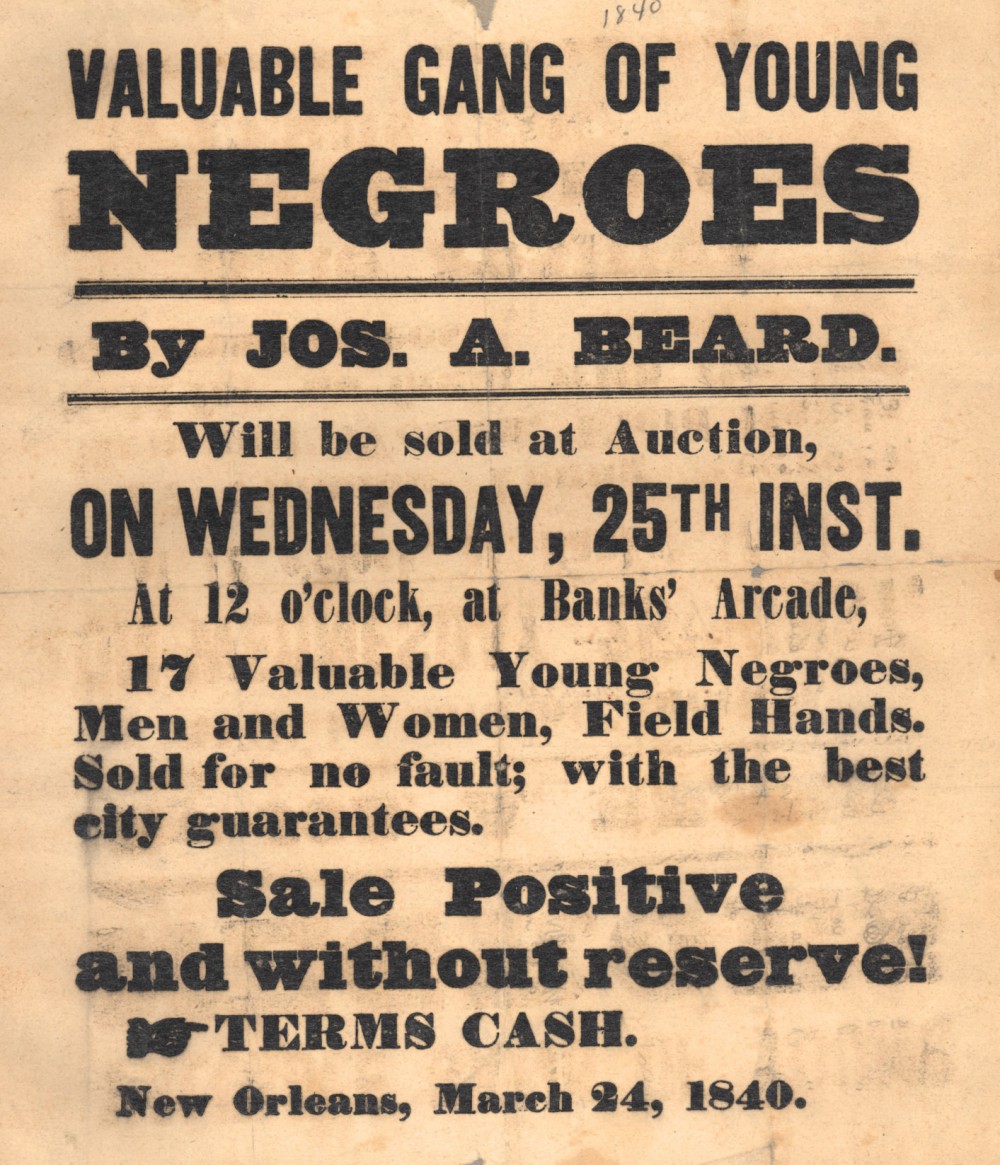

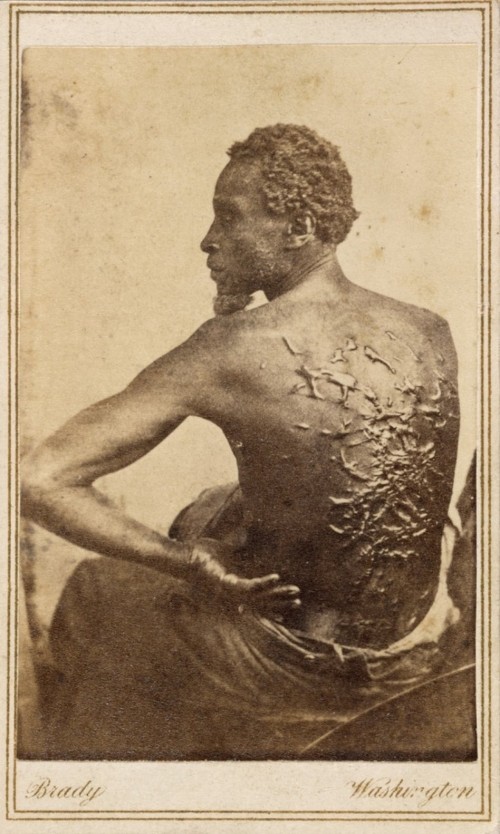

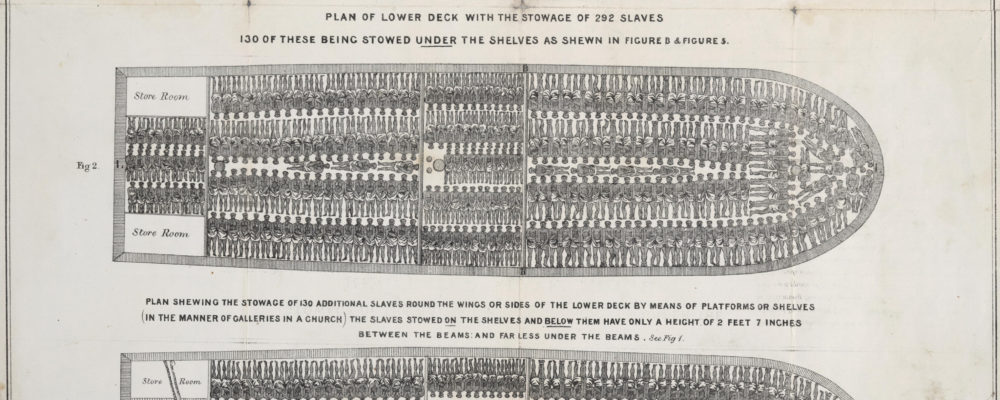

Of all the compromises that formed the Constitution, perhaps none would be more important than the compromise over the slave trade. Americans generally perceived the trans-Atlantic slave trade as more violent and immoral than slavery itself. Many Northerners opposed it on moral grounds. But they also understood that letting Southern states import more Africans would increase their political power. The Constitution counted each enslaved individual as three-fifths of a person for purposes of representation, so in districts with many slaves, the white voters had extra influence. On the other hand, the states of the Upper South also welcomed a ban on the Atlantic trade because they already had a surplus of slaves. Banning importation meant slaveowners in Virginia and Maryland could get higher prices when they sold their slaves to states like South Carolina and Georgia that were dependent upon a continued slave trade.

