*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

On a sunny day in early March of 1921, Warren G. Harding took the oath to become the twenty-ninth President of the United States. He had won a landslide election by promising a “return to normalcy.” “Our supreme task is the resumption of our onward, normal way,” he declared in his inaugural address. Two months later, he said, “America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration.” The nation still reeled from the shock of World War I, the explosion of racial violence and political repression in 1919, and, bolstered by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, a lingering “Red Scare.”

More than 115,000 American soldiers had lost their lives in barely a year of fighting in Europe. Between 1918 and 1920, nearly 700,000 Americans died in a flu epidemic that hit nearly twenty percent of the American population. Waves of strikes hit soon after the war. Radicals bellowed. Anarchists and others sent more than thirty bombs through the mail on May 1, 1919. After war controls fell, the economy tanked and national unemployment hit twenty percent. Farmers’ bankruptcy rates, already egregious, now skyrocketed. Harding could hardly deliver the peace that he promised, but his message nevertheless resonated among a populace wracked by instability.

The 1920s would be anything but “normal.” The decade so reshaped American life that it came to be called by many names: the New Era, the Jazz Age, the Age of the Flapper, the Prosperity Decade, and, most commonly, the Roaring Twenties. The mass production and consumption of automobiles, household appliances, film, and radio fueled a new economy and new standards of living, new mass entertainment introduced talking films and jazz while sexual and social restraints loosened. BUt at the same time, many Americans turned their back on reform, denounced America’s shifting demographics, stifled immigration, retreated toward “old time religion,” and revived with millions of new members the Ku Klux Klan. Others, meanwhile, fought harder than ever for equal rights. Americans noted the appearance of “the New Woman” and “the New Negro.” Old immigrant communities that had predated the new immigration quotas clung to their cultures and their native faiths. The 1920s were a decade of conflict and tension. And whatever it was, it was not “normalcy.”

II. Republican White House, 1921-1933

To deliver on his promises of stability and prosperity, Harding signed legislation to restore a high protective tariff and dismantled the last wartime controls over industry. Meanwhile, the vestiges of America’s involvement in the First World War and its propaganda and suspicions of anything less than “100 percent American,” pushed Congress to address fears of immigration and foreign populations. A sour postwar economy led elites to raise the specter of the Russian Revolution and sideline not just the various American socialist and anarchist organizations, but nearly all union activism. During the 1920s, the labor movement suffered a sharp decline in memberships. Workers not only lost bargaining power, but also the support of courts, politicians, and, in large measure, the American public. ((David Montgomery, The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865-1925 (Cambridge University Press, 1988).))

Harding’s presidency, though, would go down in history as among the most corrupt. Many of Harding’s cabinet appointees, for instance, were individuals of true stature that answered to various American constituencies. For instance, Henry C. Wallace, the very vocal editor of Wallace’s Farmer and a well-known proponent of “scientific farming,” was made Secretary of Agriculture. Herbert Hoover, the popular head and administrator of the wartime Food Administration and a self-made millionaire, was made Secretary of Commerce. To satisfy business interests, the conservative businessmen Andrew Mellon became Secretary of the Treasury. Mostly, however, it was the appointing of friends and close supporters, dubbed “the Ohio gang,” that led to trouble. ((William E. Leuchtenburg, The Perils of Prosperity, 1914–1932 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993 [

Harding’s administration suffered a tremendous setback when several officials conspired to lease government land in Wyoming to oil companies in exchange for cash. Known as the Teapot Dome scandal (named after the nearby rock formation that resembled a teapot), Interior Secretary Albert Fall and Navy Secretary Edwin Denby were eventually convicted and sent to jail. Harding took vacation in the summer of 1923 so that he could think deeply on how to deal “with my God-damned friends”—it was his friends, and not his enemies, that kept him up walking the halls at nights. But then, on August of 1923, Harding died suddenly of a heart attack and Vice President Calvin Coolidge ascended to the highest office in the land. ((Robert K. Murray, The Harding Era: Warren G. Harding and His Administration (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1969.))

The son of a shopkeeper, Coolidge climbed the Republican ranks from city councilman to the Governor of Massachusetts. As president, Coolidge sought to remove the stain of scandal but he otherwise continued Harding’s economic approach, refusing to take actions in defense of workers or consumers against American business. “The chief business of the American people,” the new President stated, “is business.” One observer called Coolidge’s policy “active inactivity,” but Coolidge was not afraid of supporting business interests and wealthy Americans by lowering taxes or maintaining high tariff rates. Congress, for instance, had already begun to reduce taxes on the wealthy from wartime levels of sixty-six percent to twenty percent, which Coolidge championed. ((Leuchtenburg, Perils.))

While Coolidge supported business, other Americans continued their activism. The 1920s, for instance, represented a time of great activism among American women, who had won the vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920. Female voters, like their male counterparts, pursued many interests. Concerned about squalor, poverty, and domestic violence, women had already lent their efforts to prohibition, which went into effect under the Eighteenth Amendment in January 1920. After that point, alcohol could no longer be manufactured or sold. Other reformers urged government action to ameliorate high mortality rates among infants and children, to provide federal aid for education, and ensure peace and disarmament. Some activists advocated protective legislation for women and children, while Alice Paul and the National Women’s Party called for the elimination of all legal distinctions “on account of sex” through the proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which was introduced but defeated in Congress. ((Nancy Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987).))

![During the 1920s, the National Women’s Party fought for the rights of women beyond that of suffrage, which they had secured through the 19th Amendment in 1920. They organized private events, like the tea party pictured here, and public campaigning, such as the introduction of the Equal Rights Amendment to Congress, as they continued the struggle for equality. “Reception tea at the National Womens [i.e., Woman's] Party to Alice Brady, famous film star and one of the organizers of the party,” April 5, 1923. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/91705244/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/3c02300v-1000x795.jpg)

During the 1920s, the National Women’s Party fought for the rights of women beyond that of suffrage, which they had secured through the 19th Amendment in 1920. They organized private events, like the tea party pictured here, and public campaigning, such as the introduction of the Equal Rights Amendment to Congress, as they continued the struggle for equality. “Reception tea at the National Womens [i.e., Woman’s] Party to Alice Brady, famous film star and one of the organizers of the party,” April 5, 1923. Library of Congress.

III. Culture of Consumption

“Change is in the very air Americans breathe, and consumer changes are the very bricks out of which we are building our new kind of civilization,” announced marketing expert and home economist Christine Frederick in her influential 1929 monograph, Selling Mrs. Consumer. The book, which was based on one of the earliest surveys of American buying habits, advised manufacturers and advertisers how to capture the purchasing power of women, who, according to Frederick, accounted for 90% of household expenditures. Aside from granting advertisers insight into the psychology of the “average” consumer, Frederick’s text captured the tremendous social and economic transformations that had been wrought over the course of her lifetime. ((Christine Frederick, Selling Mrs. Consumer, (New York: The Business Bourse, 1929), 29.))

