*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

Speaking to Detroit autoworkers in October of 1980, Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan described what he saw as the American Dream under Democratic President Jimmy Carter. The family garage may have still held two cars, cracked Reagan, but they were “both Japanese and they’re out of gas.” ((Ronald Reagan quoted in Steve Neal, “Reagan Assails Carter On Auto layoffs,” Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1980, 5.)) The charismatic former governor of California suggested that a once-proud nation was running on empty, economically and politically outpaced by foreign competitors. But Reagan held out hope for redemption. Stressing the theme of “national decline,” he nevertheless promised to make the United States once again a glorious “city upon a hill.” ((Ronald Reagan quoted in James T. Patterson, Restless Giant: The United States From Watergate to Bush v. Gore (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 152.)) In November, Reagan’s vision of a dark present and a bright future triumphed.

Reagan rode the wave of a powerful political movement often referred to as the “New Right,” in contrast to the more moderate brand of conservatism prevalent after World War II. By the 1980s the New Right had evolved into the most influential wing of the Republican Party and could claim significant credit for its electoral success. The conservative ascendency built upon the gradual unraveling of the New Deal political order during the 1960s and 1970s. ((See Chapter 28, “The Unraveling.” )) It enjoyed the guidance of skilled politicians like Reagan but drew tremendous energy from a broad range of grassroots activists. Countless ordinary citizens–newly mobilized Christian conservatives, in particular–helped the Republican Party steer the country onto a rightward course. The New Right also attracted support from “Reagan Democrats,” blue-collar voters who had lost faith in the old liberal creed, All the while, enduring conflicts over race, economic policy, gender and sexual politics, and foreign affairs fatally fractured the liberal consensus that had dominated American politics since the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt.

The rise of the right affected Americans’ everyday lives in numerous ways. The Reagan administration embraced “free market” economic theory, dispensing with the principles of income redistribution and social welfare spending that had animated the New Deal and Great Society. Conservative policymakers tilted the regulatory and legal landscape of the United States toward corporations and wealthy individuals. This project depended foremost on weakening the “rights” framework that had undergirded advancements by African Americans, Latinos and Latinas, women, lesbians and gays, and other marginalized groups.

In many ways, however, the rise of the right promised more than it delivered. Battered but intact, the social welfare programs of the New Deal and Great Society (Social Security, Medicaid, Aid to Families With Dependent Children) survived the 1980s. Despite Republican vows of fiscal discipline, both the federal government and the national debt ballooned. At the end of the decade, conservative Christians viewed popular culture as more vulgar and hostile to their values than ever before. In the near term, the New Right registered only partial victories on a range of public policies and cultural issues. Yet, from a long-term perspective conservatives achieved a subtler and more enduring transformation of American politics and society. In the words of one historian, the conservative movement successfully “changed the terms of debate and placed its opponents on the defensive.” ((Robert Self, All in the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy Since the 1960s (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012), 369. )) Liberals and their programs and their policies did not disappear, but they increasingly fought battles on terrain chosen by the New Right.

II. Conservative Ascendance

The “Reagan Revolution” marked the culmination of a long process of political mobilization on the American right. In the first two decades after World War II the New Deal seemed firmly embedded in American electoral politics and public policy. Even two-term Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower declined to roll back the welfare state. To be sure, William F. Buckley tapped into a deep vein of elite conservatism in 1955 by announcing in the first issue of National Review that his magazine “stands athwart history yelling Stop.” ((William F. Buckley, Jr., “Our Mission Statement,” National Review, November 19, 1955. http://www.nationalreview.com/article/223549/our-mission-statement-william-f-buckley-jr. Accessed on June 29, 2015. )) Senator Joseph McCarthy and John Birch Society founder Robert Welch stirred anti-communist fervor. But in general, the far right lacked organizational cohesion. Following Lyndon Johnson’s resounding defeat of Republican standard-bearer Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election, many observers declared American conservatism finished. New York Times columnist James Reston wrote that Goldwater had “wrecked his party for a long time to come.” ((James Reston, “What Goldwater Lost: Voters Rejected His Candidacy, Conservative Cause and the G.O.P.,” New York Times, November 4, 1964, 23. ))

The Conservative insurgency occurred within both major political parties, but the New Right gradually coalesced under the Republican tent. The heightened appeal of conservatism had several causes. The expansive social and economic agenda of Johnson’s Great Society reminded anti-communists of Soviet-style central planning and enflamed fiscal conservatives worried about deficits. Race also drove the creation of the New Right. The civil rights movement, along with the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, upended the racial hierarchy of the Jim Crow South. All of these occurred under Democratic leadership, pushing the South toward the Republican Party. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Black Power, affirmative action, and court-ordered busing of children between schools to achieve racial balance brought “white backlash” to the North, often in cities previously known for political liberalism. To many ordinary white Americans, the urban rebellions, antiwar protests, and student uprisings of the late 1960s unleashed social chaos. At the same time, declining wages, rising prices, and growing tax burdens brought economic vulnerability to many working- and middle-class citizens who long formed the core of the New Deal coalition. Liberalism no longer seemed to offer the great mass of white Americans a roadmap to prosperity, so they searched for new political solutions.

Former Alabama governor and conservative Democrat George Wallace masterfully exploited the racial, cultural, and economic resentments of working-class whites during his presidential runs in 1968 and 1972. Wallace’s record as a staunch segregationist made him a hero in the Deep South, where he won five states as a third-party candidate in the 1968 general election. Wallace’s populist message also resonated with blue-collar voters in the industrial North who felt left behind by the rights revolution. On the campaign stump, the fiery candidate lambasted hippies, anti-war protestors, and government bureaucrats. He assailed female welfare recipients for “breeding children as a cash crop” and ridiculed “over-educated, ivory-tower” intellectuals who “don’t know how to park a bicycle straight.” ((George Wallace quoted in William Chafe, The Unfinished Journey: America Since World War II (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 377. )) Yet, Wallace also advanced progressive proposals for federal job training programs, a minimum wage hike, and legal protections for collective bargaining. Running as a Democrat in 1972 (and with anti-busing rhetoric as a new arrow in his quiver), Wallace captured the Michigan primary and polled second in the industrial heartland of Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Indiana. In May 1972 an assassin’s bullet left Wallace paralyzed and ended his campaign. Nevertheless, his amalgamation of older, New Deal-style proposals and conservative populism emblemized the rapid re-ordering of party loyalties in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Richard Nixon similarly harnessed the new right’s sense of grievance through his rhetoric about “law and order” and the “silent majority.” ((James Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 735-736. )) But Nixon and his Republican successor, Gerald Ford, continued to accommodate the politics of the New Deal order. The new right remained restive.

Christian conservatives also felt themselves under siege from liberalism. In the early 1960s, the Supreme Court decisions prohibiting teacher-led prayer (Engel v. Vitale) and Bible reading in public schools (Abington v. Schempp) led some on the right to conclude that a liberal judicial system threatened Christian values. In the following years, the counterculture’s celebration sex and drugs, along with relaxed obscenity and pornography laws, intensified the conviction that “permissive” liberalism encouraged immorality in private life. Evangelical Protestants—Christians who professed a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, upheld the Bible as an infallible source of truth, and felt a duty to convert, or evangelize, nonbelievers—comprised the core of the so-called “religious right.” The movement also drew energy from devout Catholics. The development of the religious right was not inevitable for several reasons. First, many evangelicals had for decades eschewed politics in favor of spiritual matters; moreover, evangelicalism did not necessarily lead to conservative politics (Democrat Jimmy Carter was an evangelical). Second, working-class Roman Catholics had a long record of loyalty to the Democratic Party. Third, the alliance between evangelicals and Catholics had to overcome decades of mutual antagonism. Only the common enemy of liberalism brought the groups together.

With increasing assertiveness in the 1960s and 1970s, Christian conservatives mobilized to protect the “traditional” family. Women comprised a striking number of the religious right’s foot soldiers. In 1968 and 1969 a group of newly politicized mothers in Anaheim, California led a sustained protest against sex education in public schools. The successful campaign of these “suburban warriors” reflected a widespread belief among Christian conservatives that permissive liberal morality, often emanating from public institutions, threatened their children. ((Lisa McGirr, Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right ( Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 227-231. )) A number of other issues also stirred conservative women. Catholic activist Phyllis Schlafly marshaled opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment, while evangelical pop singer Anita Bryant drew national headlines for her successful fight to repeal Miami’s gay rights ordinance in 1977. In 1979, Beverly LaHaye (whose husband Tim–an evangelical pastor in San Diego–would later co-author the wildly popular Left Behind Christian book series) founded Concerned Women for America, which linked small groups of local activists opposed to the ERA, abortion, homosexuality, and no-fault divorce.