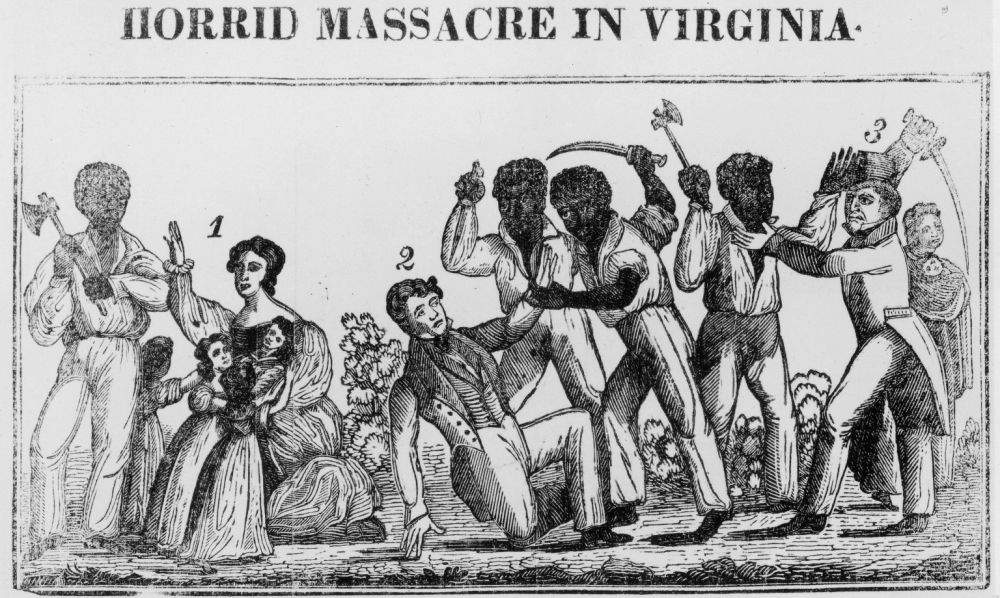

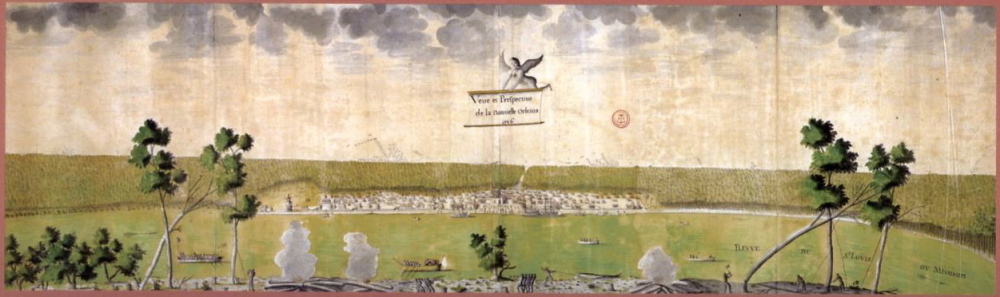

New England and the Deep South agreed to what was called a “dirty compromise” at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. New Englanders agreed to include a constitutional provision that protected the foreign slave trade for twenty years; in exchange, South Carolina and Georgia delegates had agreed to support a constitutional clause that made it easier for Congress to pass commercial legislation. As a result, the Atlantic slave trade resumed until 1808 when it was outlawed for three reasons. First, Britain was also in the process of outlawing the slave trade in 1807, and the United States did not want to concede any moral high ground to its rival. Second, the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), a successful slave revolt against French colonial rule in the West Indies, had changed the stakes in the debate. The image of thousands of armed black revolutionaries terrified white Americans. Third, the Haitian Revolution had ended France’s plans to expand its presence in the Americas, so in 1803, the United States had purchased the Louisiana Territory from the French at a fire-sale price. This massive new territory, which had doubled the size of the United States, had put the question of slavery’s expansion at the top of the national agenda. Many white Americans, including President Thomas Jefferson, thought that ending the external slave trade and dispersing the domestic slave population would keep the United States a white man’s republic and perhaps even lead to the disappearance of slavery.

The ban on the slave trade, however, lacked effective enforcement measures and funding. Moreover, instead of freeing illegally imported Africans, the act left their fate to the individual states, and many of those states simply sold intercepted slaves at auction. Thus, the ban preserved the logic of property ownership in human beings. The new federal government protected slavery as much as it expanded democratic rights and privileges for white men.13

VI. Hamilton’s Financial System

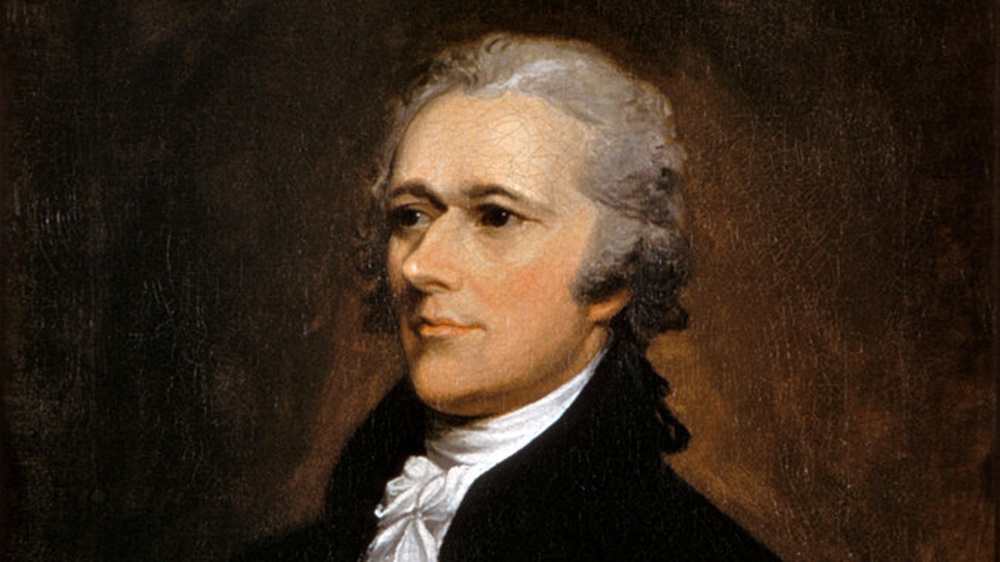

Alexander Hamilton saw America’s future as a metropolitan, commercial, industrial society, in contrast to Thomas Jefferson’s nation of small farmers. While both men had the ear of President Washington, Hamilton’s vision proved most appealing and enduring. John Trumbull, Portrait of Alexander Hamilton, 1806. Wikimedia.

