Introduction

Cotton created the antebellum South. The wildly profitable commodity opened a previously closed society to the grandeur, the profit, the exploitation, and the social dimensions of a larger, more connected, global community. Populations became more cosmopolitan, more educated, and wealthier. Systems of class—lower-, middle-, and upper-class communities—developed where they had never clearly existed. Ports that had once focused entirely on the importation of slaves, and shipped only regionally, became homes to daily and weekly shipping lines to New York City, Liverpool, Manchester, Le Havre, and Lisbon. The world was, slowly but surely, coming closer together; and the South was right in the middle. But slavery remained, and the internal slave trade rose as the 1860s approached. Political debate, race relations, and the burden of slavery continued beneath the roar of steamboats, counting houses, and the exchange of goods. Underneath it all, many questions remained—chief among them, what to do if slavery somehow came under threat. These sources offer perspectives on how southerners, enslaved and free, made meaning of their lives in an era of great change.

Documents

In August, 1831, Nat Turner led a group of enslaved and free Black men in a rebellion that killed over fifty white men, women, and children. Nat Turner understood his rebellion as an act of God. While he awaited trial, Turner spoke with the white attorney, Thomas Ruffin Gray, who wrote their conversations into the following document.

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in North Carolina. After escaping to New York, Jacobs eventually wrote a narrative of her enslavement under the pseudonym of Linda Brent. In this excerpt Jacobs explains her experience struggling with sexual assault from her enslaver.

Solomon Northup was a free Black man in New York who was captured and sold into slavery. After twelve years, he was rescued and returned to his family. Shortly thereafter, he published a narrative of his experiences as a slave. This excerpt describes the horrors he saw in a slave market.

As the nineteenth century progressed, some Americans shifted their understanding of slavery from a necessary evil to a positive good. George Fitzhugh offered one of the most consistent and sophisticated defenses of slavery. His study Sociology for the South attacked northern society as corrupt and slavery as a gentle system designed to “protect” the inferior Black race and promote social harmony.

The Market Revolution brought a hardening of gender roles in both the North and the South, but the South tended to hold more tightly to the expectation of “separate spheres.” In this sermon, Rev. Aldert Smedes of Raleigh, North Carolina, praises the virtues of women and explains the duties of a Christian woman.

The coexistence of brutal oppression and genuine affection was but one of many contradictions in the antebellum slave system. In this postwar reflection, Mary Polk Branch recalls her life as an enslaver. We see here how many white southerners justified the ownership of human beings, as well as an indication of the priorities and perspectives of enslaving women.

First published in London, Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter (1853) by William Wells Brown is considered the first novel by an African-American. Brown was born in slavery in Kentucky and escaped to freedom at the age of 20. Opening with the auction of Currer, the supposed mistress of Thomas Jefferson, and their two daughters, Clotel and Althesa. Jefferson indeed had a sexual relationship with an enslaved woman named Sally Hemmings, but this story does more to expose the horrifying realities of life under slavery than explain the particular experiences of Sally Hemmings and her children.

Media

The English painter Eyre Crowe traveled through the American South in the early 1850s. He was particularly shocked to see the horrors of a slave market where families were torn apart by sale. In this painting, Crowe depicts an enslaved man, several women, and children waiting to be sold at auction.

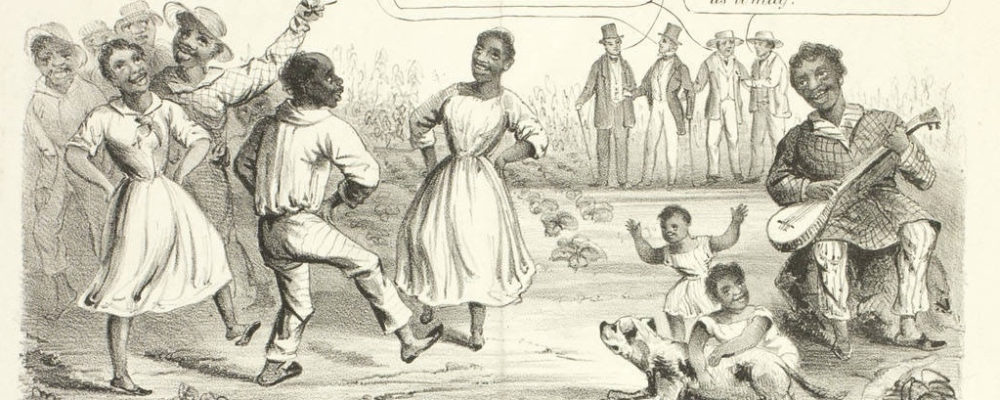

European alliances helped the American antislavery movement. But proslavery supporters also drew transatlantic comparisons. This proslavery image ignorantly portrays enslaved people who, according to white observers, were cheerful and pleased with their bondage. Proslavery advocates attempted to claim that English factory workers suffered a worse “slavery” than enslaved Africans and African Americans in the American South.