Activists like Schlafly and LaHaye valorized motherhood as the highest calling of all women. Abortion therefore struck at the core of their female identity. More than perhaps any other issue, abortion drew different segments of the religious right—Catholics and Protestants, women and men—together. The Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling outraged many devout Catholics, including Long Island housewife and political novice Ellen McCormack. In 1976, McCormack entered the Democratic presidential primaries in an unsuccessful attempt to steer the party to a pro-life position. Roe v. Wade also intensified anti-abortion sentiment among many evangelicals (who had been less universally opposed to the procedure than their Catholic counterparts). Christian author Francis Schaeffer cultivated evangelical opposition to abortion through the 1979 documentary film Whatever Happened to the Human Race? arguing that the “fate of the unborn is the fate of the human race.” ((Francis Schaeffer quoted in Whatever Happened to the Human Race? (Episode I), Film, directed by Franky Schaeffer, (1979, USA, Franky Schaeffer V Productions). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQAyIwi5l6E. Accessed June 30, 2015. )) With the procedure framed in stark, existential terms, many evangelicals felt compelled to combat the procedure through political action.

This book cover succinctly demonstrates the mindset of many conservatives in the Reagan era: what happened to the human race? http://users.aber.ac.uk/jrl/scan0001.jpg.

Grassroots passion drove anti-abortion activism, but a set of religious and secular institutions turned the various strands of the New Right into a sophisticated movement. In 1979 Jerry Falwell—a Baptist minister and religious broadcaster from Lynchburg, Virginia—founded the Moral Majority, an explicitly political organization dedicated to advancing a “pro-life, pro-family, pro-morality, and pro-American” agenda. The Moral Majority skillfully weaved together social and economic appeals to make itself a force in Republican politics. Secular, business-oriented institutions also joined the attack on liberalism, fueled by stagflation and by the federal government’s creation of new regulatory agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Conservative business leaders bankrolled new “think tanks” like the Heritage Foundation and the Cato Institute. These organizations provided grassroots activists with ready-made policy prescriptions. Other business leaders took a more direct approach by hiring Washington lobbyists and creating Political Action Committees (PACs) to press their agendas in the halls of Congress and federal agencies. Between 1976 and 1980 the number of corporate PACS rose from under 300 to over 1200.

Grassroots activists and business leaders received unlikely support from a circle of “neoconservatives”—disillusioned intellectuals who had rejected liberalism and the Left and become Republicans. Irving Kristol, a former Marxist who went on to champion free-market capitalism as a Wall Street Journal columnist, defined a neoconservative as a “liberal who has been mugged by reality.” ((Walter Goodman, “Irving Kristol: Patron Saint of the New Right,” New York Times Magazine, December 6, 1981. http://www.nytimes.com/1981/12/06/magazine/irving-kristol-patron-saint-of-the-new-right.html. Accessed June 24, 2015. )) Neoconservative journals like Commentary and Public Interest argued that the Great Society had proven counterproductive, perpetuating the poverty and racial segregation that it aimed to cure. By the middle of the 1970s, neoconservatives felt mugged by foreign affairs as well. As ardent Cold Warriors, they argued that Nixon’s policy of détente left the United States vulnerable to the Soviet Union.

In sum, several streams of conservative political mobilization converged in the late 1970s. Each wing of the burgeoning New Right—disaffected Northern blue-collar workers, white Southerners, evangelicals and devout Catholics, business leaders, disillusioned intellectuals, and Cold War hawks—turned to the Republican Party as the most effective vehicle for their political counter-assault on liberalism and the New Deal political order. After years of mobilization, the domestic and foreign policy catastrophes of the Carter administration provided the head winds that brought the conservative movement to shore.

III. The Conservatism of the Carter Years

The election of Jimmy Carter in 1976 brought a Democrat to the White House for the first time since 1969. Large Democratic majorities in Congress provided the new president with an opportunity to move aggressively on the legislative front. With the infighting of the early 1970s behind them, many Democrats hoped the Carter administration would update and expand the New Deal. But Carter won the presidency on a wave of post-Watergate disillusionment with government that did not translate into support for liberal ideas. Events outside Carter’s control certainly helped discredit liberalism, but the president’s own policies also pushed national politics further to the right. In his 1978 State of the Union address, Carter lectured Americans that “[g]overnment cannot solve our problems…it cannot eliminate poverty, or provide a bountiful economy, or reduce inflation, or save our cities, or cure illiteracy, or provide energy.” ((Jimmy Carter, 1978 State of the Union Address, Jan. 19, 1878, Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum, http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/documents/speeches/su78jec.phtml, accessed June 24, 2015.)) The statement neatly captured the ideological transformation of the county. Rather than leading a resurgence of American liberalism, Carter became, as one historian put it, “the first president to govern in a post-New Deal framework.” ((Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: The New Press, 2010),12.))

In its early days the Carter administration embraced several policies backed by liberals. It pushed an economic stimulus package containing $4 billion in public works, extended food stamp benefits to 2.5 million new recipients, enlarged the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income households, and expanded the Nixon-era Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA). ((Patterson, Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 113. )) But the White House quickly realized that Democratic control of Congress did not guarantee support for its initially left-leaning economic proposals. Many of the Democrats elected to Congress in the aftermath of Watergate were more moderate than their predecessors who had been catechized in the New Deal gospel. These conservative Democrats sometimes partnered with Congressional Republicans to oppose Carter, most notably in response to the administration’s proposal for a federal office of consumer protection.

At a deeper level, Carter’s own temperamental and philosophical conservatism hamstrung the administration. Early in his first term, Carter began to worry about the size of the federal deficit and killed a tax rebate he had proposed and Congressional Democrats had embraced. The president’s comprehensive national urban policy veered to the right by transferring many programs to state and local governments, relying on privatization, and endorsing voluntarism and self-help. Organized labor felt abandoned by Carter, who remained cool to several of their highest legislative priorities. The president offered tepid support for national health insurance proposal and declined to lobby aggressively for a package of modest labor law reforms. The business community rallied to defeat the latter measure, in what AFL-CIO chief George Meany described as “an attack by every anti-union group in America to kill the labor movement.” ((George Meany quoted in Cowie, 293.)) In 1977 and 1978, liberal Democrats rallied behind the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment and Training Act, which promised to end unemployment through extensive government planning. The bill aimed not only to guarantee a job to every American but also to re-unite the interracial, working-class Democratic coalition that had been fractured by deindustrialization and affirmative action. “We must create a climate of shared interests between the needs, the hopes, and the fears of the minorities, and the needs, the hopes, and the fears of the majority,” wrote Senator Hubert Humphrey, Lyndon Johnson’s vice president and the bill’s co-sponsor. ((Hubert Humphrey quoted in Cowie, 268. )) Carter’s lack of enthusiasm for the proposal allowed conservatives from both parties to water down the bill to a purely symbolic gesture. Liberals, like labor leaders, came to regard the president as an unreliable ally.

Carter also came under fire from Republicans, especially the religious right. His administration incurred the wrath of evangelicals in 1978 when the Internal Revenue Service established new rules revoking the tax-exempt status of racially segregated, private Christian schools. The rules only strengthened a policy instituted by the Nixon administration; however, the religious right accused Carter of singling out Christian institutions. Republican activist Richard Viguerie described the IRS controversy as the “spark that ignited the religious right’s involvement in real politics.” ((Richard Viguerie, quoted in Joseph Crespino, “Civil Rights and the Religious Right,” in Bruce J. Schulman and Julian Zelizer, eds., Rightward Bound: Making America Conservative in the 1970s (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2008), 91. )) Race sat just below the surface of the IRS fight. After all, many of the schools had been founded to circumvent court-ordered desegregation. But the IRS ruling allowed the New Right to rain down fire on big government interference while downplaying the practice of racial exclusion at the heart of the case.