Indeed, the America of Frederick’s birth looked very different from the one she confronted in 1929. The consumer change she studied had resulted from the industrial expansion of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. With the discovery of new energy sources and manufacturing technologies, industrial output flooded the market with a range of consumer products such as ready-to-wear clothing to convenience foods to home appliances. By the end of the nineteenth century, output had risen so dramatically that many contemporaries feared supply had outpaced demand and that the nation would soon face the devastating financial consequences of overproduction. American businessmen attempted to avoid this catastrophe by developing new merchandising and marketing strategies that transformed distribution and stimulated a new culture of consumer desire. ((T.J. Jackson Lears, From Salvation to Self-Realization: Advertising and the Therapeutic Roots of the Consumer Culture, 1880-1930, in The Culture of Consumption: Critical Essays in American History, 1880-1980, edited by Richard Wightman Fox and T.J. Jackson Lears (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983), 1-38.))

The department store stood at the center of this early consumer revolution. By the 1880s, several large dry goods houses blossomed into modern retail department stores. These emporiums concentrated a broad array of goods under a single roof, allowing customers to purchase shirtwaists and gloves alongside toy trains and washbasins. To attract customers, department stores relied on more than variety. They also employed innovations in service—such as access to restaurants, writing rooms, and babysitting—and spectacle—such as elaborately decorated store windows, fashion shows, and interior merchandise displays. Marshall Field & Co. was among the most successful of these ventures. Located on State Street in Chicago, the company pioneered many of these strategies, including establishing a tearoom that provided refreshment to the well-heeled women shoppers that comprised the store’s clientele. Reflecting on the success of Field’s marketing techniques, Thomas W. Goodspeed, an early trustee of the University of Chicago wrote, “Perhaps the most notable of Mr. Field’s innovations was that he made a store in which it was a joy to buy.” ((Thomas W. Goodspeed, “Marshall Field,” University of Chicago Magazine, Vol. III (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1922), 48.))

The joy of buying infected a growing number of Americans in the early twentieth century as the rise of mail-order catalogs, mass-circulation magazines, and national branding further stoked consumer desire. The automobile industry also fostered the new culture of consumption by promoting the use of credit. By 1927, more than sixty percent of American automobiles were sold on credit, and installment purchasing was made available for nearly every other large consumer purchase. Spurred by access to easy credit, consumer expenditures for household appliances, for example, grew by more than 120 percent between 1919 and 1929. Henry Ford’s assembly line, which advanced production strategies practiced within countless industries, brought automobiles within the reach of middle-income Americans and fruther drove the spirit of consumerism. By 1925, Ford’s factories were turning out a Model-T every 10 seconds. The number of registered cars ballooned from just over nine million in 1920 to nearly twenty-seven million by the decade’s end. Americans owned more cars than Great Britain, Germany, France, and Italy combined. In the late 1920s, eighty percent of the world’s cars drove on American roads.

IV. Culture of Escape

As transformative as steam and iron had been in the previous century, gasoline and electricity—embodied most dramatically for many Americans in automobiles, film, and radio—propelled not only consumption, but also the famed popular culture in the 1920s. “We wish to escape,” wrote Edgar Burroughs, author of the Tarzan series. “The restrictions of manmade laws, and the inhibitions that society has placed upon us.” Burroughs authored a new Tarzan story nearly every year from 1914 until 1939. “We would each like to be Tarzan,” he said. “At least I would; I admit it.” Like many Americans in the 1920s, Burroughs sought to challenge and escape the constraints of a society that seemed more industrialized with each passing day. ((LeRoy Ashby, With Amusement for All: A History of American Popular Culture Since 1830 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006), 177.))

Just like Burroughs, Americans escaped with great speed. Whether through the automobile, Hollywood’s latest films, jazz records produced on Tin Pan Alley, or the hours spent listening to radio broadcasts of Jack Dempsey’s prizefights, the public wrapped itself in popular culture. One observer estimated that Americans belted out the silly musical hit “Yes, We Have No Bananas” more than “The Star Spangled Banner” and all the hymns in all the hymnals combined. ((Ibid., 183.))

As the automobile became more popular and more reliable, more people traveled more frequently and attempted greater distances. Women increasingly drove themselves to their own activities as well as those of their children. Vacationing Americans sped to Florida to escape northern winters. Young men and women fled the supervision of courtship, exchanging the staid parlor couch for sexual exploration in the backseat of a sedan. In order to serve and capture the growing number of drivers, Americans erected gas stations, diners, motels, and billboards along the roadside. Automobiles themselves became objects of entertainment: nearly one hundred thousand people gathered to watch drivers compete for the $50,000 prize of the Indianapolis 500.

The automobile changed American life forever. Rampant consumerism, the desire to travel, and the affordability of cars allowed greater numbers of Americans to purchase automobiles. This was possible only through innovations in automobile design and manufacturing led by Henry Ford in Detroit, Michigan. Ford was a lifelong inventor, creating his very first automobile – the quadricycle – in his home garage. From The Truth About Henry Ford by Sarah T. Bushnell, 1922. Wikimedia.

Meanwhile, the United States dominated the global film industry. By 1930, as movie-making became more expensive, a handful of film companies took control of the industry. Immigrants, mostly of Jewish heritage from Central and Eastern Europe, originally “invented Hollywood” because most turn-of-the-century middle and upper class Americans viewed cinema as lower-class entertainment. After their parents emigrated from Poland in 1876, Harry, Albert, Sam, and Jack Warner (who were given the name when an Ellis Island official could not understand their surname) founded Warner Bros. in 1918. Universal, Paramount, Columbia, and MGM were all founded by or led by Jewish executives. Aware of their social status as outsiders, these immigrants (or sons of immigrants) purposefully produced films that portrayed American values of opportunity, democracy, and freedom.

Not content with distributing thirty-minute films in nickelodeons, film moguls produced longer, higher-quality films and showed them in palatial theaters that attracted those who had previously shunned the film industry. But as filmmakers captured the middle and upper classes, they maintained working-class moviegoers by blending traditional and modern values. Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 epic The Ten Commandments depicted orgiastic revelry, for instance, while still managing to celebrate a biblical story. But what good was a silver screen in a dingy theater? Moguls and entrepreneurs soon constructed picture palaces. Samuel Rothafel’s Roxy Theater in New York held more than six thousand patrons who could be escorted by a uniformed usher past gardens and statues to their cushioned seat. In order to show The Jazz Singer (1927), the first movie with synchronized words and pictures, the Warners spent half a million to equip two theaters. “Sound is a passing fancy,” one MGM producer told his wife, but Warner Bros.’ assets, which increased from just $5,000,000 in 1925 to $230,000,000 in 1930, tell a different story. ((Ibid., 216.))