President George Washington’s cabinet choices reflected continuing political tensions over the size and power of the federal government. The Vice President was John Adams, and Washington chose Alexander Hamilton to be his Secretary of the Treasury. Both men wanted an active government that would promote prosperity by supporting American industry. However, Washington chose Thomas Jefferson to be his Secretary of State, and Jefferson was committed to restricting federal power and preserving an economy based on agriculture. Almost from the beginning, Washington struggled to reconcile the “Federalist” and “Republican” (or Democratic-Republican) factions within his own administration.14

Alexander Hamilton believed that self-interest was the “most powerful incentive of human actions.” Self-interest drove humans to accumulate property, and that effort created commerce and industry. According to Hamilton, government had important roles to play in this process. First, the state should protect private property from theft. Second, according to Hamilton, the state should use human “passions” and “make them subservient to the public good.”15 In other words, a wise government would harness its citizens’ desire for property so that both private individuals and the state would benefit.

Hamilton, like many of his contemporary statesmen, did not believe the state should ensure an equal distribution of property. Inequality was understood as “the great & fundamental distinction in Society,” and Hamilton saw no reason this should change. Instead, Hamilton wanted to tie the economic interests of wealthy Americans, or “monied men,” to the federal government’s financial health. If the rich needed the government, then they would direct their energies to making sure it remained solvent.16

Hamilton, therefore, believed that the federal government must be “a Repository of the Rights of the wealthy.”17 As the nation’s first secretary of the treasury, he proposed an ambitious financial plan to achieve just that.

The first part of Hamilton’s plan involved federal “assumption” of state debts, which were mostly left over from the Revolutionary War. The federal government would assume responsibility for the states’ unpaid debts, which totaled about $25 million. Second, Hamilton wanted Congress to create a bank—a Bank of the United States.

The goal of these proposals was to link federal power and the country’s economic vitality. Under the assumption proposal, the states’ creditors (people who owned state bonds or promissory notes) would turn their old notes into the Treasury and receive new federal notes of the same face value. Hamilton foresaw that these bonds would circulate like money, acting as “an engine of business, and instrument of industry and commerce.”18 This part of his plan, however, was controversial for two reasons.

First, many taxpayers objected to paying the full face value on old notes, which had fallen in market value. Often the current holders had purchased them from the original creditors for pennies on the dollar. To pay them at full face value, therefore, would mean rewarding speculators at taxpayer expense. Hamilton countered that government debts must be honored in full, or else citizens would lose all trust in the government. Second, many southerners objected that they had already paid their outstanding state debts, so federal assumption would mean forcing them to pay again for the debts of New Englanders. Nevertheless, President Washington and Congress both accepted Hamilton’s argument. By the end of 1794, 98 percent of the country’s domestic debt had been converted into new federal bonds.19

Hamilton’s plan for a Bank of the United States, similarly, won congressional approval despite strong opposition. Thomas Jefferson and other Republicans argued that the plan was unconstitutional; the Constitution did not authorize Congress to create a bank. Hamilton, however, argued that the bank was not only constitutional but also important for the country’s prosperity. The Bank of the United States would fulfill several needs. It would act as a convenient depository for federal funds. It would print paper banknotes backed by specie (gold or silver). Its agents would also help control inflation by periodically taking state bank notes to their banks of origin and demanding specie in exchange, limiting the amount of notes the state banks printed. Furthermore, it would give wealthy people a vested interest in the federal government’s finances. The government would control just twenty percent of the bank’s stock; the other eighty percent would be owned by private investors. Thus, an “intimate connexion” between the government and wealthy men would benefit both, and this connection would promote American commerce.

In 1791, therefore, Congress approved a twenty-year charter for the Bank of the United States. The bank’s stocks, together with federal bonds, created over $70 million in new financial instruments. These spurred the formation of securities markets, which allowed the federal government to borrow more money and underwrote the rapid spread of state-charted banks and other private business corporations in the 1790s. For Federalists, this was one of the major purposes of the federal government. For opponents who wanted a more limited role for industry, however, or who lived on the frontier and lacked access to capital, Hamilton’s system seemed to reinforce class boundaries and give the rich inordinate power over the federal government.

Hamilton’s plan, furthermore, had another highly controversial element. In order to pay what it owed on the new bonds, the federal government needed reliable sources of tax revenue. In 1791, Hamilton proposed a federal excise tax on the production, sale, and consumption of a number of goods, including whiskey.

VII. The Whiskey Rebellion and Jay’s Treaty

Grain was the most valuable cash crop for many American farmers. In the West, selling grain to a local distillery for alcohol production was typically more profitable than shipping it over the Appalachians to eastern markets. Hamilton’s whiskey tax thus placed a special burden on western farmers. It seemed to divide the young republic in half—geographically between the East and West, economically between merchants and farmers, and culturally between cities and the countryside.

In the fall of 1761, sixteen men in western Pennsylvania, disguised in women’s clothes, assaulted a tax collector named Robert Johnson. They tarred and feathered him, and the local deputy marshals seeking justice met similar fates. They were robbed and beaten, whipped and flogged, tarred and feathered, and tied up and left for dead. The rebel farmers also adopted other protest methods from the Revolution and Shays’ Rebellion, writing local petitions and erecting liberty poles. For the next two years, tax collections in the region dwindled.