While the IRS controversy flared, economic crises multiplied. Unemployment reached 7.8% in May 1980, up from 6% at the start of Carter’s first term. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 148. )) Inflation (the rate at which the cost of good and services increases) jumped from 6% in 1978 to a staggering 20% by the winter of 1980. ((Judith Stein, Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2010), 231. )) In another bad omen, the iconic Chrysler Corporation appeared close to bankruptcy. The administration responded to these challenges in fundamentally conservative ways. First, Carter proposed a tax cut for the upper-middle class, which Congress passed in 1978. Second, the White House embraced a long-time goal of the conservative movement by deregulating the airline and trucking industries in 1978 and 1980, respectively. Third, Carter proposed balancing the federal budget—much to the dismay of liberals, who would have preferred that he use deficit spending to finance a new New Deal. Finally, to halt inflation, Carter turned to Paul Volcker, his appointee as Chair of the Federal Reserve. Volcker raised interest rates and tightened the money supply—policies designed to reduce inflation in the long run but which increased unemployment in the short run. Liberalism was on the run.

The “energy crisis” in particular brought out the Southern Baptist moralist in Carter. On July 15, 1979, the president delivered a nationally televised speech on energy policy in which he attributed the country’s economic woes to a “crisis of confidence.” Carter lamented that “too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption.” ((Jimmy Carter quoted in Chafe, 453. )) The president’s push to reduce energy consumption was reasonable, and the country’s initial response to the speech was favorable. Yet Carter’s emphasis on discipline and sacrifice, his spiritual diagnosis for economic hardship, sidestepped deeper questions of large-scale economic change and downplayed the harsh toll of inflation on regular Americans.

IV. The Election of 1980

These domestic challenges, combined with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the hostage crisis in Iran, hobbled Carter heading into his 1980 reelection campaign. Many Democrats were dismayed by his policies. The president of the International Association of Machinists dismissed Carter as “the best Republican President since Herbert Hoover.” ((William Winpisinger quoted in Cowie, 261. )) Angered by the White House’s refusal to back national health insurance, Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy challenged Carter in the Democratic primaries. Running as the party’s liberal standard-bearer and heir to the legacy of his slain older brothers, Kennedy garnered support from key labor unions and leftwing Democrats. He won the Michigan and Pennsylvania primaries—states where Democrats had embraced George Wallace eight years earlier. Carter ultimately vanquished Kennedy, but the close primary tally betrayed the president’s vulnerability.

Carter’s opponent in the general election was Ronald Reagan, who ran as a staunch fiscal conservative and a Cold War hawk. He vowed to reduce government spending and shrink the federal bureaucracy while eliminating the departments of Energy and Education that Carter created. As in his 1976 primary challenge to Gerald Ford, Reagan accused his opponent of failing to confront the Soviet Union. The GOP candidate vowed steep increases in military spending, and hammered Carter for canceling the B-1 bomber and signing the Panama Canal and Salt II treaties. Carter responded by labeling Reagan a warmonger, but events in Afghanistan and Iran discredited Carter’s foreign policy in the eyes of many Americans.

The incumbent fared no better on domestic affairs. Unemployment remained at nearly 8%. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 148. )) Meanwhile the Federal Reserve’s anti-inflation measures pushed interest rates to an unheard-of 18.5%. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 148. )) Reagan seized on these bad economic trends. On the campaign trail he brought down the house by proclaiming: “A recession is when your neighbor loses his job, and a depression is when you lose your job.” Reagan would then pause before concluding, “And a recovery is when Jimmy Carter loses his job.” ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 148. )) Carter reminded voters that his opponent opposed the creation of Medicare in 1965 and warned that Reagan would slash popular programs if elected. But the anemic economy prevented Carter’s blows from landing.

Social and cultural issues presented yet another challenge for the president. Despite Carter’s background as a “born-again” Christian and Sunday school teacher, he struggled to court the religious right. Carter scandalized devout Christians by admitting to lustful thoughts during an interview with Playboy magazine in 1976, telling the reporter he had “committed adultery in my heart many times.” ((Jimmy Carter quoted in “Carter Tells of ‘Adultery in His Heart,’” Los Angeles Times, September 21, 1976, B6. )) Although Reagan was only a nominal Christian and rarely attended church, the religious right embraced him. Reverend Jerry Falwell directed the full weight of the Moral Majority behind Reagan. The organization registered an estimated 2 million new voters in 1980. Ellen McCormack, the New York Catholic who ran for president as a Democrat on an anti-abortion platform in 1976, moved over to the GOP in 1980. Reagan also cultivated the religious right by denouncing abortion and endorsing prayer in school. The IRS tax exemption issue resurfaced as well, with the 1980 Republican platform vowing to “halt the unconstitutional regulatory vendetta launched by Mr. Carter’s IRS commissioner against independent schools.” ((Crespino, 103. )) Early in the primary season, Reagan condemned the policy during a speech at South Carolina’s Bob Jones University, which had recently sued the IRS after losing its tax-exempt status because of the fundamentalist institution’s ban on interracial dating.

Jerry Falwell, the wildly popular TV evangelist, founded the Moral Majority political organization in the late 1970s. Decrying the demise of the nation’s morality, the organization gained a massive following, helping to cement the status of the New Christian Right in American politics. Photograph, date unknown. Wikimedia.

Reagan’s campaign appealed subtly but unmistakably to the racial hostilities of white voters. The candidate held his first post-nominating convention rally at the Neshoba Count Fair near Philadelphia, Mississippi, the town where three civil rights workers had been murdered in 1964. In his speech, Reagan championed the doctrine of states rights, which had been the rallying cry of segregationists in the 1950s and 1960s. In criticizing the welfare state, Reagan had long employed thinly veiled racial stereotypes about a “welfare queen” in Chicago who drove a Cadillac while defrauding the government or a “strapping young buck” purchasing T-bone steaks with food stamps. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 163; Jon Nordheimer, “Reagan is Picking His Florida Spots: His Campaign Aides Aim for New G.O.P. Voters in Strategic Areas,” New York Times, February 5, 1976, 24. )) Like George Wallace before him, Reagan exploited the racial and cultural resentments of struggling white working-class voters. And like Wallace, he attracted blue-collar workers in droves.

With the wind at his back on almost every issue, Reagan only needed to blunt Carter’s characterization of him as an angry extremist. Reagan did so during their only debate by appearing calm and amiable. “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” he asked the American people at the conclusion of the debate. ((Sean Wilentz, The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974-2008 (New York: Harper Collins, 2008), 124.)) The answer was no. Reagan won the election with 51% of the popular vote to Carter’s 41%. (Independent John Anderson captured 7%.) ((Meg Jacobs and Julian Zelizer, Conservatives in Power: The Reagan Years, 1981-1989: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011), 2.)) Despite capturing only a slim majority, Reagan scored a decisive 489-49 victory in the Electoral College. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 150.)) Republicans gained control of the Senate for the first time since 1955 by winning 12 seats. Liberal Democrats George McGovern, Frank Church, and Birch Bayh went down in defeat, as did liberal Republican Jacob Javits. The GOP picked up 33 House seats, narrowing the Democratic advantage in the lower chamber. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 150.)) The New Right had arrived in Washington, DC.

V. The New Right in Power

Harkening back to Jeffersonian politics of limited government, a viewpoint that would only increase in popularity over the next three decades, Ronald Reagan launched his campaign by saying bluntly, “I believe in states’ rights.” Reagan secured the presidency through appealing to the growing conservatism of much of the country. Ronald Reagan and wife Nancy Reagan waving from the limousine during the Inaugural Parade in Washington, D.C. on Inauguration Day, 1981. Wikimedia.

In his first inaugural address Reagan proclaimed that “government is not the solution to the problem, government is the problem.” ((Ronald Reagan quoted in Jacobs and Zelizer, 20.)) In reality, Reagan focused less on eliminating government than on redirecting government to serve new ends. In line with that goal, his administration embraced “supply-side” economic theories that had recently gained popularity among the New Right. While the postwar gospel of Keynesian economics had focused on stimulating consumer demand, supply-side economics held that lower personal and corporate tax rates would encourage greater private investment and production. The resulting wealth would “trickle down” to lower-income groups through job creation and higher wages. Conservative economist Arthur Laffer predicted that lower tax rates would generate so much economic activity that federal tax revenues would actually increase. The administration touted the so-called “Laffer Curve” as justification for the tax cut plan that served as the cornerstone of Reagan’s first year in office. Keynesian logic viewed tax cuts as inflationary, stifling the economy. But Republican Congressman Jack Kemp, an early supply-side advocate and co-sponsor of Reagan’s tax bill, promised that it would unleash the “creative genius that has always invigorated America.” ((Jack Kemp quoted in Jacobs and Zelizer, 21.))