Americans fell in love with the movies. Whether it was the surroundings, the sound, or the production budgets, weekly movie attendance skyrocketed from sixteen million in 1912 to forty million in the early 1920s. Hungarian immigrant William Fox, founder of Fox Film Corporation, declared that “the motion picture is a distinctly American institution” because “the rich rub elbows with the poor” in movie theaters. With no seating restriction, the one-price admission was accessible for nearly all Americans (African Americans, however, were either excluded or segregated). Women represented more than sixty percent of moviegoers, packing theaters to see Mary Pickford, nicknamed “America’s Sweetheart,” who was earning one million dollars a year by 1920 through a combination of film and endorsements contracts. Pickford and other female stars popularized the “flapper,” a woman who favored short skirts, makeup, and cigarettes.

Mary Pickford’s film personas led the glamorous and lavish lifestyle that female movie-goers of the 1920s desired so much. Mary Pickford, 1920. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003666664.

As Americans went to the movies more and more, at home they had the radio. Italian scientist Guglielmo Marconi transmitted the first transatlantic wireless (radio) message in 1901, but radios in the home did not become available until around 1920, when they boomed across the country. Around half of American homes contained a radio by 1930. Radio stations brought entertainment directly into the living room through the sale of advertisements and sponsorships, from The Maxwell House Hour to the Lucky Strike Orchestra. Soap companies sponsored daytime drams so frequently that an entire genre—“soap operas”—was born, providing housewives with audio adventures that stood in stark contrast to common chores. Though radio stations were often under the control of corporations like the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) or the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), radio programs were less constrained by traditional boundaries in order to capture as wide an audience as possible, spreading popular culture on a national level.

Radio exposed Americans to a broad array of music. Jazz, a uniquely American musical style popularized by the African-American community in New Orleans, spread primarily through radio stations and records. The New York Times had ridiculed jazz as “savage” because of its racial heritage, but the music represented cultural independence to others. As Harlem-based musician William Dixon put it, “It did seem, to a little boy, that . . . white people really owned everything. But that wasn’t entirely true. They didn’t own the music that I played.” The fast-paced and spontaneity-laced tunes invited the listener to dance along. “When a good orchestra plays a ‘rag,’” dance instructor Vernon Castle recalled, “One has simply got to move.” Jazz became a national sensation, played and heard by whites and blacks both. Jewish Lithuanian-born singer Al Jolson—whose biography inspired The Jazz Singer and who played the film’s titular character—became the most popular singer in America. ((Ibid., 210.))

The 1920s also witnessed the maturation of professional sports. Play-by-play radio broadcasts of major collegiate and professional sporting events marked a new era for sports, despite the institutionalization of racial segregation in most. Suddenly, Jack Dempsey’s left crosses and right uppercuts could almost be felt in homes across the United States. Dempsey, who held the heavyweight championship for most of the decade, drew million-dollar gates and inaugurated “Dempseymania” in newspapers across the country. Red Grange, who carried the football with a similar recklessness, helped to popularize professional football, which was then in the shadow of the college game. Grange left the University of Illinois before graduating to join the Chicago Bears in 1925. “There had never been such evidence of public interest since our professional league began,” recalled Bears owner George Halas of Grange’s arrival. ((Ibid., 181.))

Perhaps no sports figure left a bigger mark than did Babe Ruth. Born George Herman Ruth, the “Sultan of Swat” grew up in an orphanage in Baltimore’s slums. Ruth’s emergence onto the national scene was much needed, as the baseball world had been rocked by the so-called black Sox scandal in which eight players allegedly agreed to throw the 1919 World Series. Ruth hit fifty-four home runs in 1920, which was more than any other team combined. Baseball writers called Ruth a superman, and more Americans could recognize Ruth than they could then-president Warren G. Harding.

After an era of destruction and doubt brought about by the First World War, Americans craved heroes that seemed to defy convention and break boundaries. Dempsey, Grange, and Ruth dominated their respective sport, but only Charles Lindbergh conquered the sky. On May 21, 1927, Lindbergh concluded the first ever non-stop solo flight from New York to Paris. Armed with only a few sandwiches, some bottles of water, paper maps, and a flashlight, Lindbergh successfully navigated over the Atlantic Ocean in thirty-three hours. Some historians have dubbed Lindbergh the “hero of the decade,” not only for his transatlantic journey, but because he helped to restore the faith of many Americans in individual effort and technological advancement. Devastated in war by machine guns, submarines, and chemical weapons, Lindbergh’s flight demonstrated that technology could inspire and accomplish great things. Outlook Magazine called Lindbergh “the heir of all that we like to think is best in America.” ((John W. Ward, “The Meaning of Lindbergh’s Flight, in Studies in American Culture: Dominant Ideas and Images, edited by Joseph J. Kwiat and Mary C. Turpie (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1960), 33.))

The decade’s popular culture seemed to revolve around escape. Coney Island in New York marked new amusements for young and old. Americans drove their sedans to massive theaters to enjoy major motion pictures. Radio towers broadcasted the bold new sound of jazz, the adventure of soap operas, and the feats of amazing athletes. Dempsey and Grange seemed bigger, stronger, and faster than any who dared to challenge them. Babe Ruth smashed home runs out of ball parks across the country. And Lindbergh escaped earth’s gravity and crossed entire ocean. Neither Dempsey nor Ruth nor Lindbergh made Americans forget the horrors of the First World War and the chaos that followed, but they made it seem as if the future would be that much brighter.

![Babe Ruth’s incredible talent attracted widespread attention to the sport of baseball, helping it become America’s favorite pastime. Ruth’s propensity to shatter records with the swing of his bat made him a national hero during a period when defying conventions was the popular thing to do. “[Babe Ruth, full-length portrait, standing, facing slightly left, in baseball uniform, holding baseball bat],” c. 1920. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92507380/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/3g07246v-500x632.jpg)

Babe Ruth’s incredible talent attracted widespread attention to the sport of baseball, helping it become America’s favorite pastime. Ruth’s propensity to shatter records with the swing of his bat made him a national hero during a period when defying conventions was the popular thing to do. “[Babe Ruth, full-length portrait, standing, facing slightly left, in baseball uniform, holding baseball bat],” c. 1920. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92507380/.