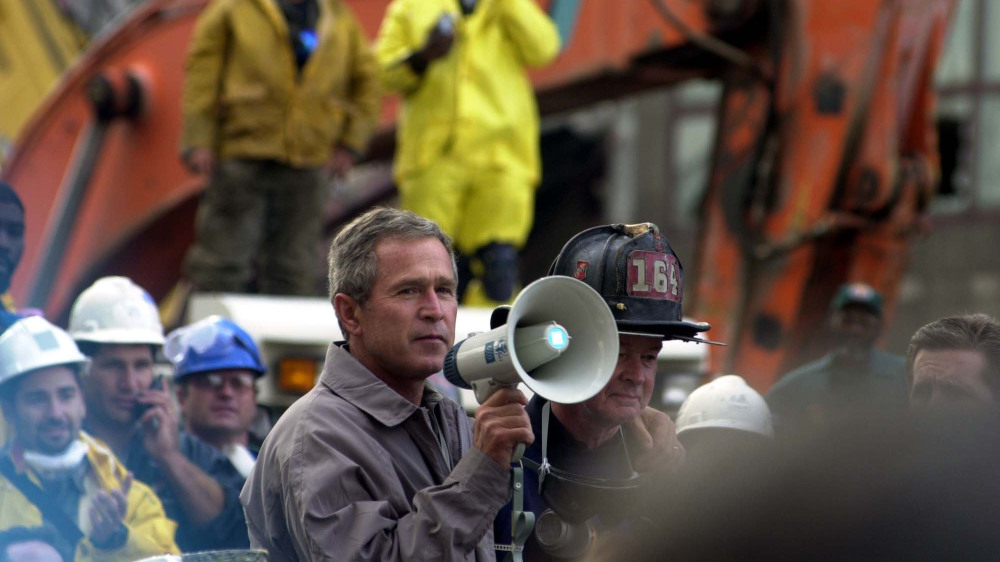

Then, in July 1794, groups of armed farmers attacked federal marshals and tax collectors, burning down at least two tax collectors’ homes. At the end of the month, an armed force of about 7,000, led by the radical attorney David Bradford, robbed the U.S. mail and gathered about eight miles east of Pittsburgh. President Washington responded quickly.

First, Washington dispatched a committee of three distinguished Pennsylvanians to meet with the rebels and try to bring about a peaceful resolution. Meanwhile, he gathered an army of thirteen thousand militiamen in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. On September 19, Washington became the only sitting president to lead troops in the field, though he quickly turned over the army to the command of Henry Lee, a Revolutionary hero and the current governor of Virginia.

As the federal army moved westward, the farmers scattered. Hoping to make a dramatic display of federal authority, Alexander Hamilton oversaw the arrest and trial of a number of rebels. Many were released due to lack of evidence, and most of those who remained, including two men sentenced to death for treason, were soon pardoned by the president. The Whiskey Rebellion had shown that the federal government was capable of quelling internal unrest. But it also demonstrated that some citizens, especially poor westerners, viewed it as their enemy.20

Around the same time, another national issue also aroused fierce protest. Along with his vision of a strong financial system, Hamilton also had a vision of a nation busily engaged in foreign trade. In his mind, that meant pursuing a friendly relationship with one nation in particular: Great Britain.

America’s relationship with Britain since the end of the Revolution had been tense, partly because of warfare between the British and French. Their naval war threatened American shipping, and the “impressment” of men into Britain’s navy terrorized American sailors. American trade could be risky and expensive, and impressment threatened seafaring families. Nevertheless, President Washington was conscious of American weakness and was determined not to take sides. In April 1793, he officially declared that the United States would remain neutral.21 With his blessing, Hamilton’s political ally John Jay, who was currently serving as chief justice of the Supreme Court, sailed to London to negotiate a treaty that would satisfy both Britain and the United States.

Jefferson and Madison strongly opposed these negotiations. They mistrusted Britain and saw the treaty as the American state favoring Britain over France. The French had recently overthrown their own monarchy, and Republicans thought the United States should be glad to have the friendship of a new revolutionary state. They also suspected that a treaty with Britain would favor northern merchants and manufacturers over the agricultural South.

In November 1794, despite their misgivings, John Jay signed a “treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation” with the British. Jay’s Treaty, as it was commonly called, required Britain to abandon its military positions in the Northwest Territory (especially Fort Detroit, Fort Mackinac, and Fort Niagara) by 1796. Britain also agreed to compensate American merchants for their losses. The United States, in return, agreed to treat Britain as its most prized trade partner, which meant tacitly supporting Britain in its current conflict with France. Unfortunately, Jay had failed to secure an end to impressment.22

For Federalists, this treaty was a significant accomplishment. Jay’s Treaty gave the United States, a relatively weak power, the ability to stay officially neutral in European wars, and it preserved American prosperity by protecting trade. For Jefferson’s Republicans, however, the treaty was proof of Federalist treachery. The Federalists had sided with a monarchy against a republic, and they had submitted to British influence in American affairs without even ending impressment. In Congress, debate over the treaty transformed the Federalists and Republicans from temporary factions into two distinct (though still loosely organized) political parties.

VIII. The French Revolution and the Limits of Liberty

The mounting body count of the French Revolution included that of the Queen and King, who were beheaded in a public ceremony in early 1793, as depicted in the engraving. While Americans disdained the concept of monarchy, the execution of King Louis XVI was regarded by many Americans as an abomination, an indication of the chaos and savagery reigning in France at the time. Charles Monnet (artist), Antoine-Jean Duclos and Isidore-Stanislas Helman (engravers), “Day of 21 January 1793 the death of Louis Capet on the Place de la Révolution,” 1794. Wikimedia.

In part, the Federalists were turning toward Britain because they feared the most radical forms of democratic thought. In the wake of Shays’ Rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion, and other internal protests, Federalists sought to preserve social stability. The course of the French Revolution seemed to justify their concerns.

In 1789, news had arrived in America that the French had revolted against their king. Most Americans imagined that liberty was spreading from America to Europe, carried there by the returning French heroes who had taken part in the American Revolution.

Initially, nearly all Americans had praised the French Revolution. Towns all over the country hosted speeches and parades on July 14 to commemorate the day it began. Women had worn neoclassical dress to honor republican principles, and men had pinned revolutionary cockades to their hats. John Randolph, a Virginia planter, named two of his favorite horses “Jacobin” and “Sans-Culotte” after French revolutionary factions.23

In April 1793, a new French ambassador, “Citizen” Edmond-Charles Genêt, arrived in the United States. During his tour of several cities, Americans greeted him with wild enthusiasm. Citizen Genêt encouraged Americans to act against Spain, a British ally, by attacking its colonies of Florida and Louisiana. When President Washington refused, Genêt threatened to appeal to the American people directly. In response, Washington demanded that France recall its diplomat. In the meantime, however, Genêt’s faction had fallen from power in France. Knowing that a return home might cost him his head, he decided to remain in America.

Genêt’s intuition was correct. A radical coalition of revolutionaries had seized power in France. They initiated a bloody purge of their enemies, the “Reign of Terror.” As Americans learned about Genêt’s impropriety and the mounting body count in France, many began to have second thoughts about the French Revolution.

Americans who feared that the French Revolution was spiraling out of control tended to become Federalists. Those who remained hopeful about the revolution tended to become Republicans. Not deterred by the violence, Thomas Jefferson declared that he would rather see “half the earth desolated” than see the French Revolution fail. “Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country, and left free,” he wrote, “it would be better than as it now is.”24 Meanwhile, the Federalists sought closer ties with Britain.