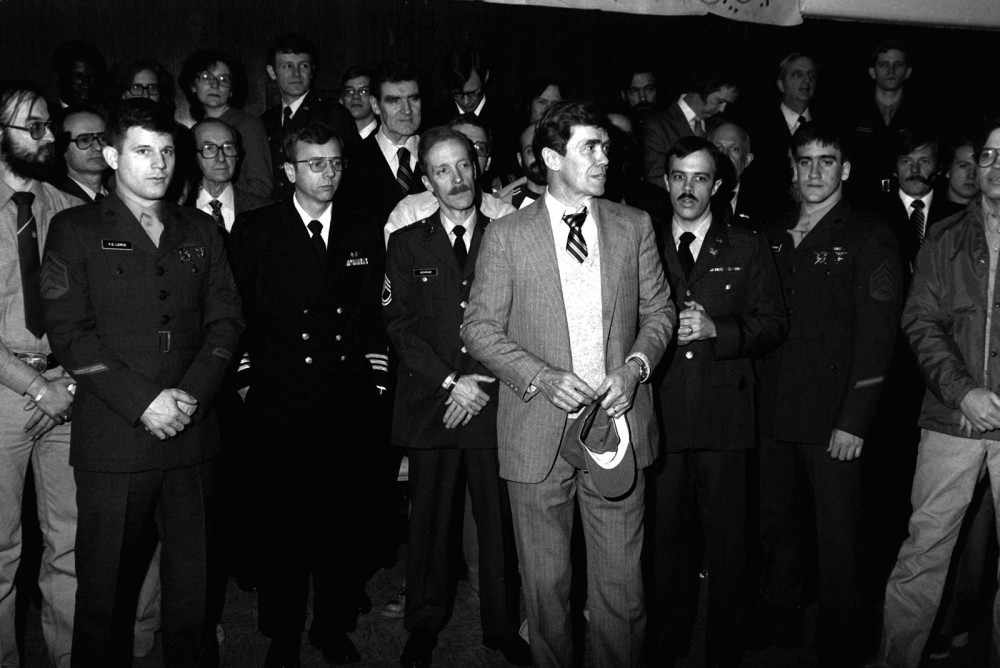

The Iranian hostage crisis ended literally during President Reagan’s inauguration speech. By a coincide of timing, then, the Reagan administration received credit for ending the conflict. This group photograph shows the former hostages in the hospital before being released back to the U.S. Johnson Babela, Photograph, 1981. Wikimedia.

The tax cut faced early skepticism from Democrats and even some Republicans. Vice president George H.W. Bush had belittled supple-side theory as “voodoo economics” during the 1980 Republican primaries. ((Wilentz, 121.)) But a combination of skill and serendipity pushed the bill over the top. Reagan aggressively and effectively lobbied individual members of Congress for support on the measure. Then on March 30, 1981, Reagan survived an assassination attempt by a mentally unstable young man named John Hinckley. Public support swelled for the hospitalized president. Congress ultimately approved a $675-billion tax cut in July 1981 with significant Democratic support. The bill reduced overall federal taxes by more than one quarter and lowered the top marginal rate from 70% to 50%, with the bottom rate dropping from 14% to 11%. It also slashed the rate on capital gains from 28% to 20%. ((Jacobs and Zelizer, 25-26. )) The next month, Reagan scored another political triumph in response to a strike called by the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO). During the 1980 campaign, Reagan had wooed organized labor, describing himself as “an old union man” (he had led the Screen Actor’s Guild from 1947 to 1952) who still held Franklin Roosevelt in high regard. ((Ronald Reagan quoted in Steve Neal, “Reagan Assails Carter On Auto layoffs,” Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1980, 5)) PATCO had been one of the few labor unions to endorse Reagan. Nevertheless, the president ordered the union’s striking air traffic controllers back to work and fired more than 11,000 who refused. Reagan’s actions crippled PATCO and left the American labor movement reeling. For the rest of the 1980s the economic terrain of the United States—already unfavorable to union organizing—shifted decisively in favor of employers. The unionized portion of the private-sector workforce fell from 20% in 1980 to 12% in 1990. ((Stein, 267. )) Reagan’s defeat of PATCO and his tax bill enhanced the economic power of corporations and high-income households; the conflicts confirmed that a conservative age had dawned in American workplaces and in politics.

The new administration appeared to be flying high in the fall of 1981, but other developments challenged the rosy economic forecasts emanating from the White House. As Reagan ratcheted up tension with the Soviet Union, Congress approved his request for $1.2 trillion in new military spending. ((Chafe, 474. )) Contrary to the assurances of David Stockman—the young supply-side disciple who headed the Office of Management and Budget—the combination of lower taxes and higher defense budgets caused the national debt to balloon. By the end of Reagan’s first term it equaled 53% of GDP, as opposed to 33% in 1981. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 159.)) The increase was staggering, especially for an administration that had promised to curb spending. Meanwhile, Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker continued his policy from the Carter years of combating inflation by maintain high interest rates, which surpassed 20% in June 1981. ((Gil Troy, Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 67.)) The Fed’s action increased the cost of borrowing money and stifled economic activity.

As a result, the United States experienced a severe economic recession in 1981 and 1982. Unemployment rose to nearly 11%, the highest figure since the Great Depression. ((Chafe, 476.)) Reductions in social welfare spending heightened the impact of the recession on ordinary people. Congress had followed Reagan’s lead by reducing funding for food stamps and Aid to Families with Dependent Children, eliminated the CETA program and its 300,000 jobs, and removed a half-million people from the Supplemental Social Security program for the physically disabled. ((Chafe, 474.)) The cuts exacted an especially harsh toll on low-income communities of color. The head of the NAACP declared the administration’s budget cuts had rekindled “war, pestilence, famine, and death.” ((Margaret Bush Wilson quoted in Troy, 93.)) Reagan also received bipartisan rebuke in 1981 after proposing cuts to Social Security benefits for early retirees. The Senate voted unanimously to condemn the plan, and Democrats framed it as a heartless attack on the elderly. Confronted with recession and harsh public criticism, a chastened White House worked with Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neil in 1982 on a bill that restored $98 billion of the previous year’s tax cuts. ((Troy, 210.)) Despite compromising with the administration on taxes, Democrats railed against the so-called “Reagan Recession,” arguing that the president’s economic policies favored the most fortunate Americans. This appeal, which Democrats termed the “fairness issue,” helped them win 26 House seats in the autumn Congressional races. ((Troy, 110.)) The New Right appeared to be in trouble.

VI. Morning in America

Reagan nimbly adjusted to the political setbacks of 1982. Following the rejection of his Social Security proposals, Reagan appointed a bipartisan panel to consider changes to the program. In early 1983, the commission recommended a one-time delay in cost-of-living increases, a new requirement that government employees pay into the system, and a gradual increase in the retirement age from 65 to 67. The commission also proposed raising state and federal payroll taxes, with the new revenue poured into a trust fund that would transform Social Security from a pay-as-you-go system to one with significant reserves. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 163-164. )) Congress quickly passed the recommendations into law, allowing Reagan to take credit for strengthening a program cherished by most Americans. The president also benefited from an economic rebound. Real disposable income rose 2.5% in 1983 and 5.8% the following year. ((Troy, 208. )) Unemployment dropped to 7.5% in 1984. ((Chafe, 477. )) Meanwhile, the “harsh medicine” of high interest rates helped lower inflation to 3.5%. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 162. Many people used the term “harsh medicine” to describe Volcker’s action on interest rates, see Art Pine, “Letting Harsh Medicine Work,” Washington Post, October 14, 1979, G1. )) While campaigning for reelection in 1984, Reagan pointed to the improving economy as evidence that it was “morning again in America.” ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 189. )) His personal popularity soared. Most conservatives ignored the debt increase and tax hikes of the previous two years and rallied around the president.