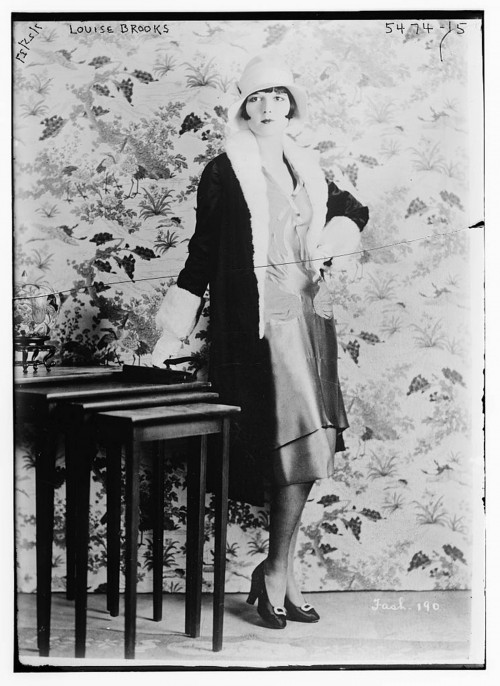

V. “The New Woman”

This “new breed” of women – known as the flapper – went against the gender proscriptions of the era, bobbing their hair, wearing short dresses, listening to jazz, and flouting social and sexual norms. While liberating in many ways, these behaviors also reinforced stereotypes of female carelessness and obsessive consumerism that would continue throughout the twentieth century. Bain News Service, “Louise Brooks,” undated. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2006007866/.

The rising emphasis on spending and accumulation nurtured a national ethos of materialism and individual pleasure. These impulses were embodied in the figure of the flapper, whose bobbed hair, short skirts, makeup, cigarettes, and carefree spirit captured the attention of American novelists such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis. Rejecting the old Victorian values of desexualized modesty and self-restraint, young “flappers” seized opportunities for the public coed pleasures offered by new commercial leisure institutions, such as dance halls, cabarets, and nickelodeons, not to mention the illicit blind tigers and speakeasies spawned by Prohibition. So doing, young American women had helped to usher in a new morality that permitted women greater independence, freedom of movement, and access to the delights of urban living. In the words of psychologist G. Stanley Hall, “She was out to see the world and, incidentally, be seen of it.”

Such sentiments were repeated in an oft-cited advertisement in a 1930 edition of the Chicago Tribune: “Today’s woman gets what she wants. The vote. Slim sheaths of silk to replace voluminous petticoats. Glassware in sapphire blue or glowing amber. The right to a career. Soap to match her bathroom’s color scheme.” As with so much else in 1920s, however, sex and gender were in many ways a study in contradictions. It was the decade of the “New Woman,” and one in which only 10% of married women worked outside the home. ((See Lynn Dumenil,The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 113.)) It was a decade in which new technologies decreased time requirements for household chores, and one in which standards of cleanliness and order in the home rose to often impossible standards. It was a decade in which women would, finally, have the opportunity to fully exercise their right to vote, and one in which the often thinly-bound women’s coalitions that had won that victory splintered into various causes. Finally, it was a decade in which images such as the “flapper” would give women new modes of representing femininity, and one in which such representations were often inaccessible to women of certain races, ages, and socio-economic classes.

Women undoubtedly gained much in the 1920s. There was a profound and keenly felt cultural shift which, for many women, meant increased opportunity to work outside the home. The number of professional women, for example, significantly rose in the decade. But limits still existed, even for professional women. Occupations such as law and medicine remained overwhelmingly “male”: the majority of women professionals were in “feminized” professions such as teaching and nursing. And even within these fields, it was difficult for women to rise to leadership positions.

Further, it is crucial not to over-generalize the experience of all women based on the experiences of a much-commented upon subset of the population. A woman’s race, class, ethnicity, and marital status all had an impact on both the likelihood that she worked outside the home, as well as the types of opportunities that were available to her. While there were exceptions, for many minority women, work outside the home was not a cultural statement but rather a financial necessity (or both), and physically demanding, low-paying domestic service work continued to be the most common job type. Young, working class white women were joining the workforce more frequently, too, but often in order to help support their struggling mothers and fathers.

For young, middle-class, white women—those most likely to fit the image of the carefree flapper—the most common workplace was the office. These predominantly single women increasingly became clerks, jobs that had been primarily “male” earlier in the century. But here, too, there was a clear ceiling. While entry-level clerk jobs became increasingly feminized, jobs at a higher, more lucrative level remained dominated by men. Further, rather than changing the culture of the workplace, the entrance of women into the lower-level jobs primarily changed the coding of the jobs themselves. Such positions simply became “women’s work.”

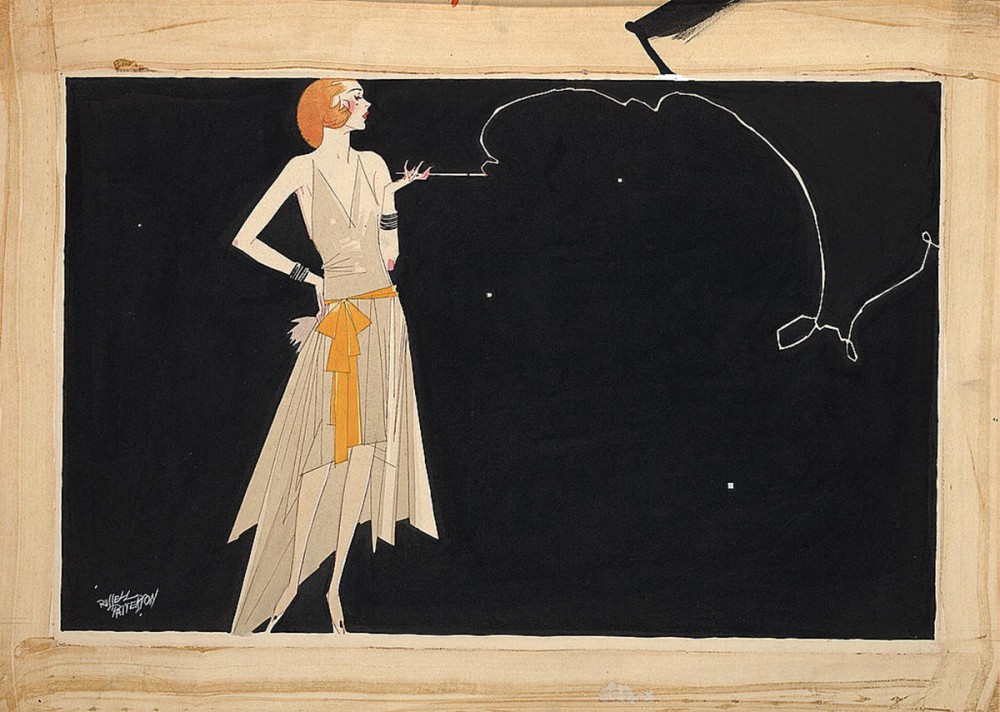

The frivolity, decadence, and obliviousness of the 1920s was embodied in the image of the flapper, the stereotyped carefree and indulgent woman of the Roaring Twenties depicted by Russell Patterson’s drawing. Russell Patterson, artist, “Where there’s smoke there’s fire,” c. 1920s. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2009616115/.