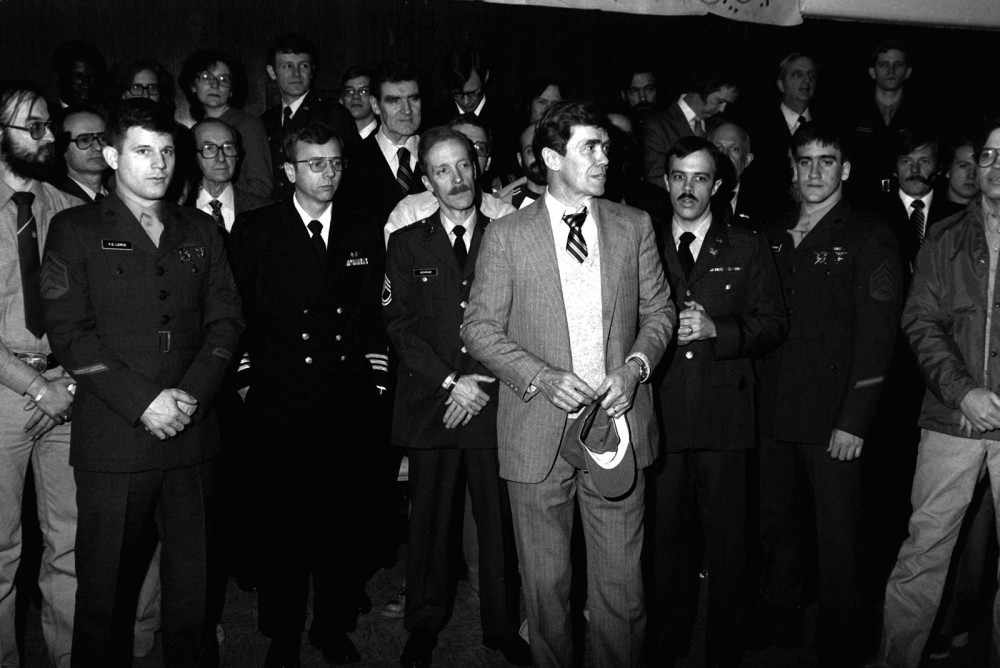

Despite the political rancor, in late 1796 there came one sign of hope: the United States peacefully elected a new president. For now, as Washington stepped down and executive power changed hands, the country did not descend into the anarchy that many leaders feared.

The new president was John Adams, Washington’s vice president. Adams was less beloved than the old general, and he governed a deeply divided nation. The foreign crisis also presented him with a major test.

In response to Jay’s Treaty, the French government authorized its vessels to attack American shipping. To resolve this, President Adams sent envoys to France in 1797. The French insulted these diplomats. Some officials, whom the Americans code-named “X,” “Y,” and “Z” in their correspondence, hinted that negotiations could begin only after the Americans offered a bribe. When the story became public, this “X.Y.Z. Affair” infuriated American citizens. Dozens of towns wrote addresses to President Adams, pledging him their support against France. Many people seemed eager for war. “Millions for defense,” toasted South Carolina representative Robert Goodloe Harper, “but not one cent for tribute.”25

By 1798, the people of Charleston watched the ocean’s horizon apprehensively because they feared the arrival of the French navy at any moment. Many people now worried that the same ships that had aided Americans during the Revolutionary War might discharge an invasion force on their shores. Some southerners were sure that this force would consist of black troops from France’s Caribbean colonies, who would attack the southern states and cause their slaves to revolt. Many Americans also worried that France had covert agents in the country. In the streets of Charleston, armed bands of young men searched for French disorganizers. Even the little children prepared for the looming conflict by fighting with sticks.26

Meanwhile, during the crisis, New Englanders were some of the most outspoken opponents of France. In 1798, they found a new reason for Francophobia. An influential Massachusetts minister, Jedidiah Morse, announced to his congregation that the French Revolution had been hatched in a conspiracy led by a mysterious anti-Christian organization called the Illuminati. The story was a hoax, but rumors of Illuminati infiltration spread throughout New England like wildfire, adding a new dimension to the foreign threat.27

Against this backdrop of fear, the French “Quasi-War,” as it would come to be known, was fought on the Atlantic, mostly between French naval vessels and American merchant ships. During this crisis, however, anxiety about foreign agents ran high, and members of Congress took action to prevent internal subversion. The most controversial of these steps were the Alien and Sedition Acts. These two laws, passed in 1798, were intended to prevent French agents and sympathizers from compromising America’s resistance, but they also attacked Americans who criticized the President and the Federalist Party.

The Alien Act allowed the federal government to deport foreign nationals, or “aliens,” who seemed to pose a national security threat. Even more dramatically, the Sedition Act allowed the government to prosecute anyone found to be speaking or publishing “false, scandalous, and malicious writing” against the government.28

These laws were not simply brought on by war hysteria. They reflected common assumptions about the nature of the American Revolution and the limits of liberty. In fact, most of the advocates for the Constitution and First Amendment accepted that free speech simply meant a lack of prior censorship or restraint, not a guarantee against punishment. According to this logic, “licentious” or unruly speech made society less free, not more. James Wilson, one of the principal architects of the Constitution, argued that “every author is responsible when he attacks the security or welfare of the government.”29

In 1798, most Federalists were inclined to agree. Under the terms of the Sedition Act, they indicted and prosecuted several Republican printers—and even a Republican congressman who had criticized President Adams. Meanwhile, although the Adams administration never enforced the Alien Act, its passage was enough to convince some foreign nationals to leave the country. For the president and most other Federalists, the Alien and Sedition Acts represented a continuation of a conservative rather than radical American Revolution.

However, the Alien and Sedition Acts caused a backlash in two ways. First, shocked opponents articulated a new and expansive vision for liberty. The New York lawyer Tunis Wortman, for example, demanded an “absolute independence” of the press.30 Likewise, the Virginia judge George Hay called for “any publication whatever criminal” to be exempt from legal punishment.31 Many Americans began to argue that free speech meant the ability to say virtually anything without fear of prosecution.

Second, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson helped organize opposition from state governments. Ironically, both of them had expressed support for the principle behind the Sedition Act in previous years. Jefferson, for example, had written to Madison in 1789 that the nation should punish citizens for speaking “false facts” that injured the country.32 Nevertheless, both men now opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts on constitutional grounds. In 1798, Jefferson made this point in a resolution adopted by the Kentucky state legislature. A short time later, the Virginia legislature adopted a similar document written by Madison.

The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions argued that the national government’s authority was limited to the powers expressly granted by the U.S. Constitution. More importantly, they asserted that the states could declare federal laws unconstitutional. For the time being, these resolutions were simply gestures of defiance. Their bold claim, however, would have important effects in later decades.

In just a few years, many Americans’ feelings towards France had changed dramatically. Far from rejoicing in the “light of freedom,” many Americans now feared the “contagion” of French-style liberty. Debates over the French Revolution in the 1790s gave Americans some of their earliest opportunities to articulate what it meant to be American. Did American national character rest on a radical and universal vision of human liberty? Or was America supposed to be essentially pious and traditional, an outgrowth of Great Britain? They couldn’t agree. It was upon this cracked foundation that many conflicts of the nineteenth century would rest.