The Democratic Party, on other hand, stood at an ideological crossroads in 1984. The favorite to win the party’s nomination was Walter Mondale, who had been a staunch ally of organized labor and civil rights as a senator during the 1960s and 1970s. He later served as Jimmy Carter’s vice president. Mondale’s chief rivals were civil rights activist Jesse Jackson and Colorado Senator Gary Hart, one of the young Democrats elected to Congress in 1974 following Nixon’s downfall. Hart and other “Watergate babies” still identified as liberals but rejected their party’s faith in activist government and embraced market-based approaches to policy issues. In so doing, they conceded significant political ground to supply-siders and conservative opponents of the welfare state. Many Democrats, however, were not prepared to abandon their New Deal inheritance. The ideological tension within the party played out in the 1984 primary campaign. Jackson offered a largely progressive program but won only two states. Hart’s platform—economically moderate but socially liberal—inverted the political formula of Mondale’s New Deal-style liberalism. Throughout the primaries, Hart contrasted his “new ideas” with Mondale’s “old-fashioned” politics. Mondale eventually secured his party’s nomination but suffered a crushing defeat in the general election. Reagan captured 49 of 50 states, winning 58.8% of the popular vote. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 189.))

Mondale’s loss seemed to confirm that the new breed of moderate Democrats better understood the mood of the American people. The future of the party belonged to post-New Deal liberals like Hart and to the constituency that supported him in the primaries: upwardly mobile, white professionals and suburbanites. In February 1985, a group of centrists formed the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) as a vehicle for distancing the party from organized labor and Keynesian economics while cultivating the business community. Jesse Jackson dismissed the DLC as “Democrats for the Leisure Class,” but the organization included many of the party’s future leaders, including Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 190-191.)) The formation of the DLC illustrated the degree to which to the New Right had transformed American politics.

Reagan entered his second term with a much stronger mandate than in 1981, but the GOP makeover of Washington, DC stalled. The Democrats regained control of the Senate in 1986 (Republicans maintained a majority in the House,) Democratic opposition prevented Reagan from eliminating means-tested social welfare programs; however, Congress failed to increase benefit levels for welfare programs or raise the minimum wage, decreasing the real value of those benefits. Democrats and Republicans occasionally fashioned legislative compromises, as with the Tax Reform Act of 1986. The bill lowered the top corporate tax rate from 46% to 34% and reduced the highest marginal rate from 50% to 28%, while also simplifying the tax code and eliminating numerous loopholes. ((Troy, 210; Patterson, Restless Giant, 165.)) Both parties—as well as the White House—claimed credit for the bargain and celebrated the bill as a significant achievement. The steep cuts to the corporate and individual rates certainly benefited wealthy individuals, but the legislation made virtually no net change to federal revenues. In 1986, Reagan also signed into law the Immigration Reform and Control Act. American policymakers hoped to do two things: deal with the millions of undocumented immigrants already in the United States while simultaneously choking off future unsanctioned migration. The former goal was achieved (nearly three million undocumented workers received legal status) but the latter proved elusive.

One of Reagan’s most far-reaching victories occurred through judicial appointments. He named 368 district and federal appeals court judges during his two terms. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 173-174.)) Observers noted that almost all of the appointees were white men. (Seven were African American, fifteen were Latino, and two were Asian American.) Reagan also appointed three Supreme Court justices: Sandra Day O’Connor, who to the dismay of the religious right turned out to be a moderate; Anthony Kennedy, a solidly conservative Catholic who occasionally sided with the court’s liberal wing; and arch-conservative Antonin Scalia. The New Right’s transformation of the judiciary had limits. In 1987, Reagan nominated Robert Bork to fill a vacancy on the Supreme Court. Bork, a federal judge and former Yale University law professor, was a staunch conservative. He had opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, affirmative action, and the Roe v. Wade decision. After acrimonious confirmation hearings, the Senate rejected Bork’s nomination by a vote of 58-42. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 171. ))

VII. African American Life in Reagan’s America

African Americans read Bork’s nomination as another signal of the conservative movement’s hostility to their social, economic, and political aspirations. Indeed, Ronald Reagan’s America presented African Americans with a series of contradictions. Blacks achieved significant advances in politics, culture, and socio-economic status. African Americans continued a trend from the late 1960s and 1970s by gaining control of major municipal governments across the country during the 1980s. In 1983, voters in Philadelphia and Chicago elected Wilson Goode and Harold Washington, respectively, as their cities’ first black mayors. At the national level, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson became the first African American man to run for president when he campaigned for the Democratic Party’s nomination in 1984 and 1988. Propelled by chants of “Run, Jesse, Run,” Jackson achieved notable success in 1988, winning nine state primaries and finishing second with 29% of the vote. ((1988 Democratic Primaries, CQ Voting and Elections Collection, database accessed June 30, 2015.))

![Jesse Jackson was only the second African American to mount a national campaign for the presidency. His work as a civil rights activist and Baptist minister garnered him a significant following in the African American community, but never enough to secure the Democratic nomination. His Warren K. Leffler, “IVU w/ [i.e., interview with] Rev. Jesse Jackson,” July 1, 1983. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003688127/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/01277v-983x1500.jpg)

Jesse Jackson was only the second African American to mount a national campaign for the presidency. His work as a civil rights activist and Baptist minister garnered him a significant following in the African American community, but never enough to secure the Democratic nomination. His Warren K. Leffler, “IVU w/ [i.e., interview with] Rev. Jesse Jackson,” July 1, 1983. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003688127/.

VIII. Bad Times and Good Times

Working- and middle-class Americans, especially those of color, struggled to maintain economic equilibrium during the Reagan years. The growing national debt generated fresh economic pain. The federal government borrowed money to finance the debt, raising interest rates to heighten the appeal of government bonds. Foreign money poured into the United States, raising the value of the dollar and attracting an influx of goods from overseas. The imbalance between American imports and exports grew from $36 billion in 1980 to $170 billion in 1987. ((Chafe, 487. )) Foreign competition battered the already anemic manufacturing sector. The appeal of government bonds likewise drew investment away from American industry.

Continuing an ongoing trend, many steel and automobile factories in the industrial Northeast and Midwest closed or moved overseas during the 1980s. Bruce Springsteen, the bard of blue-collar America, offered eulogies to Rust Belt cities in songs like “Youngstown” and “My Hometown,” in which the narrator laments that his “foreman says these jobs are going boys/and they ain’t coming back.” ((Bruce Springsteen, “My Hometown,” Born in the USA (Columbia Records: New York, 1984).)) Competition from Japanese carmakers spurred a “Buy American” campaign but also caused flare-ups of violent xenophobia. In 1982, two autoworkers in suburb Detroit fatally bludgeoned Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American engineer they reportedly mistook for Japanese. Chin’s murder was extreme, but economic strain caused social tension throughout the industrial heartland. Meanwhile, a “farm crisis” gripped the rural United States. Expanded world production meant new competition for American farmers, while soaring interest rates caused the already sizable debt held by family farms to mushroom. Farm foreclosures skyrocketed during Reagan’s tenure. In September 1985 prominent musicians including Neil Young and Willie Nelson organized “Farm Aid,” a benefit concert at the University of Illinois’s football stadium designed to raise money for struggling farmers.

At the other end of the economic spectrum, wealthy Americans thrived thanks to the policies of the New Right. The financial industry found new ways to earn staggering profits during the Reagan years. Wall Street brokers like “junk bond king” Michael Milken reaped fortunes selling high-risk, high-yield securities. Reckless speculation helped drive the stock market steadily upward until the crash of October 19, 1987. On “Black Friday,” the market plunged 800 points, erasing 13% of its value. Investors lost more than $500 billion. ((Chafe, 489. )) An additional financial crisis loomed in the savings and loan industry, and Reagan’s deregulatory policies bore significant responsibility. In 1982 Reagan signed a bill increasing the amount of federal insurance available to savings and loan depositors, making those financial institutions more popular with consumers. The bill also allowed “S & L’s” to engage in high-risk loans and investments for the first time. Many such deals failed catastrophically, while some S &L managers brazenly stole from their institutions. In the late 1980s, S & L’s failed with regularity, and ordinary Americans lost precious savings. The 1982 law left the government responsible for bailing out S&L’s out at an eventual cost of $132 billion. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 175. ))

IX. Culture Wars of the 1980s

Popular culture of the 1980s offered another venue in which conservatives and liberals waged a battle of ideas. Reagan’s militarism and patriotism pervaded movies like Top Gun and the Rambo series, starring Sylvester Stallone as a Vietnam War veteran haunted by his country’s failure to pursue victory in Southeast Asia. In contrast, director Olive Stone offered searing condemnations of the war in Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July. Television shows like Dynasty and Dallas celebrated wealth and glamour, reflecting the pride in conspicuous consumption that emanated from the White House and corporate boardrooms during the decade. At the same time, films like Wall Street and novels like Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero skewered the excesses of the rich. Yet the most significant aspect of 1980s’ popular culture was its lack of politics altogether. Rather, Steven Spielberg’s E.T: The Extra-Terrestrial and his Indiana Jones adventure trilogy topped the box office. Cinematic escapism replaced the serious social examinations of 1970s’ film. Quintessential Hollywood leftist Jane Fonda appeared frequently on television but only to peddle exercise videos.