Finally, as these same women grew older and married, social changes became even subtler. Married women were, for the most part, expected to remain in the domestic sphere. And while new patterns of consumption gave them more power and, arguably, more autonomy, new household technologies and philosophies of marriage and child-rearing increased expectations, further tying these women to the home—a paradox that becomes clear in advertisements such as the one in the Chicago Tribune. Of course, the number of women in the workplace cannot exclusively measure changes in sex and gender norms. Attitudes towards sex, for example, continued to change in the 1920s, as well, a process that had begun decades before. This, too, had significantly different impacts on different social groups. But for many women—particularly young, college-educated white women—an attempt to rebel against what they saw as a repressive “Victorian” notion of sexuality led to an increase in premarital sexual activity strong enough that it became, in the words of one historian, “almost a matter of conformity.” ((Nancy Cott, The Grounding of Modern Feminism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 150.))

In the homosexual community, meanwhile, a vibrant gay culture grew, especially in urban centers such as New York. While gay males had to contend with increased policing of the gay lifestyle (especially later in the decade), in general they lived more openly in New York in the 1920s than they would be able to for many decades following World War II. ((George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994).)) At the same time, for many lesbians in the decade, the increased sexualization of women brought new scrutiny to same-sex female relationships previously dismissed as harmless. ((Cott, Grounding, 160.))

Ultimately, the most enduring symbol of the changing notions of gender in the 1920s remains the flapper. And indeed, that image was a “new” available representation of womanhood in the 1920s. But it is just that: a representation of womanhood of the 1920s. There were many women in the decade of differing races, classes, ethnicities, and experiences, just as there were many men with different experiences. For some women, the 1920s were a time of reorganization, new representations and new opportunities. For others, it was a decade of confusion, contradiction, new pressures and struggles new and old.

VI. “The New Negro”

Just as cultural limits loosened across the nation, the 1920s represented a period of serious self-reflection among African Americans, most especially those in northern ghettos. New York City was a popular destination of American blacks during the Great Migration. The city’s black population grew 257%, from 91,709 in 1910 to 327,706 by 1930 (the white population grew only 20%). ((Mark R. Schneider, “We Return Fighting”: The Civil Rights Movement in the Jazz Age. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002), 21.)) Moreover, by 1930, some 98,620 foreign-born blacks had migrated to the U.S. Nearly half made their home in Manhattan’s Harlem district. ((Philip Kasinitz, Caribbean New York: Black Immigrants and the Politics of Race (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992), 25.))

Harlem originally lay between Fifth Avenue to Eighth Avenue and 130th Street to 145th Street. By 1930, the district had expanded to 155th Street and was home to 164,000 mostly African Americans. Continuous relocation to “the greatest Negro City in the world” exacerbated problems with crime, health, housing, and unemployment. ((The New Negro of the Harlem Renaissance (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997/1925), 301.)) Nevertheless, it importantly brought together a mass of black people energized by the population’s World War I military service, the urban environment, and for many, ideas of Pan-Africanism or Garveyism. Out of the area’s cultural ferment emerged the Harlem Renaissance, or what was then termed “New Negro Movement.” While this stirring in self-consciousness and racial pride was not confined to Harlem, this district was truly as James Weldon Johnson described: “The Culture Capital.” ((Ibid.)) The Harlem Renaissance became a key component in African Americans’ long history of cultural and intellectual achievements.

Alain Locke did not coin “New Negro”, but he did much to popularize it. In the 1925 The New Negro, Locke proclaimed that the generation of subservience was no more—“we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation.” Bringing together writings by men and women, young and old, black and white, Locke produced an anthology that was of African Americans, rather than only about them. The book joined many others. Popular Harlem Renaissance writers published some twenty-six novels, ten volumes of poetry, and countless short stories between 1922 and 1935. ((Joan Marter, editor, The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Volume 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 448.)) Alongside the well-known Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, women writers like Jessie Redmon Fauset and Zora Neale Hurston published nearly one-third of these novels. While themes varied, the literature frequently explored and countered pervading stereotypes and forms of American racial prejudice.

The Harlem Renaissance was manifested in theatre, art, and music. For the first time, Broadway presented black actors in serious roles. The 1924 production, Dixie to Broadway, was the first all-black show with mainstream showings. ((James F. Wilson, Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race, and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 116.)) In art, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Aaron Douglas, and Palmer Hayden showcased black cultural heritage as well as captured the population’s current experience. In music, jazz rocketed in popularity. Eager to hear “real jazz,” whites journeyed to Harlem’s Cotton Club and Smalls. Next to Greenwich Village, Harlem’s nightclubs and speakeasies (venues where alcohol was publicly consumed) presented a place where sexual freedom and gay life thrived. Unfortunately, while headliners like Duke Ellington were hired to entertain at Harlem’s venues, the surrounding black community was usually excluded. Furthermore, black performers were often restricted from restroom use and relegated to service door entry. As the Renaissance faded to a close, several Harlem Renaissance artists went on to produce important works indicating that this movement was but one component in African American’s long history of cultural and intellectual achievements. ((Cary D, Wintz, and Paul Finkelman, Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance,>Volume 2 (New York: Routledge, 2004), 910-11.))

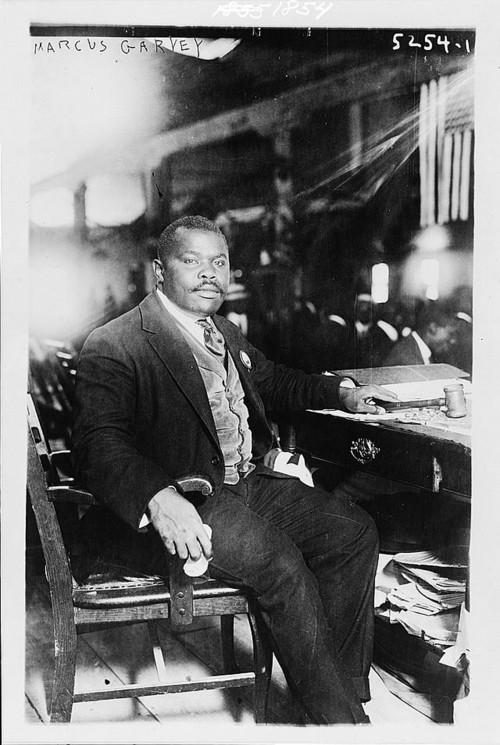

Garveyism, criticized as too radical, nevertheless formed a substantial following, and was a major stimulus for later black nationalistic movements. Photograph of Marcus Garvey, August 5, 1924. Library of Congress.