IX. Religious Freedom

One reason the debates over the French Revolution became so heated was that Americans were unsure about their own religious future. The Illuminati scare of 1798 was just one manifestation of this fear. Across the United States, a slow but profound shift in attitudes toward religion and government began.

In 1776, none of the American state governments observed the separation of church and state. On the contrary, all thirteen states either had established, official, and tax-supported state churches, or at least required their officeholders to profess a certain faith. Most officials believed this was necessary to protect morality and social order. Over the next six decades, however, that changed. In 1833, the final state, Massachusetts, stopped supporting an official religious denomination. Historians call that gradual process “disestablishment.”

In many states, the process of disestablishment had started before the creation of the Constitution. South Carolina, for example, had been nominally Anglican before the Revolution, but it had dropped denominational restrictions in its 1778 constitution. Instead, it now allowed any church consisting of at least fifteen adult males to become “incorporated,” or recognized for tax purposes as a state-supported church. Churches needed only to agree to a set of basic Christian theological tenets, which were vague enough that most denominations could support them.33

Thus, South Carolina tried to balance religious freedom with the religious practice that was supposed to be necessary for social order. Officeholders were still expected to be Christians; their oaths were witnessed by God, they were compelled by their religious beliefs to tell the truth, and they were called to live according to the Bible. This list of minimal requirements came to define acceptable Christianity in many states. As new Christian denominations proliferated between 1780 and 1840, however, more and more Christians would fall outside of this definition. The new denominations would challenge the assumption that all Americans were Christians.

South Carolina continued its general establishment law until 1790, when a constitutional revision removed the establishment clause and religious restrictions on officeholders. Many other states, though, continued to support an established church well into the nineteenth century. The federal Constitution did not prevent this. The religious freedom clause in the Bill of Rights, during these decades, limited the federal government but not state governments. It was not until 1833 that a state supreme court decision ended Massachusetts’s support for the Congregational church.

Many political leaders, including Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, favored disestablishment because they saw the relationship between church and state as a tool of oppression. Jefferson proposed a Statute for Religious Freedom in the Virginia state assembly in 1779, but his bill failed in the overwhelmingly Anglican legislature. Madison proposed it again in 1785, and it defeated a rival bill that would have given equal revenue to all Protestant churches. Instead Virginia would not use public money to support religion. “The Religion then of every man,” Jefferson wrote, “must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate.”34

At the federal level, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 easily agreed that the national government should not have an official religion. This principle was upheld in 1791 when the First Amendment was ratified, with its guarantee of religious liberty. The limits of federal disestablishment, however, required discussion. The federal government, for example, supported Native American missionaries and Congressional chaplains. Well into the nineteenth century, debate raged over whether postal service should operate on Sundays, and whether non-Christians could act as witnesses in federal courts. Americans continued to struggle to understand what it meant for Congress not to “establish” a religion.

X. The Election of 1800

The year 1800 brought about a host of changes in government, in particular the first successful and peaceful transfer of power from one political party to another. But the year was important for another reason: the US Capitol in Washington, D.C. (pictured here in 1800) was finally opened to be occupied by the Congress, the Supreme Court, the Library of Congress, and the courts of the District of Columbia. William Russell Birch, A view of the Capitol of Washington before it was burnt down by the British, c. 1800. Wikimedia.

Meanwhile, the Sedition and Alien Acts expired in 1800 and 1801. They had been relatively ineffective at suppressing dissent. On the contrary, they were much more important for the loud reactions they had inspired. They had helped many Americans decide what they didn’t want from their national government.

By 1800, therefore, President Adams had lost the confidence of many Americans. They had let him know it. In 1798, for instance, he had issued a national thanksgiving proclamation. Instead of enjoying a day of celebration and thankfulness, Adams and his family had been forced by rioters to flee the capital city of Philadelphia until the day was over. Conversely, his prickly independence had also put him at odds with Alexander Hamilton, the leader of his own party, who offered him little support. After four years in office, Adams found himself widely reviled.

In the election of 1800, therefore, the Republicans defeated Adams in a bitter and complicated presidential race. During the election, one Federalist newspaper article predicted that a Republican victory would fill America with “murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest.”35 A Republican newspaper, on the other hand, flung sexual slurs against President Adams, saying he had “neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” Both sides predicted disaster and possibly war if the other should win.36

In the end, the contest came down to a tie between two Republicans, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia and Aaron Burr of New York, who each had 73 electoral votes. (Adams had 65.) Burr was supposed to be a candidate for vice president, not president, but under the Constitution’s original rules, a tie-breaking vote had to take place in the House of Representatives. It was controlled by Federalists bitter at Jefferson. House members voted dozens of times without breaking the tie. On the thirty-sixth ballot, Thomas Jefferson emerged victorious.

Republicans believed they had saved the United States from grave danger. An assembly of Republicans in New York City called the election a “bloodless revolution.” They thought of their victory as a revolution in part because the Constitution (and eighteenth-century political theory) made no provision for political parties. The Republicans thought they were fighting to rescue the country from an aristocratic takeover, not just taking part in a normal constitutional process.

“Providential Detection,” 1797 via American Antiquarian Society. This image attacks Jefferson’s support of the French Revolution and religious freedom. The letter, “To Mazzei,” refers to a 1796 correspondence that criticized the Federalists and, by association, President Washington.

In his first inaugural address, however, Thomas Jefferson offered an olive branch to the Federalists. He pledged to follow the will of the American majority, whom he believed were Republicans, but to respect the rights of the Federalist minority. His election set an important precedent. Adams accepted his electoral defeat and left the White House peacefully. “The revolution of 1800,” Jefferson would write years later, did for American principles what the Revolution of 1776 had done for its structure. But this time, the revolution was accomplished not “by the sword” but “by the rational and peaceable instrument of reform, the suffrage of the people.”37 Four years later, when the Twelfth Amendment changed the rules for presidential elections to prevent future deadlocks, it was designed to accommodate the way political parties worked.

Despite Adams’s and Jefferson’s attempts to tame party politics, though, the tension between federal power and the liberties of states and individuals would exist long into the nineteenth century. And while Jefferson’s administration attempted to decrease federal influence, Chief Justice John Marshall, an Adams appointee, worked to increase the authority of the Supreme Court. These competing agendas clashed most famously in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison, which Marshall used to establish a major precedent.

