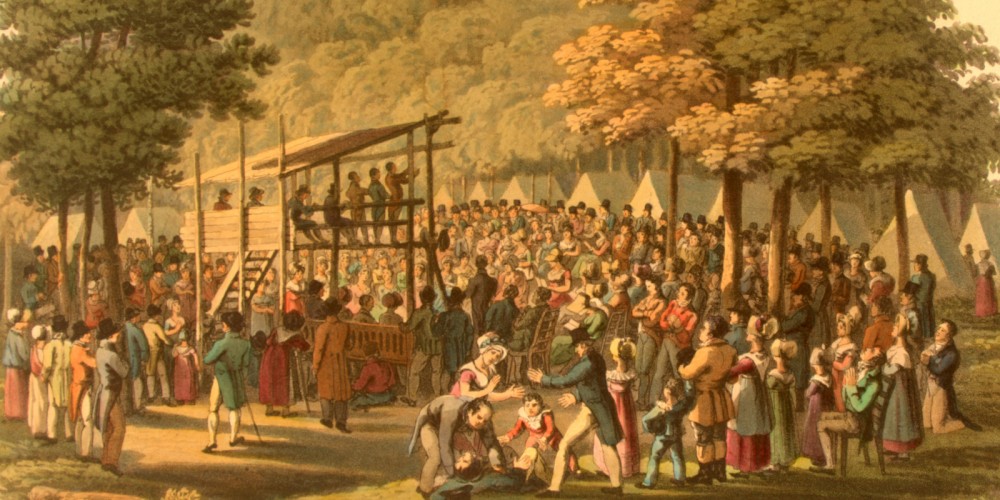

“Camp Meeting of the Methodists in N. America,” 1819, Library of Congress

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

The early nineteenth century was a period of immense change in the United States. Economic, political, demographic, and territorial transformations radically altered how Americans thought about themselves, their communities, and the rapidly expanding nation. It was a period of great optimism, with the possibilities of self-governance infusing everything from religion to politics. Yet it was also a period of great discord, as the benefits of industrialization and democratization increasingly accrued along starkly uneven lines of gender, race, and class. Westward expansion distanced urban dwellers from frontier settlers more than ever before, even as the technological innovations of industrialization—like the telegraph and railroads—offered exciting new ways to maintain communication. The spread of democracy opened the franchise to nearly all white men, but urbanization and a dramatic influx of European migration increased social tensions and class divides.

Americans looked on these changes with a mixture of enthusiasm and suspicion, wondering how the moral fabric of the new nation would hold up to emerging social challenges. Increasingly, many turned to two powerful tools to help understand and manage the various transformations: spiritual revivalism and social reform. Reacting to the rationalism of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, the religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening reignited Protestant spirituality during the early nineteenth century. The revivals incorporated worshippers into an expansive religious community that crisscrossed all regions of the United States and armed them with a potent evangelical mission. Many emerged from these religious revivals with a conviction that human society could be changed to look more heavenly. They joined their spiritual networks to rapidly developing social reform networks that sought to alleviate social ills and eradicate moral vice. Tackling numerous issues, including alcoholism, slavery, and the inequality of women, reformers worked tirelessly to remake the world around them. While not all these initiatives were successful, the zeal of reform and the spiritual rejuvenation that inspired it were key facets of antebellum life and society.

II. Revival and Religious Change

In the early nineteenth century, a succession of religious revivals collectively known as the Second Great Awakening remade the nation’s religious landscape. Revivalist preachers traveled on horseback, sharing the message of spiritual and moral renewal to as many as possible. Residents of urban centers, rural farmlands, and frontier territories alike flocked to religious revivals and camp meetings, where intense physical and emotional enthusiasm accompanied evangelical conversion.

The Second Great Awakening emerged in response to powerful intellectual and social currents. Camp meetings captured the democratizing spirit of the American Revolution, but revivals also provided a unifying moral order and new sense of spiritual community for Americans struggling with the great changes of the day. The market revolution, western expansion, and European immigration all challenged traditional bonds of authority, and evangelicalism promised equal measures of excitement and order. Revivals spread like wildfire throughout the United States, swelling church membership, spawning new Christian denominations, and inspiring social reform.

One of the earliest and largest revivals of the Second Great Awakening occurred in Cane Ridge, Kentucky over a one-week period in August 1801. The Cane Ridge Revival drew thousands of people, and possibly as many as one of every ten residents of Kentucky. Though large crowds had previously gathered annually in rural areas each late summer or fall to receive Communion, this assembly was very different. Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian preachers all delivered passionate sermons, exhorting the crowds to strive for their own salvation. They preached from inside buildings, evangelized outdoors under the open sky, and even used tree stumps as makeshift pulpits, all to reach their enthusiastic audiences in any way possible. Women, too, exhorted, in a striking break with common practice. Attendees, moved by the preachers’ fervor, responded by crying, jumping, speaking in tongues, or even fainting.