The explosion of African American self-expression found multiple outlets in politics. In the 1910s and 20s, perhaps no one so attracted disaffected black activists as Marcus Garvey. Garvey was a Jamaican publisher and labor organizer who arrived in New York City in 1916. Within just a few years of his arrival, he built the largest black nationalist organization in the world, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). ((For Garvey, see Colin Grant, Negro with a Hat: The Rise and Fall of Marcus Garvey (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Judith Stein, The World of Marcus Garvey: Race and Class in Modern Society (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986); Ula Yvette Taylor, The Veiled Garvey: The Life and Times of Amy Jacques Garvey (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).)) Inspired by Pan-Africanism and Booker T. Washington’s model of industrial education, and critical of what he saw as DuBois’s elitist strategies in service of black elites, Garvey sought to promote racial pride, encourage black economic independence, and root out racial oppression in Africa and the Diaspora. ((Winston James, Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth-Century America (London: Verso, 1998).))

Headquartered in Harlem, the UNIA published a newspaper, Negro World, and organized elaborate parades in which members, “Garveyites,” dressed in ornate, militaristic regalia and marched down city streets. The organization criticized the slow pace of the judicial focus of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as this organization’s acceptance of memberships and funds from whites. “For the Negro to depend on the ballot and his industrial progress alone,” Garvey opined, “will be hopeless as it does not help him when he is lynched, burned, jim-crowed, and segregated.” In 1919, the UNIA announced plans to develop a shipping company called the Black Star Line as part of a plan that pushed for blacks to reject the political system and to “return to Africa” instead.” Most of the investments came in the form of shares purchased by UNIA members, many of whom heard Garvey give rousing speeches across the country about the importance of establishing commercial ventures between African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and Africans. ((Grant; Stein; Taylor.))

Garvey’s detractors disparaged these public displays and poorly managed business ventures, and they criticized Garvey for peddling empty gestures in place of measures that addressed the material concerns of African Americans. NAACP leaders depicted Garvey’s plan as one that simply said, “Give up! Surrender! The struggle is useless.” Enflamed by his aggressive attacks on other black activists and his radical ideas of racial independence, many African American and Afro-Caribbean leaders worked with government officials and launched the “Garvey Must Go” campaign, which culminated in his 1922 indictment and 1925 imprisonment and subsequent deportation for “using the mails for fraudulent purposes.” The UNIA never recovered its popularity or financial support, even after Garvey’s pardon in 1927, but his movement made a lasting impact on black consciousness in the United States and abroad. He inspired the likes of Malcolm X, whose parents were Garveyites, and Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana. Garvey’s message, perhaps best captured by his rallying cry, “Up, you mighty race,” resonated with African Americans who found in Garveyism a dignity not granted them in their everyday lives. In that sense, it was all too typical of the Harlem Renaissance. ((Ibid.))

VII. Culture War

For all of its cultural ferment, however, the 1920s were also a difficult time for radicals and immigrants and anything “modern.” Fear of foreign radicals led to the executions of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian anarchists, in 1927. In May 1920, the two had been arrested for robbery and murder connected with an incident at a Massachusetts factory. Their guilty verdicts were appealed for years as the evidence surrounding their convictions was slim. For instance, while one eyewitness claimed that Vanzetti drove the get-away car, but accounts of others described a different person altogether. Nevertheless, despite around world lobbying by radicals and a respectable movement among middle class Italian organizations in the U.S., the two men were executed on August 23, 1927. Vanzetti conceivably provided the most succinct reason for his death, saying, “This is what I say . . . . I am suffering because I am a radical and indeed I am a radical; I have suffered because I was an Italian, and indeed I am an Italian.” ((Nicola Sacco, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti (New York: Octagon Books, 1971 [1928]), 272.))

Many Americans expressed anxieties about the changes that had remade the United States and, seeking scapegoats, many middle-class white Americans pointed to Eastern European and Latin American immigrants (Asian immigration had already been almost completely prohibited), or African Americans who now pushed harder for civil rights and after migrating out of the American South to northern cities as a part of the Great Migration, that mass exodus which carried nearly half a million blacks out of the South between just 1910-1920. Protestants, meanwhile, continued to denounce the Roman Catholic Church and charged that American Catholics gave their allegiance to the Pope and not to their country.

In 1921, Congress passed the Emergency Immigration Act as a stopgap immigration measure, and then, three years later, permanently established country-of-origin quotas through the National Origins Act. The number of immigrants annually admitted to the United States from each nation was restricted to two percent of the population who had come from that country and resided in the United States in 1890. (By pushing back three decades, past the recent waves of “new” immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Asia, the law made it extremely difficult for immigrants outside of Northern Europe to legally enter the United States.) The act also explicitly excluded all Asians, though, to satisfy southern and western growers, temporarily omitted restrictions on Mexican immigrants. The Sacco and Vanzetti trial and sweeping immigration restrictions pointed to a rampant nativism. A great number of Americans worried about a burgeoning America that did not resemble the one of times past. Many wrote of an American riven by a cultural war.

VIII. Fundamentalist Christianity

In addition to alarms over immigration and the growing presence of Catholicism and Judaism, a new core of Christian fundamentalists were very much concerned about relaxed sexual mores and increased social freedoms, especially as found in city centers. Although never a centralized group, most fundamentalists lashed out against what they saw as a sagging public morality, a world in which Protestantism seemed challenged by Catholicism, women exercised ever greater sexual freedoms, public amusements encouraged selfish and empty pleasures, and critics mocked prohibition through bootlegging and speakeasies.

Christian Fundamentalism arose most directly from a doctrinal dispute among Protestant leaders. Liberal theologians sought to intertwine religion with science and secular culture. These “Modernists,” influenced by the Biblical scholarship of nineteenth century German academics, argued that Christian doctrines about the miraculous might be best understood metaphorically. The church, they said, needed to adapt itself to the world. According to the Baptist pastor Harry Emerson Fosdick, the “coming of Christ” might occur “slowly…but surely, [as] His will and principles [are] worked out by God’s grace in human life and institutions.” ((Harry Emerson Fosdick, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” Christian Work 102 (June 10, 1922): 716–722.)) The social gospel, which encouraged Christians to build the Kingdom of God on earth by working against social and economic inequality, was very much tied to liberal theology.