The Marbury case seemed insignificant at first. The night before leaving office in early 1801, Adams had appointed several men to serve as justices of the peace in Washington, D.C. By making these “midnight appointments,” Adams had sought to put Federalists into vacant positions at the last minute. Upon taking office, however, Jefferson and his secretary of state, James Madison, had refused to deliver the federal commissions to the men Adams had appointed. Several of the appointees, including William Marbury, sued the government, and the case was argued before the Supreme Court.

Marshall used Marbury’s case to make a clever ruling. On the issue of the commissions, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Jefferson administration. But Chief Justice Marshall went further in his decision, ruling that the Supreme Court reserved the right to decide whether an act of Congress violated the Constitution. In other words, the court assumed the power of judicial review. This was a major (and lasting) blow to the Republican agenda, especially after 1810, when the Supreme Court extended judicial review to state laws. Jefferson was particularly frustrated by the decision, arguing that the power of judicial review “would make the Judiciary a despotic branch.”38

XI. Conclusion

A grand debate over political power engulfed the young United States. The Constitution ensured that there would be a strong federal government capable of taxing, waging war, and making law, but it could never resolve the young nation’s many conflicting constituencies. The Whiskey Rebellion proved that the nation could stifle internal dissent but exposed a new threat to liberty. Hamilton’s banking system provided the nation with credit but also constrained frontier farmers. The Constitution’s guarantee of religious liberty conflicted with many popular prerogatives. Dissension only deepened, and as the 1790s progressed, Americans became bitterly divided over political parties and foreign wars.

During the ratification debates, Alexander Hamilton had written of the wonders of the Constitution. “A nation, without a national government,” he wrote, would be “an awful spectacle.” But, he added, “the establishment of a Constitution, in time of profound peace, by the voluntary consent of a whole people, is a prodigy,” a miracle that should be witnessed “with trembling anxiety.”39 Anti-Federalists had grave concerns about the Constitution, but even they could celebrate the idea of national unity. By 1795, even the staunchest critics would have grudgingly agreed with Hamilton’s convictions about the Constitution. Yet these same individuals could also take the cautions in Washington’s 1796 farewell address to heart. “There is an opinion,” Washington wrote, “that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the administration of the government and serve to keep alive the spirit of liberty.” This, he conceded, was probably true, but in a republic, he said, the danger was not too little partisanship, but too much. “A fire not to be quenched,” Washington warned, “it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.”40

For every parade, thanksgiving proclamation, or grand procession honoring the unity of the nation, there was also some political controversy reminding American citizens of how fragile their union was. And as party differences and regional quarrels tested the federal government, the new nation increasingly explored the limits of its democracy.

XII. Reference Material

This chapter was edited by Tara Strauch, with content contributions by Marco Basile, Nathaniel C. Green, Brenden Kennedy, Spencer McBride, Andrea Nero, Julie RichterCara Rogers, Tara Strauch, Michael Harrison Taylor, Jordan Taylor, Kevin Wisniewski, and Ben Wright.

Recommended citation: Marco Basile et al., “A New Nation,” Tara Strauch, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2016, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

Recommended Reading

- Allgor, Catherine. Parlor Politics: In which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000.

- Appleby, Joyce. Inheriting the Revolution: The First Generation of Americans. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2001.

- Bartolini-Tuazon, Kathleen. For Fear of an Elective King: George Washington and the Presidential Title Controversy of 1789. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014.

- Beeman, Richard, Stephen Botein, and Edward C. Carter II eds. Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and American National Identity. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1987.

- Bilder, Mary Sarah. Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Bouton, Terry. “A Road Closed: Rural Insurgency in Post-Independence Pennsylvania,” Journal of American History 87:3 (December 2000): 855-887.

- Cunningham, Noble E. The Jeffersonian Republicans: The Formation of Party Organization, 1789-1801. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1967.

- Dunn, Susan. Jefferson’s Second Revolution: The Election of 1800 and the Triumph of Republicanism. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004.

- Edling, Max. A Revolution in Favor of Government: Origins of the U.S. Constitution and the Making of the American State. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003

- Gordon-Reed, Annette. The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. New York: W. W. Norton, 2008.

- Halperin, Terri Diane. The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798: Testing the Constitution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

- Holton, Woody. Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution. 1st edition. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007.

- Kierner, Cynthia A. Martha Jefferson Randolph, Daughter of Monticello: Her Life and Times. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

- Maier, Pauline. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

- Papenfuse, Eric Robert. “Unleashing the ‘Wildness’: The Mobilization of Grassroots Antifederalism in Maryland,” Journal of the Early Republic 16:1 (Spring 1996): 73-106.

- Pasley, Jeffrey L. The First Presidential Contest: 1796 and the Founding of American Democracy. Lawrence: The University of Kansas Press, 2013.

- Smith-Rosenberg, Carroll. “Dis-Covering the Subject of the ‘Great Constitutional Discussion,’ 1786-1789,” Journal of American History 79:3 (December 1992): 841-873

- Taylor, Alan. William Cooper’s Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic. Reprint edition. New York: Vintage, 1996.

- Rakove, Jack N. Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution. New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

- Salmon, Marylynn. Women and the Law of Property in Early America. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

- Sharp, James Roger. American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Slaughter, Thomas P. The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Waldstreicher, David. In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes : The Making of American Nationalism, 1776-1820. Chapel Hill : Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Wood, Gordon. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Zagarri, Rosemarie. Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

Notes

- Francis Hopkinson, An Account of the Grand Federal Procession, Philadelphia, July 4, 1788, (Philadelphia: M. Carey, 1788). [↩]

- George Washington, Thanksgiving Proclamation, Oct. 3 1789; Fed. Reg., Presidential Proclamations, 1791 – 1991. [↩]

- Hampshire Gazette (CT), September 13, 1786. [↩]

- James Madison, The Federalist Papers, (New York: Signet Classics, 2003), no. 63. [↩]

- Woody Holton, Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007), 8-9. [↩]

- Virginia (Randolph) Plan as Amended (National Archives Microfilm Publication M866, 1 roll); The Official Records of the Constitutional Convention; Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, 1774-1789, Record Group 360; National Archives. [↩]

- Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (New York: Random House, 2009), 114. [↩]

- Herbert J. Storing, What the Anti-Federalists Were For: The Political Thought of the Opponents of the Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), 16. [↩]

- Ray Raphael, Mr. President: How and Why the Founders Created a Chief Executive (New York: Knopf, 2012), 50. [↩]

- David J. Siemers, Ratifying the Republic: Antifederalists and Federalists in Constitutional Time (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002). [↩]

- Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John Jay ,The Federalist Papers, Ian Shapiro, ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009). [↩]

- Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 225-237. [↩]

- David Waldstreicher, Slavery’s Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification (New York: Hill and Wang, 2009). [↩]

- Carson Holloway, Hamilton versus Jefferson in the Washington Administration: Completing the Founding or Betraying the Founding? (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015). [↩]