Events like the Cane Ridge Revival did spark significant changes in Americans’ religious affiliations. Many revivalists abandoned the comparatively formal style of worship observed in the well-established Congregationalist and Episcopalian churches, and instead embraced more impassioned forms of worship that included the spontaneous jumping, shouting, and gesturing found in new and alternative denominations. The ranks of Christian denominations such as the Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians swelled precipitously alongside new denominations such as the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. The evangelical fire reached such heights, in fact, that one swath of western and central New York state came to be known as the “Burned-Over District.” Charles Grandison Finney, the influential revivalist preacher who first coined the term, explained that the residents of this area had experienced so many revivals by different religious groups that that there were no more souls to awaken to the fire of spiritual conversion.

Within the “spiritual marketplace” created by religious disestablishment, Methodism achieved the most remarkable success. Methodism experienced the most significant denominational increase in American history and was by far the most popular American denomination by 1850. The Methodist denomination grew from fewer than one thousand members at the end of the eighteenth century to constitute thirty-four percent of all American church membership by the mid-nineteenth century. ((John H. Wigger, Taking Heaven by Storm: Methodism and the Rise of Popular Christianity in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 3, 197-200, 201n1.)) After its leaders broke with the Church of England to form a new, American denomination in 1784, the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) achieved its growth through innovation. Methodists used itinerant preachers, known as circuit riders. These men (and the occasional woman) won converts by pushing west with the expanding United States over the Alleghenies and into the Ohio River Valley, bringing religion to new settlers hungry to have their spiritual needs attended. Circuit riding took preachers into homes, meetinghouses, and churches, all mapped out at regular intervals that collectively took about two weeks to complete.

Revolutionary ideals also informed a substantial theological critique of orthodox Calvinism that had far-reaching consequences for religious individuals and for society as a whole. Calvinism began to seem too pessimistic for many American Christians. Worshippers increasingly began to take responsibility for their own spiritual fates by embracing theologies that emphasized human action in effecting salvation, and revivalist preachers were quick to recognize the importance of these cultural shifts. Radical revivalist preachers, such as Charles Grandison Finney, put theological issues aside and evangelized by appealing to worshippers’ hearts and emotions. Even more conservative spiritual leaders, such as Lyman Beecher of the Congregational church, appealed to younger generations of Americans by adopting a less orthodox approach to Calvinist doctrine. Though these men did not see eye to eye, they both contributed to the emerging consensus that all souls are equal in salvation and that all people can be saved by surrendering to God. This idea of spiritual egalitarianism was one of the most important transformations to emerge out of the Second Great Awakening.

Spiritual egalitarianism dovetailed neatly with an increasingly democratic United States. In the process of winning independence from Britain, the Revolution weakened the power of long-standing social hierarchies and the codes of conduct that went along with them. From the institutional side, its democratizing ethos opened the door for a more egalitarian approach to spiritual leadership. Whereas preachers of longstanding denominations like the Congregationalists were required to have a divinity degree and at least some theological training in order to become spiritual leaders, many alternative denominations only required a conversion experience and a supernatural “call to preach.” This meant, for example, that a twenty-year-old man could go from working in a mill to being a full-time circuit-riding preacher for the Methodists practically overnight. Indeed, it was their emphasis on spiritual egalitarianism over formal training that enabled Methodists to outpace spiritual competition during this period. Methodists attracted more new preachers to send into the field, and the lack of formal training meant that individual preachers could be paid significantly less than a Congregationalist preacher with a divinity degree.

In addition to the divisions between evangelical and non-evangelical denominations wrought by the Second Great Awakening, the revivals and subsequent evangelical growth also revealed strains within the Methodist and Baptist churches. Each witnessed several schisms during the 1820s and 1830s as reformers advocated for a return to the practices and policies of an earlier generation, which they charges that church leaders had compromised. Many others left mainstream Protestantism altogether, opting instead to form their own churches. Some, like Alexander Campbell and Barton Stone, proposed a return to (or “restoration” of) New Testament Christianity, stripped of centuries of additional teachings and practices. Other restorationists built on the foundation laid by the evangelical churches by using their methods and means to both critique the Protestant mainstream and move beyond the accepted boundaries of contemporary Christian orthodoxy. Self-declared prophets claimed that God had called them to establish new churches and introduce new (or, in their understanding, restore lost) teachings, forms of worship, and even scripture.

Mormon founder Joseph Smith, for example, claimed that God the Father and Jesus Christ appeared to him in a vision in a grove of trees near his boyhood home in upstate New York and commanded him to “join none of [the existing churches], for they are all wrong.” ((Joseph Smith, “History, 1838-1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805-30 August 1834,” The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed 8 July 2015, http://josephsmithpapers.org/paperSummary/history-1838-1856-volume-a-1-23-december-1805-30-august-1834.)) Subsequent visitations from angelic beings revealed to Smith the location of a buried record, purportedly containing the writings and histories of an ancient Christian civilization on the American continent. Smith published the Book of Mormon in early 1830, and organized the Church of Christ (later renamed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) a short time later. Borrowing from the Methodists a faith in the abilities of itinerant preachers without formal training, Smith dispatched early converts as missionaries to take the message of the Book of Mormon throughout the United States, across the ocean to England and Ireland, and eventually even further abroad. He attracted a sizeable number of followers on both sides of the Atlantic and commanded them to gather to a center place, where they collectively anticipated the imminent second coming of Christ. Continued growth and near-constant opposition from both Protestant ministers and neighbors suspicious of their potential political power forced the Mormons to move several times, first from New York to Ohio, then to Missouri, and finally to Illinois, where they established a thriving community on the banks of the Mississippi River. In Nauvoo, as they called their city, Smith moved even further beyond the bounds of the Christian orthodoxy by continuing to pronounce additional revelations and introducing secret rites to be performed in Mormon temples. Most controversially, Smith and a select group of his most loyal followers began taking additional wives (Smith himself married at least 30 other women). Although Mormon polygamy was not publicly acknowledged and openly practiced until 1852 (when the Mormons had moved yet again, this time to the protective confines of the intermountain west on the shores of the Great Salt Lake), rumors of Smith’s involvement circulated almost immediately after its quiet introduction, and played a part in the motivations of the mob that eventually murdered the Mormon prophet in the summer of 1844.