New forms of media changed the ways in which people experienced popular culture. In many cases, this new media contributed to the privatization of life, as people shifted focus from public spaces to their own homes. Movie theaters faced competition from the videocassette recorder (VCR), which allowed people to watch films (or exercise with Jane Fonda) in the privacy of their living room. Arcades gave way to home video game systems. Personal computers proliferated, a trend spearheaded by the Apple Company and its Apple II computer. Television viewership—once dominated by the “big three” networks of NBC, ABC, and CBS—fragmented with the rise of cable channels that catered to particular tastes. Few cable channels so captured the popular imagination as MTV, which debuted in 1981. Telegenic artists like Madonna, Prince, and Michael Jackson skillfully used MTV to boost their reputations and album sales. Conservatives condemned music videos for corrupting young people with vulgar, anti-authoritarian messages, but the medium only grew in stature. Critics of MTV targeted Madonna in particular. Her 1989 video “Like a Prayer” drew protests for what some people viewed as sexually suggestive and blasphemous scenes. The religious right increasingly perceived popular culture as hostile to Christian values.

The Apple II computer, introduced in 1977, was the first successful mass-produced microcomputer meant for home use. Rather clunky-looking to our twenty-first-century eyes, this 1984 version of the Apple II was the smallest and sleekest model yet introduced. Indeed, it revolutionized both the substance and design of personal computers. Photograph of the Apple iicb. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apple_iicb.jpg.

Cultural battles were even more heated in the realm of gender and sexual politics. American women pushed farther into male-dominated spheres during the 1980s. By 1984, women in the workforce outnumbered those who worked at home. ((Ruth Rosen, The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America (New York: Penguin Books, 2000), 337. )) That same year, New York Representative Geraldine Ferraro became the first women to run on a major party’s presidential ticket when Democratic candidate Walter Mondale named her his running mate. Yet the triumph of the right placed fundamental questions about women’s rights near the center of American politics–particularly in regard to abortion. The issue increasingly divided Americans. Pro-life Democrats and pro-choice Republicans grew rare, as the National Abortion Rights Action League enforced pro-choice orthodoxy on the left and the National Right to Life Commission did the same with pro-life orthodoxy on the right. Religious conservatives took advantage of the Republican takeover of the White House and Senate in 1980 to push for new restrictions on abortion—with limited success. Senators Jesse Helms of North Carolina and Orrin Hatch of Utah introduced versions of a “Human Life Amendment” to the U.S. Constitution that defined life as beginning at conception; their efforts failed, though in 1982 Hatch’s amendment came within 18 votes of passage in the Senate. ((Self, 376-377. )) Reagan, more interested in economic issues than social ones, provided only lukewarm support for these efforts. He further outraged anti-abortion activists by appointing Sandra Day O’Connor, a supporter of abortion rights, to the Supreme Court. Despite these setbacks, anti-abortion forces succeeded in defunding some abortion providers. The 1976 Hyde Amendment prohibited the use of federal funds to pay for abortions; by 1990 almost every state had its own version of the Hyde Amendment. Yet some anti-abortion activists demanded more. In 1988 evangelical activist Randall Terry founded Operation Rescue, an organization that targeted abortion clinics and pro-choice politicians with confrontational—and sometimes violent—tactics. Operation Rescue demonstrated that the fight over abortion would grow only more heated in the 1990s.

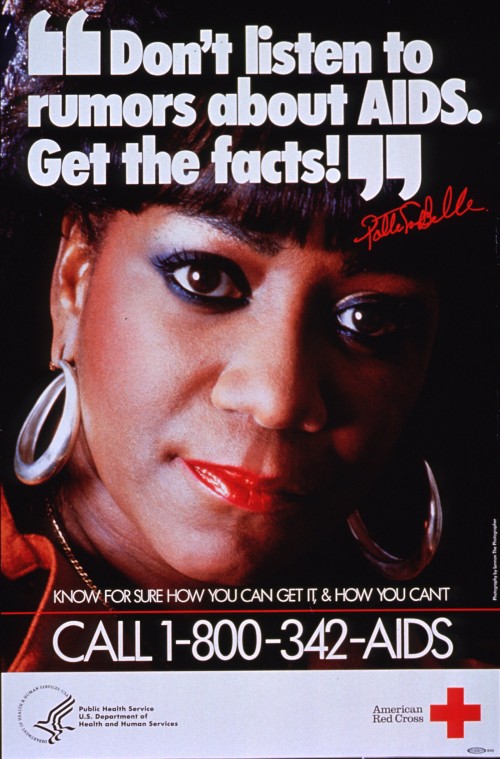

The emergence of a deadly new illness, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), simultaneously devastated, stigmatized, and energized the nation’s homosexual community. When AIDS appeared in the early 1980s, most of its victims were gay men. For a time the disease was known as GRID—Gay-Related Immunodeficiency Disorder. The epidemic rekindled older pseudo-scientific ideas about inherently diseased nature of homosexual bodies. The Reagan administration met the issue with indifference, leading liberal Congressman Henry Waxman to rage that “if the same disease had appeared among Americans of Norwegian descent…rather than among gay males, the response of both the government and the medical community would be different.” ((Self, 387-388. )) Some religious figures seemed to relish the opportunity to condemn homosexual activity; Catholic columnist Patrick Buchanan remarked that “the sexual revolution has begun to devour its children.” ((Self, 384. ))

Homosexuals were left to forge their own response to the crisis. Some turned to confrontation—like New York playwright Larry Kramer. Kramer founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, which demanded a more proactive response to the epidemic. Others sought to humanize AIDS victims; this was the goal of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, a commemorative project begun in 1985. By the middle of the decade the federal government began to address the issue haltingly. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, an evangelical Christian, called for more federal funding on AIDS-related research, much to the dismay of critics on the religious right. By 1987 government spending on AIDS-related research reached $500 million—still only 25% of what experts advocated. ((Self, 389. )) In 1987 Reagan convened a presidential commission on AIDS; the commission’s report called for anti-discrimination laws to protect AIDS victims and for more federal spending on AIDS research. The shift encouraged activists. Nevertheless, on issues of abortion and gay rights—as with the push for racial equality—activists spent the 1980s preserving the status quo rather than building on previous gains. This amounted to a significant victory for the New Right.

The AIDS epidemic hit the gay and African American communities particularly hard in the 1980s, prompting awareness campaigns by celebrities like Patti LaBelle. Poster, c. 1980s. Wikimedia.

X. The New Right Abroad

If the conservative movement recovered lost ground on the field on gender and sexual politics, it captured the battlefield on American foreign policy in the 1980s–for a time, at least. Ronald Reagan entered office a committed Cold Warrior. He held the Soviet Union in contempt, denouncing it in a 1983 speech as an “evil empire.” ((Wilentz, 163. )) And he never doubted that the Soviet Union would end up “on the ash heap of history,” as he said in a 1982 speech to the British Parliament. ((Lou Cannon, “President Calls for ‘Crusade’: Reagan Proposes Plan to Counter Soviet Challenge,” Washington Post, June 9, 1982, A1. )) Indeed, Reagan believed it was the duty of the United States to speed the Soviet Union to its inevitable demise. His “Reagan Doctrine” declared that the United States would supply aid to anti-communist forces everywhere in the world. ((Conservative newspaper columnist Charles Krauthammer coined the phrase. See Wilentz, 157. )) To give this doctrine force, Reagan oversaw an enormous expansion in the defense budget. Federal spending on defense rose from $171 billion in 1981 to $229 billion in 1985, the highest level since the Vietnam War. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 205. )) He described this as a policy of “peace through strength,” a phrase that appealed to Americans who, during the 1970s, feared that the United States was losing its status as the world’s most powerful nation. Yet the irony is that Reagan, for all his militarism, helped bring the Cold War to an end. He achieved it not through nuclear weapons but through negotiation, a tactic he had once scorned.