During the 1910s, funding from oil barons Lyman and Milton Stewart enabled the evangelist A. C. Dixon to commission some ninety essays to combat religious liberalism. The collection, known as The Fundamentals, became the foundational documents of Christian fundamentalism, from which the movement’s name is drawn. Contributors agreed that Christian faith rested upon literal truths, that Jesus, for instance, would physically return to earth at the end of time to redeem the righteous and damn the wicked. Some of the essays put forth that human endeavor would not build the Kingdom of God, while others covered such subjects as the virgin birth and biblical inerrancy. American Fundamentalists spanned Protestant denominations and borrowed from diverse philosophies and theologies, most notably the holiness movement, the larger revivalism of the nineteenth century and new dispensationalist theology (in which history proceeded, and would end, through “dispensations” by God). They did, however, all agree that modernism was the enemy and the Bible was the inerrant word of God. It was a fluid movement often without clear boundaries, but it featured many prominent clergymen, including the well-established and extremely vocal John Roach Straton (New York), J. Frank Norris (Texas), and William Bell Riley (Minnesota). ((George Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980).))

On March 21, 1925 in a tiny courtroom in Dayton, Tennessee, Fundamentalists gathered to tackle the issues of creation and evolution. A young biology teacher, John T. Scopes, was being tried for teaching his students evolutionary theory in violation of the Butler Act, a state law preventing evolutionary theory or any theory that denied “the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible” from being taught in publically-funded Tennessee classrooms. Seeing the act as a threat to personal liberty, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) immediately sought a volunteer for a “test” case, hoping that the conviction and subsequent appeals would lead to a day in the Supreme Court, testing the constitutionality of the law. It was then that Scopes, a part-time teacher and coach, stepped up and voluntarily admitted to teaching evolution (Scopes’ violation of the law was never in question). Thus the stage was set for the pivotal courtroom showdown—“the trial of the century”—between the champions and opponents of evolution that marked a key moment in an enduring American “culture war.” ((Edward J. Larson, Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate over Science and Religion (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997).))

The case became a public spectacle. Clarence Darrow, an agnostic attorney and a keen liberal mind from Chicago, volunteered to aid the defense came up against William Jennings Bryan. Bryan, the “Great Commoner,” was the three-time presidential candidate who in his younger days had led the political crusade against corporate greed. He had done so then with a firm belief in the righteousness of his cause, and now he defended biblical literalism in similar terms. The theory of evolution, Bryan said, with its emphasis on the survival of the fittest, “would eliminate love and carry man back to a struggle of tooth and claw.” ((Leslie H. Allen, editor, Bryan and Darrow at Dayton: The Record and Documents of the “Bible-Evolution” Trial (New York: Arthur Lee, 1925).))

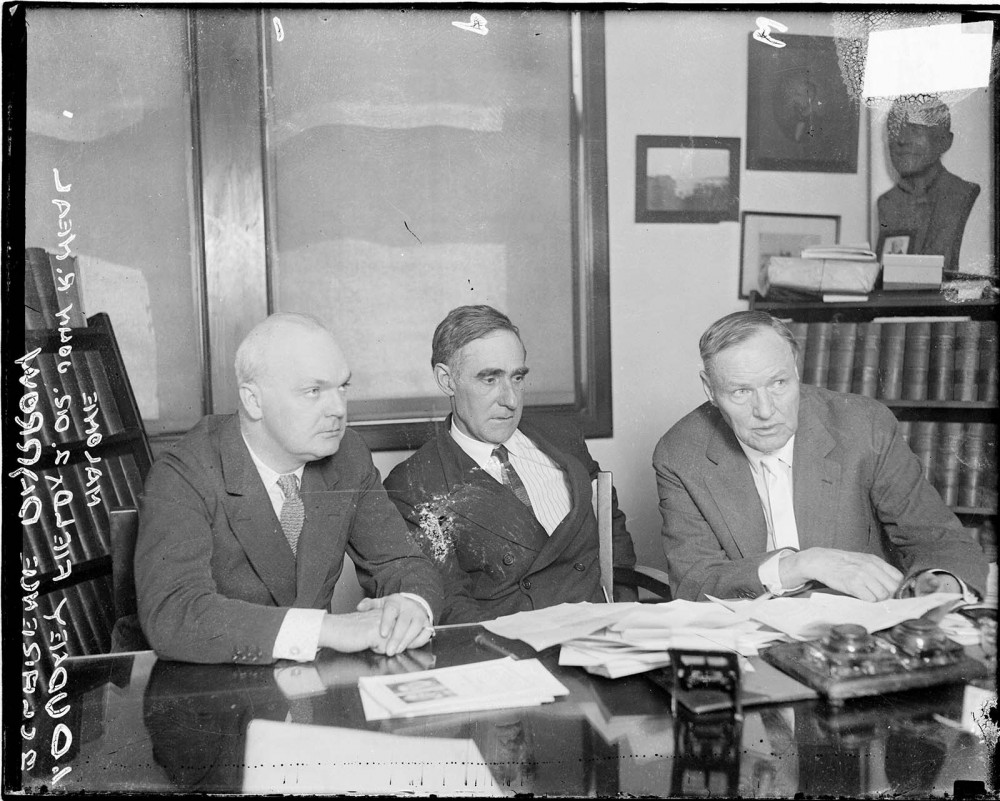

During the Scopes Trial, Clarence Darrow (right) savaged the idea of a literal interpretation of the Bible. “Dudley Field Malone, Dr. John R. Neal, and Clarence Darrow in Chicago, Illinois.” The Clarence Darrow Digital Collection.

Newspapermen and spectators flooded the small town of Dayton. Across the nation, Americans tuned their radios to the national broadcasts of a trial that dealt with questions of religious liberty, academic freedom, parental rights, and the moral responsibility of education. For six days in July, the men and women of America were captivated as Bryan presented his argument on the morally corrupting influence of evolutionary theory (and pointed out that Darrow made a similar argument about the corruptive potential of education during his defense of the famed killers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb a year before). Darrow eloquently fought for academic freedom. ((Larson.))

At the request of the defense, Bryan took the stand as an “expert witness” on the Bible. At his age, he was no match for Darrow’s famous skills as a trial lawyer and his answers came across as blundering and incoherent, particularly as he was not in fact a literal believer in all of the Genesis account (believing—as many anti-evolutionists did—that the meaning of the word “day” in the book of Genesis could be taken as allegory) and only hesitantly admitted as much, not wishing to alienate his fundamentalist followers. Additionally, Darrow posed a series of unanswerable questions: Was the “great fish” that swallowed the prophet Jonah created for that specific purpose? What precisely happened astronomically when God made the sun stand still? Bryan, of course, could cite only his faith in miracles. Tied into logical contradictions, Bryan’s testimony was a public relations disaster, although his statements were expunged from the record the next day and no further experts were allowed—Scopes’ guilt being established, the jury delivered a guilty verdict in minutes. The case was later thrown out on technicality. But few cared about the verdict. Darrow had, in many ways, at least to his defenders, already won: the fundamentalists seemed to have taken a beating in the national limelight. Journalist and satirist H. L. Mencken characterized the “circus in Tennessee” as an embarrassment for fundamentalism, and modernists remembered the “Monkey Trial” as a smashing victory. If fundamentalists retreated from the public sphere, they did not disappear entirely. Instead, they went local, built a vibrant subculture, and emerged many decades later stronger than ever. ((Ibid.))

