Introduction

Slavery had long divided the politics of the United States. In time, these divisions became both sectional and irreconcilable. As westward expansion continued, these fault lines grew unstable, particularly as the United States seized more lands from its war with Mexico. Violence in Kansas and in the United States capitol demonstrated how dangerous these divisions had become. As the country seemed to teeter ever closer to a full-throated endorsement of slavery, however, an antislavery coalition arose in the middle 1850s calling itself the Republican Party. Eager to cordon off slavery and confine it to where it already existed, the Republicans won the presidential election of 1860 and threw the nation on the path to war. By 1861 all bets were off, and the fate of slavery and the Union depended upon war. These sources offer glimpses into a nation on the verge of collapse.

Documents

Conflicts between the power of the federal government and states’ rights strained American politics throughout the antebellum era. During the 1840s and 1850s, the most consistent source of tension on the issue stemmed from northerners refusing to comply with fugitive slave laws. As early as the 1780s, Pennsylvania passed laws that made it illegal to take a Black person from the state for the purpose of enslaving them. In the majority opinion, excerpted here, Supreme Court justice Joseph Story decided that the national fugitive slave act overruled Pennsylvania’s law.

William Still was an African-American abolitionist who frequently risked his life to help freedom-seekers escape slavery. In these excerpts, Still offers the readers some of the letters sent to him from abolitionists and formerly enslaved persons. The passages shed light on family separation, the financial costs of the journey to freedom, and the logistics of the Underground Railroad.

In 1852 Harriet Beecher Stowe published her bestselling antislavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Sales for Uncle Tom’s Cabin were astronomical, eclipsed only by sales of the Bible. The book became a sensation and helped move antislavery into everyday conversation for many northerners. In this passage, a senator and his wife debate the Fugitive Slave Law.

Writer, activist, and teacher Charlotte Forten was born in Philadelphia in 1837 to a well-to-do African American family. Forten’s diary entries from 1854 illuminate sectional tensions, especially in her discussion of the trial of Anthony Burns, a fugitive from slavery. She also expressed frequent frustration over the racism she encountered in Boston.

After John Brown was arrested for his raid on Harpers Ferry, Lydia Maria Child wrote to the governor of Virginia requesting to visit Brown. Margaretta Mason of Virginia wrote a searing letter to Child attacking her for supporting a murder. Child responded, and the exchange of letters was published by the American Antislavery Society.

The 1860 Republican Party convention in Chicago created a platform that clearly opposed the expansion of slavery in the West and the reopening of the slave trade. However, nothing in the document claimed that the government had the power to eliminate slavery where it already existed. Controversies over slavery suffuse the platform, but maybe even more noticeable is the importance of the West to the Republican Party.

Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 contest on November 6 with just 40% of the popular vote and not a single southern vote in the Electoral College. Within days, southern states were organizing secession conventions. On December 20, South Carolina voted to secede, and issued its “Declaration of the Immediate Causes.”

Media

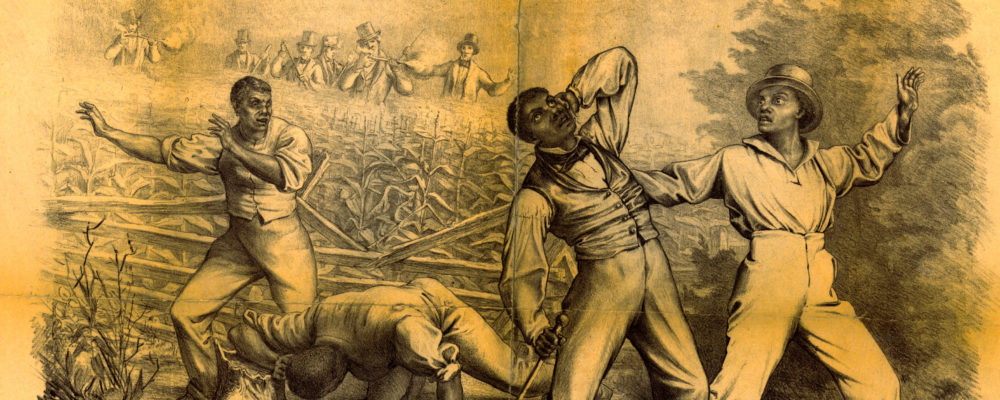

This lithograph imagines the consequences of the Fugitive Slave Act, part of the Compromise of 1850. Four well-dressed Black men are being hunted by a party of white men, seen in the background. There are a number of ambiguities in the image – are the Black men enslaved or free? Are they trying to escape or not? Where exactly are they? These ambiguities speak to the concerns many abolitionists had about the law, which required free citizens to return freedom-seekers to their enslavers.

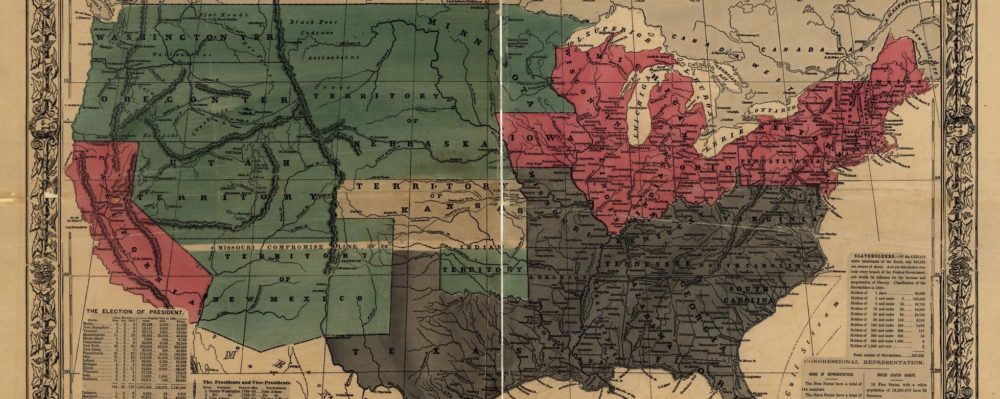

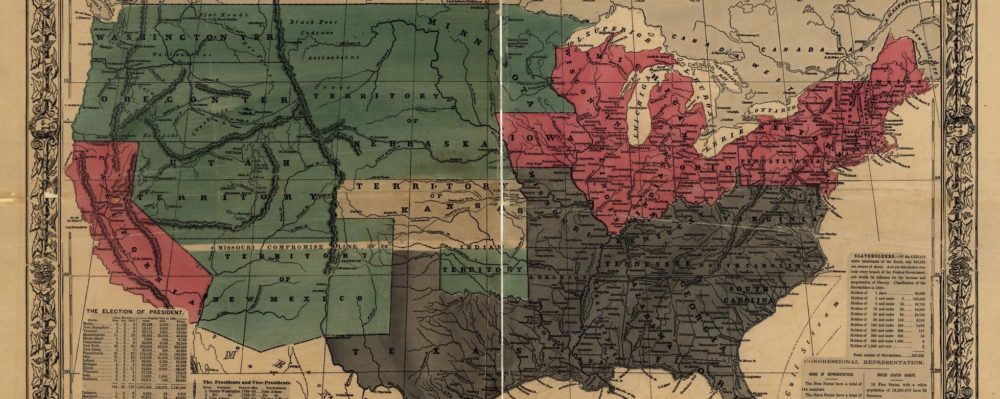

William C. Reynolds and J. C. Jones, “Reynolds’s political map of the United States, designed to exhibit the comparative area of the free and slave states and the territory open to slavery or freedom by the repeal of the Missouri Compromise,” 1856, via Library of Congress.