Reagan’s election came at a time when many Americans feared their country was in an irreversible decline. American forces withdrew in disarray from South Vietnam in 1975. The United States returned control of the Panama Canal to Panama in 1978, despite protests from conservatives. Pro-American dictators were toppled in Iran and Nicaragua in 1979. The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan that same year, leading conservatives to warn about American weakness in the face of Soviet expansion. Such warnings were commonplace in the 1970s. “Team B,” a group of intellectuals commissioned by the CIA to examine Soviet capabilities, released a report in 1976 stating that “all evidence points to an undeviating Soviet commitment to…global Soviet hegemony.” (( “Intelligence Community Experiment in Competitive Analysis: Soviet Strategic Objectives: An Alternative View,” Report of Team B, National Security Archive, George Washington University, http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB139/nitze10.pdf, accessed June 30, 2015. )) The Committee on the Present Danger, an organization of conservative foreign policy experts, issued similar statements. When Reagan warned, as he did in 1976, that “this nation has become Number Two in a world where it is dangerous—if not fatal—to be second best,” he was speaking to these fears of decline. ((Laura Kalman, Right Star Rising: A New Politics, 1974-1980 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010), 166-167. ))

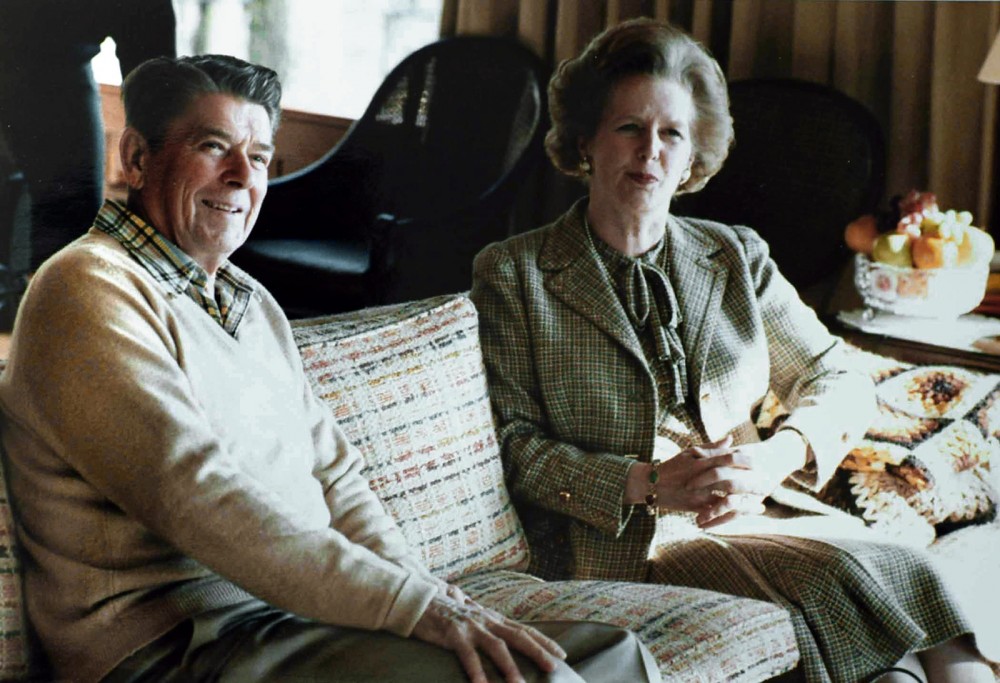

Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, leaders of two of the world’s most powerful countries, formed an alliance that benefited both throughout their tenures in office. Photograph of Margaret Thatcher with Ronald Reagan at Camp David, December 22, 1984. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thatcher_Reagan_Camp_David_sofa_1984.jpg.

The Reagan administration made Latin America a showcase for its newly assertive policies. Jimmy Carter had sought to promote human rights in the region, but Reagan and his advisers scrapped this approach and instead focused on fighting communism—a term they applied to all Latin American left-wing movements. Reagan justified American intervention by pointing out Latin America’s proximity to the United States: “San Salvador [in El Salvador] is closer to Houston, Texas, than Houston is to Washington, DC,” he said in one speech, adding, “Central America is America.” And so when communists with ties to Cuba overthrew the government of the Caribbean nation of Grenada in October 1983, Reagan dispatched the United States Marines to the island. Dubbed “Operation Urgent Fury,” the Grenada invasion overthrew the leftist government after less than a week of fighting. Despite the relatively minor nature of the mission, its success gave victory-hungry Americans something to cheer about after the military debacles of the previous two decades.

Operation Urgent Fury, the U.S. invasion of Grenada, was broadly supported by the U.S. public. This photograph shows the deployment of U.S. Army Rangers into Grenada. Photograph, October 25, 1983. Wikimedia.

Grenada was the only time Reagan deployed the American military in Latin America, but the United States also influenced the region by supporting rightwing, anti-communist movements there. From 1981 to 1990, the United States gave more than $4 billion to the government of El Salvador in a largely futile effort to defeat the guerillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). ((Ronald Reagan, “Address to the Nation on United States Policy in Central America,” May 9, 1984. http://www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/speeches/1984/50984h.htm. Accessed June 30, 2015. )) Salvadoran security forces equipped with American weapons committed numerous atrocities, including the slaughter of almost 1,000 civilians at the village of El Mozote in December 1981. The United States also supported the contras, a right-wing insurgency fighting the leftist Sandinista government in Nicaragua. Reagan, overlooking the contras’ brutal tactics, hailed them as the “moral equivalent of the Founding Fathers.” ((Ronald Reagan, “Remarks at the Annual Dinner of the Conservative Political Action Conference,” March 1, 1985. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=38274. Accessed June 30, 2015.))

The Reagan administration took a more cautious approach in the Middle East, where its policy was determined by a mix of anti-communism and hostility to the Islamic government of Iran. When Iraq invaded Iran in 1980, the United States supplied Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein with military intelligence and business credits—even after it became clear that Iraqi forces were using chemical weapons. Reagan’s greatest setback in the Middle East came in 1982, when, shortly after Israel invaded Lebanon, he dispatched Marines to the Lebanese city of Beirut to serve as a peacekeeping force. On October 23, 1983, a suicide bomber killed 241 Marines stationed in Beirut. Congressional pressure and anger from the American public forced Reagan to recall the Marines from Lebanon in March 1984. Reagan’s decision demonstrated that, for all his talk of restoring American power, he took a pragmatic approach to foreign policy. He was unwilling to risk another Vietnam by committing American troops to Lebanon.

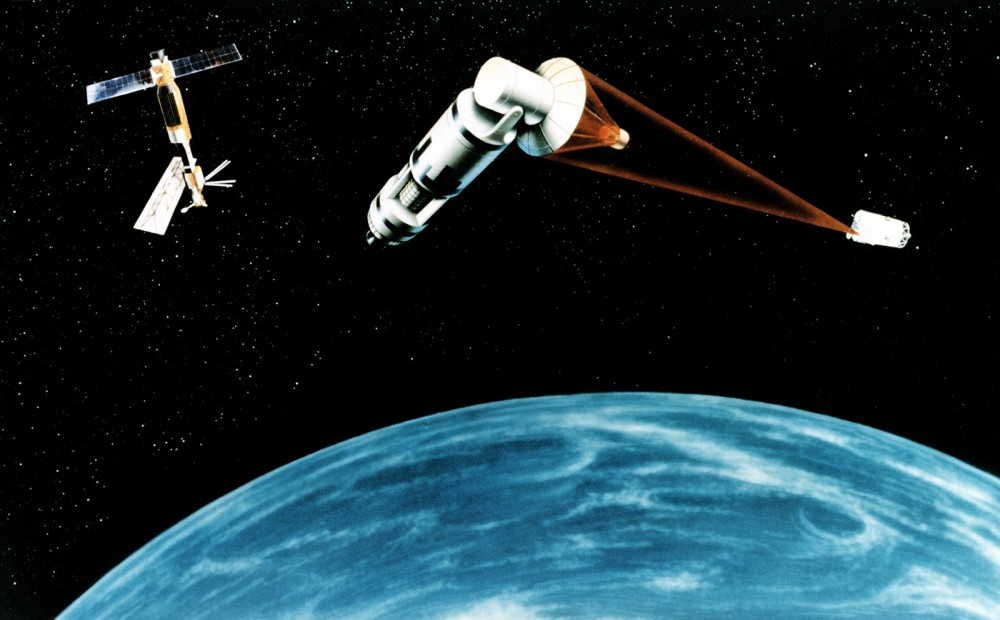

Though Reagan’s policies toward Central America and the Middle East aroused protest, it was his policy on nuclear weapons that generated the most controversy. Initially Reagan followed the examples of presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter by pursuing arms limitation talks with the Soviet Union. American officials participated in the Intermediate-range Nuclear Force Talks (INF) that began in 1981 and Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) in 1982. But the breakdown of these talks in 1983 led Reagan to proceed with plans to place Pershing II nuclear missiles in Western Europe to counter Soviet SS-20 missiles in Eastern Europe. Reagan went a step further in March 1983, when he announced plans for a “Strategic Defense Initiative,” a space-based system that could shoot down incoming Soviet missiles. Critics derided the program as a “Star Wars” fantasy, and even Reagan’s advisors harbored doubts. “We don’t have the technology to do this,” Secretary of State George Shultz told aides. ((Frances Fitzgerald, Way Out There in the Blue: Reagan, Star Wars, and the End of the Cold War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), 205. )) These aggressive policies fed a growing “nuclear freeze” movement throughout the world. In the United States, organizations like the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy organized protests that culminated in a June 1982 rally that drew almost a million people to New York City’s Central Park.