IX. Rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK)

Suspicions of immigrants, Catholics, and modernists contributed to a string of reactionary organizations. None so captured the imaginations of the country as the reborn Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a white supremacist organization that expanded beyond its Reconstruction Era anti-black politics to now claim to protect American values and way of life from blacks, feminists (and other radicals), immigrants, Catholics, Jews, atheists, bootleggers, and a host of other imagined moral enemies.

Two events in 1915 are widely credited with inspiring the rebirth of the Klan: the lynching of Leo Frank and the release of The Birth of the Nation, a popular and groundbreaking film that valorized the Reconstruction Era Klan as a protector of feminine virtue and white racial purity. Taking advantage of this sudden surge of popularity, Colonel William Joseph Simmons organized what is often called the “second” Ku Klux Klan in Georgia in late 1915. This new Klan, modeled after other fraternal organizations with elaborate rituals and a hierarchy, remained largely confined to Georgia and Alabama until 1920, when Simmons began a professional recruiting effort that resulted in individual chapters being formed across the country and membership rising to an estimated five million. ((Nancy MacLean, Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan (New York: Oxford University Press. 1994).))

Partly in response to the migration of Southern blacks to Northern cities during World War I, the KKK expanded above the Mason-Dixon. Membership soared in Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, and Portland, while Klan-endorsed mayoral candidates won in Indianapolis, Denver, and Atlanta. (( Kenneth T. Jackson, The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967).)) The Klan often recruited through fraternal organizations such as the Freemasons and through various Protestant churches. In many areas, local Klansmen would visit churches of which they approved and bestow a gift of money upon the presiding minister, often during services. The Klan also enticed people to join through large picnics, parades, rallies, and ceremonies. The Klan established a women’s auxiliary in 1923 headquartered in Little Rock, Arkansas. The Women of the Ku Klux Klan mirrored the KKK in practice and ideology and soon had chapters in all forty-eight states, often attracting women who were already part of the prohibition movement, the defense of which was a centerpiece of Klan activism. ((MacLean.))

Contrary to its perception of as a primarily Southern and lower-class phenomenon, the second Klan had a national reach composed largely of middle-class people. Sociologist Rory McVeigh surveyed the KKK newspaper Imperial Night-Hawk for the years 1923 and 1924, at the organization’s peak, and found the largest number of Klan-related activities to have occurred in Texas, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Illinois, and Georgia. The Klan was even present in Canada, where it was a powerful force within Saskatchewan’s Conservative Party. In many states and localities, the Klan dominated politics to such a level that one could not be elected without the support of the KKK. For example, in 1924, the Klan supported William Lee Cazort for governor of Arkansas, leading his opponent in the Democratic Party primary, Thomas Terral, to seek honorary membership through a Louisiana klavern so as not to be tagged as the anti-Klan candidate. In 1922, Texans elected Earle B. Mayfield, an avowed Klansman who ran openly as that year’s “klandidate,” to the United States Senate. At its peak the Klan claimed between four and five million members. ((George Brown Tindall, The Emergence of the New South: 1913-1945 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967).))

Despite the breadth of its political activism, the Klan is today remembered largely as a violent vigilante group—and not without reason. Members of the Klan and affiliated organizations often carried out acts of lynching and “nightriding”—the physical harassment of bootleggers, union activists, civil rights workers, or any others deemed “immoral” (such as suspected adulterers) under the cover of darkness or while wearing their hoods and robes. In fact, Klan violence was extensive enough in Oklahoma that Governor John C. Walton placed the entire state under martial law in 1923. Witnesses testifying before the military court disclosed accounts of Klan violence ranging from the flogging of clandestine brewers to the disfiguring of a prominent black Tulsan for registering African Americans to vote. In Houston, Texas, the Klan maintained an extensive system of surveillance that included tapping telephone lines and putting spies into the local post office in order to root out “undesirables.” A mob that organized and led by Klan members in Aiken, South Carolina, lynched Bertha Lowman and her two brothers in 1926, but no one was ever prosecuted: the sheriff, deputies, city attorney, and state representative all belonged to the Klan. ((MacLean; Wyn Craig Wade, The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America (New York, Oxford University Press, 1998).))

The Klan dwindled in the face of scandal and diminished energy over the last years of the 1920s. By 1930, the Klan only had about 30,000 members and it was largely spent as a national force, only to appear again as a much diminished force during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 60s.

X. Conclusion

In his inauguration speech in 1929, Herbert Hoover told Americans that the Republican Party had brought prosperity. Even ignoring stubbornly large rates of poverty and unparalleled levels of inequality, he could not see the weaknesses behind the decade’s economy. Even as the new culture of consumption promoted new freedoms, it also promoted new insecurities. An economy built on credit exposed the nation to tremendous risk. Flailing European economies, high tariffs, wealth inequality, a construction bubble, and an ever-more flooded consumer market loomed dangerously until the Roaring Twenties would grind to a halt. In a moment the nation’s glitz and glamour seemed to give way to decay and despair. For farmers, racial minorities, unionized workers, and other populations that did not share in 1920s prosperity, the veneer of a Jazz Age and a booming economy had always been a fiction. But for them, as for millions of Americans, end of an era was close. The Great Depression loomed.

Contributors

This chapter was edited by Brandy Thomas Wells, with content contributions by Micah Childress, Mari Crabtree, Maggie Flamingo, Guy Lancaster, Emily Remus, Colin Reynolds, Kristopher Shields, and Brandy Thomas Wells.

Recommended Reading

- Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Douglas, Ann. Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1995.

- The Culture of Consumption: Critical Essays in American History, 1880- 1980. Edited by Fox, Richard Wightman, and Lears, T. J. Jackson. New York: Pantheon, 1983.

- Grant, Colin. Negro with a Hat: The Rise and Fall of Marcus Garvey. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Huggins, Nathan. Harlem Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Larson, Edward. Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate over Science and Religion. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- MacLean, Nancy. Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Marsden, George M. Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth- Century Evangelicalism: 1870-1925. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Montgomery, David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865-1925. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Ngai, Mae M., Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2010.

- Sanchez, George. Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Tindall, George Brown. The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967.

- Wilkerson, Isabel. The Warmth of Other Sons: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. New York: Vintage, 2010.