- Alexander Hamilton, The Works of Alexander Hamilton, Volume 1, Henry Cabot Lodge, ed. (New York: 1904), 70, 408. [↩]

- Alexander Hamilton, Report on Manufactures, (New York: 1791). [↩]

- James H. Hutson, ed., Supplement to Max Farrand’s the Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 119. [↩]

- Alexander Hamilton, Report on Manufactures, (New York: 1791). [↩]

- Richard Sylla, “National Foundations: Public Credit, the National Bank, and Securities Markets,” Founding Choices: American Economic Policy in the 1790s, Douglas A. Irwin, Richard Sylla, eds. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 68. [↩]

- Thomas P. Slaughter, The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986). [↩]

- “Proclamation of Neutrality, 1793,” A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents Prepared under the direction of the Joint Committee on printing, of the House and Senate Pursuant to an Act of the Fifty-Second Congress of the United States (New York : Bureau of National Literature, 1897). [↩]

- United States, Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, signed at London November 19, 1794, Submitted to the Senate June 8, Resolution of advice and consent, on condition, June 24, 1795. Ratified by the United States August 14, 1795. Ratified by Great Britain October 28, 1795. Ratifications exchanged at London October 28, 1795. Proclaimed February 29, 1796. [↩]

- Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Eugene D. Genovese, The Mind of the Master Class: History and Faith in the Southern Slaveholders Worldview (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 18. [↩]

- From Thomas Jefferson to William Short, 3 January 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-25-02-0016 [last update: 2015-06-29]). Source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 25, 1 January–10 May 1793, ed. John Catanzariti. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, pp. 14–17. [↩]

- Robert Goodloe Harper, June 18, 1798 quoted in the American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia), June 20, 1798. [↩]

- Robert J. Alderson Jr., This Bright Era of Happy Revolutions: French Consul Michel-Ange-Bernard Mangourit and International Republicanism in Charleston, 1792-1794 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2008). [↩]

- Rachel Hope Cleves, The Reigh of Terror in America: Visions of Violence from Anti-Jacobinism to Antislavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 47. [↩]

- The Alien Act, July 6, 1798 and An Act in Addition to the Act, Entitled “An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes Against the United States., July 14, 1798; Fifth Congress; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives. [↩]

- James Wilson, Congressional Debate December 1, 1787, in Jonathan Elliot ed. The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, (New York: 1888,) 2:448-50. [↩]

- Tunis Wortman, A Treatise Concerning Political Enquiry, and the Liberty of the Press (New York: 1800), 181. [↩]

- George Hay, An essay on the liberty of the press (Philadelphia: 1799), 43. [↩]

- Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, August 28, 1789, from The Works of Thomas Jefferson in Twelve Volumes. Federal Edition. Collected and Edited by Paul Leicester Ford. http://www.loc.gov/resource/mtj1.011_0853_0861 [↩]

- Francis Newton Thorpe, ed., The Federal and State Constitutions Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the States, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America Compiled and Edited Under the Act of Congress of June 30, 1906 (Washington, DC : Government Printing Office, 1909). [↩]

- Thomas Jefferson, An Act for Establishing Religious Freedom, 16 January 1786, Manuscript, Records of the General Assembly, Enrolled Bills, Record Group 78, Library of Virginia. [↩]

- Catherine Allgor, Parlor Politics: In which the Ladies of Washington Help Build a City and a Government (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000), 14. [↩]

- James T. Callender, The Prospect Before Us (Richmond: 1800). [↩]

- Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Spencer Roane, September 6, 1819, in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, 20 vols., ed. Albert Ellery Bergh (Washington, D.C.: 1903), 142. [↩]

- Harold H. Bruff, Untrodden Ground: How Presidents Interpret the Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 65. [↩]

- Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist Papers, (New York: Signet Classics, 2003), no. 85. [↩]

- George Washington, Farewell Address, Annals of Congress, 4th Congress, 2869-2870. [↩]

![The slave markets of the South varied in size and style, but the St. Louis Exchange in New Orleans was so frequently described it became a kind of representation for all southern slave markets. Indeed, the St. Louis Hotel rotunda was cemented in the literary imagination of nineteenth-century Americans after Harriet Beecher Stowe chose it as the site for the sale of Uncle Tom in her 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. After the ruin of the St. Clare plantation, Tom and his fellow slaves were suddenly property that had to be liquidated. Brought to New Orleans to be sold to the highest bidder, Tom found himself “[b]eneath a splendid dome” where “men of all nations” scurried about. J. M. Starling (engraver), "Sale of estates, pictures and slaves in the rotunda, New Orleans,” 1842. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sale_of_Estates_Pictures_and_Slaves_in_the_Rotunda_New_Orleans.jpg.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/Sale_of_Estates_Pictures_and_Slaves_in_the_Rotunda_New_Orleans-1000x732.jpg)

![Jesse Jackson was only the second African American to mount a national campaign for the presidency. His work as a civil rights activist and Baptist minister garnered him a significant following in the African American community, but never enough to secure the Democratic nomination. His Warren K. Leffler, “IVU w/ [i.e., interview with] Rev. Jesse Jackson,” July 1, 1983. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003688127/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/01277v-983x1500.jpg)

![Protestors hold signs that read "President Kennedy Be Careful," "Let the UN Handle the Cuban Crisis!," "Peace or Perish," and "[unclear] your responsibility and give us peace."](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/3c28465v-1000x1234.jpg)

![Photograph of James Meredith, accompanied by U.S. Marshalls, walking to class at the University of Mississippi in 1962. Meredith was the first African-American student admitted to the still segregated Ole Miss. Marion S. Trikosko, “Integration at Ole Miss[issippi] Univ[ersity],” 1962. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003688159/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/04292v-1000x653.jpg)

![Alabama governor George Wallace stands defiantly at the door of the University of Alabama, blocking the attempted integration of the school. Wallace was perhaps the most notoriously pro-segregation politician of the 1960s, proudly proclaiming in his 1963 inaugural address “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Warren K. Leffler, “[Governor George Wallace attempting to block integration at the University of Alabama],” June 11, 1963. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003688161/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/04294v1-1000x666.jpg)

![Like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois before them, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X represented two styles of racial uplift while maintaining the same general goal of ending racial discrimination. How they would get to that goal is where the men diverged. Marion S. Trikosko, “[Martin Luther King and Malcolm X waiting for press conference],” March 26, 1964. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92522562/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/3d01847v-1000x651.jpg)

![Photograph of the 1966 Rio Grande Valley Farm Workers March (“La Marcha”). Marchers hold the American flag, Texas flag, an image of the Virgin Mary, and signs that say "U.S. Democratic Principles Apply [unclear]," and "Justice for All Workers Now"](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/Untitled-11.jpg)