President Reagan proposed space- and ground-based systems to protect the United States from nuclear missiles in his 1984 Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). Scientists argued it was unrealistic or impossible with contemporary technology, and it was lambasted in the media as “Star Wars.” Indeed, as this artist’s representation of SDI shows, it was rather ridiculous. Created October 18, 1984. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Space_Laser_Satellite_Defense_System_Concept.jpg.

Protests in the streets were echoed by resistance in Congress. Congressional Democrats opposed Reagan’s policies on the merits; congressional Republicans, though they supported Reagan’s anti-communism, were wary of the administration’s fondness for circumventing Congress. In 1982 the House voted 411-0 to approve the Boland Amendment, which barred the United States from supplying funds to overthrow Nicaragua’s Sandinista government. A second Boland Amendment in 1984 prohibited any funding for the anti-Sandinista contra movement. The Reagan administration’s determination to flout these amendments led to a scandal that almost destroyed Reagan’s presidency. Robert MacFarlane, the president’s National Security Advisor, and Oliver North, a member of the National Security Council, raised money to support the contras by selling American missiles to Iran and funneling the money to Nicaragua. When their scheme was revealed in 1986, it was hugely embarrassing for Reagan. The president’s underlings had not only violated the Boland Amendments but had also, by selling arms to Iran, made a mockery of Reagan’s declaration that “America will never make concessions to the terrorists.” But while the Iran-Contra affair generated comparisons to the Watergate scandal, investigators were never able to prove Reagan knew about the operation. Without such a “smoking gun,” talk of impeaching Reagan remained simply talk.

Though the Iran-Contra scandal tarnished the Reagan administration’s image, it did not derail Reagan’s most significant achievement: easing tensions with the Soviet Union. This would have seemed impossible in Reagan’s first term, when the president exchanged harsh words with a rapid succession of Soviet leaders—Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov, and Konstantin Chernenko. In 1985, however, the aged Chernenko’s unsurprising death handed leadership of the Soviet Union to Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev, a true believer in socialism, nonetheless realized that the Soviet Union desperately needed to reform its stolid Stalinism. He instituted a program of perestroika, which referred to the restructuring of the Soviet system, and of glasnost, which meant greater transparency in government. Gorbachev also reached out to Reagan in hopes of negotiating an end the arms race that was bankrupting the Soviet Union. Reagan and Gorbachev met in Geneva, Switzerland in 1985 and Reykjavik, Iceland in 1986. The summits failed any concrete agreements—largely thanks to Reagan’s refusal to limit the Strategic Defense Initiative. But the two leaders developed a relationship unprecedented in the history of US-Soviet relations. This trust made possible the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty of 1987, which committed both sides to a sharp reduction in their nuclear arsenal.

By the late 1980s the Soviet empire was crumbling. Some credit must go to Reagan, who successfully combined anti-communist rhetoric (such as his 1987 speech at the Berlin Wall, where he declared, “General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace…tear down this wall!”) with a willingness to negotiate with Soviet leadership. ((Lou Cannon, “Reagan Challenges Soviets To Dismantle Berlin Wall: Aides Disappointed at Crowd’s Lukewarm Reception,” Washington Post, June 13, 1987, A1. )) But most significant causes of collapse lay within the Soviet empire itself. Soviet-allied governments in Eastern Europe tottered under pressure from dissident organizations like Poland’s Solidarity and East Germany’s Neues Forum. Some of these countries, such as Poland, were also pressured from within by the Roman Catholic Church, which had turned toward active anti-communism under Pope John Paul II. When Gorbachev made it clear that he would not send the Soviet military to prop up these regimes, they collapsed one by one in 1989—in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and East Germany. Within the Soviet Union, Gorbachev’s proposed reforms unraveled the decaying Soviet system rather than bringing stability. By 1991 the Soviet Union itself had vanished, dissolving into a “Commonwealth of Independent States.”

XI. Conclusion

Reagan left office in 1988 with the Cold War waning and the economy booming. Unemployment had dipped to 5% by 1988. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 163.)) Between 1981 and 1986, gas prices fell from $1.38 per gallon to 95¢. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 163. )) The stock market recovered from the crash, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average—which stood at 950 in 1981—reached 2,239 by the end of Reagan’s second term. ((Patterson, Restless Giant. )) Yet, the economic gains of the decade were unequally distributed. The top fifth of households enjoyed rising incomes while the rest stagnated or declined. ((Jacobs and Zelizer, 32. )) In constant dollars, annual CEO pay rose from $3 million in 1980 to roughly $12 million during Reagan’s last year in the White House. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 186. )) Between 1985 and 1989 the number of Americans living in poverty remained steady at 33 million. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 164. )) Real per capita money income grew at only 2% per year, a rate roughly equal to the Carter years. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 166. )) The American economy saw more jobs created than lost during the 1980s, but half of the jobs eliminated were in high-paying industries. ((Chafe, 488. )) Furthermore, half of the new jobs failed to pay wages above the poverty line. The economic divide was most acute for African Americans and Latinos, one-third of whom qualified as poor. Trickle-down economics, it seemed, rarely trickled down.

The triumph of the right proved incomplete. The number of government employees actually increased under Reagan. With more than 80% of the federal budget committed to defense, entitlement programs, and interest on the national debt, the right’s goal of deficit elimination floundered for lack of substantial areas to cut. ((Jacobs and Zelizer, 31. )) Between 1980 and 1989 the national debt rose from $914 billion to $2.7 trillion. ((Patterson, Restless Giant, 158.)) Despite steep tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy, the overall tax burden of the American public basically remained unchanged. Moreover, so-called regressive taxes on payroll and certain goods actually increased the tax burden on low- and middle-income Americans. Finally, Reagan slowed but failed to vanquish the five-decade legacy of economic liberalism. Most New Deal and Great Society proved durable. Government still offered its neediest citizens a safety net, if a now continually shrinking one.

Yet the discourse of American politics had irrevocably changed. The preeminence of conservative political ideas grew ever more pronounced, even when as controlled Congress or the White House. Indeed, the Democratic Party adapted its own message in response to the conservative mood of the country that accepted many of the Republicans’ Reagan-era ideas and innovations. The United States was on a rightward path.

Contributors

This chapter was edited by Richard Anderson and William J. Schultz, with content contributions by Richard Anderson, Laila Ballout, Marsha Barrett, Seth Bartee, Eladio Bobadilla, Kyle Burke, Andrew Chadwick, Jennifer Donnally, Leif Fredrickson, Kori Graves, Karissa A. Haugeberg, Jonathan Hunt, Stephen Koeth, Colin Reynolds, William J. Schultz, and Daniel Spillman.

Recommended Reading

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995.

- Crespino, Joseph. In Search of Another Country: Mississippi and the Conservative Counterrevolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Critchlow, Donald. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Dallek, Matthew. The Right Moment: Ronald Reagan’s First Victory and the Decisive Turning Point in American Politics. New York: Free Press, 2000.

- Hunter, James D. Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

- Kruse, Kevin M. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Lassiter, Matthew D. The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Patterson, James T. Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Rodgers, Daniel T. Age of Fracture. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Schoenwald, Jonathan. A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Self, Robert O. All in the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy Since the 1960s. New York: Hill and Wang, 2012.

- Troy, Gil. Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Westad, Odd Arne. The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times. New York: Cambridge University Press, October 2005.

- Wilentz, Sean. The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974–2008. New York: Harper, 2008.

- Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.