Mormons were not the only religious community in antebellum America to challenge the domestic norms of the era through radical sexual experiments: Shakers strictly enforced celibacy in their several communes scattered throughout New England and the upper Midwest, while John Humphrey Noyes introduced free love (or “complex marriage”) to his Oneida community in upstate New York. Others challenged existing cultural customs in less radical ways. For individual worshippers, spiritual egalitarianism in revivals and camp meetings could break down traditional social conventions. For example, revivals generally admitted both men and women. Furthermore, in an era when many American Protestants discouraged or outright forbade women from speaking in church meetings, some preachers provided women with new opportunities to openly express themselves and participate in spiritual communities. This was particularly true in the Methodist and Baptist traditions, though by the mid-nineteenth century most of these opportunities would be curtailed as these denominations attempted to move away from radical revivalism and towards the status of respectable denominations. Some preachers also promoted racial integration in religious gatherings, expressing equal concern for white and black people’s spiritual salvation and encouraging both slaveholders and the enslaved to attend the same meetings. Historians have even suggested that the extreme physical and vocal manifestations of conversion seen at impassioned revivals and camp meetings offered the ranks of worshippers a way to enact a sort of social leveling by flouting the codes of self-restraint prescribed by upper-class elites. Although the revivals did not always live up to such progressive ideals in practice, particularly in the more conservative regions of the slaveholding South, the concept of spiritual egalitarianism nonetheless challenged and changed the ways that Protestant Americans thought about themselves, their God, and one another.

As the borders of the United States expanded during the nineteenth century and as new demographic changes altered urban landscapes, revivalism also offered worshippers a source of social and religious structure to help cope with change. Revival meetings held by itinerant preachers offered community and collective spiritual purpose to migrant families and communities isolated from established social and religious institutions. In urban centers, where industrialization and European famines brought growing numbers of domestic and foreign migrants, evangelical preachers provided moral order and spiritual solace to an increasingly anonymous population. Additionally, and quite significantly, the Second Great Awakening armed evangelical Christians with a moral purpose to address and eradicate the many social problems they saw as arising from these dramatic demographic shifts.

Not all American Christians, though, were taken with the revivals. The early nineteenth century also saw the rise of Unitarianism as a group of ministers and their followers came to reject key aspects of “orthodox” Protestant belief including the divinity of Christ. Christians in New England were particularly involved in the debates surrounding Unitarianism as Harvard University became a hotly contested center of cultural authority between Unitarians and Trinitarians. Unitarianism had important effects on the world of reform when a group of Unitarian ministers founded the Transcendental Club in 1836. The club met for four years and included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Frederic Henry Hedge, George Ripley, Orestes Brownson, James Freeman Clarke, and Theodore Parker. While initially limited to ministers or former ministers—except for the eccentric Alcott—the club quickly expanded to include numerous literary intellectuals. Among these were the author Henry David Thoreau, the proto-feminist and literary critic Margaret Fuller, and the educational reformer Elizabeth Peabody.

Transcendentalism had no established creed, but this was intentional. What united the Transcendentalists was their belief in a higher spiritual principle within each person that could be trusted to discover truth, guide moral action, and inspire art. They often referred to this principle as “Soul,” “Spirit,” “Mind,” or “Reason.” Deeply influenced by British Romanticism and German idealism’s celebration of individual artistic inspiration, personal spiritual experience, and aspects of human existence not easily explained by reason or logic, the Transcendentalists established an enduring legacy precisely because they developed distinctly American ideas that emphasized individualism, optimism, oneness with nature, and a modern orientation toward the future rather than the past. These themes resonated in an American nineteenth century where political democracy and readily available land distinguished the United States from Europe.

Ralph Waldo Emerson espoused a religious worldview wherein God, “the eternal ONE,” manifested through the special harmony between the individual soul and nature. In “The American Scholar” (1837) and “Self-Reliance” (1841), Emerson emphasized the utter reliability and sufficiency of the individual soul, and exhorted his audience to overcome “our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands.” ((Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar” http://digitalemerson.wsulibs.wsu.edu/exhibits/show/text/the-american-scholar; Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self Reliance” in Essays, First Series http://digitalemerson.wsulibs.wsu.edu/exhibits/show/text/first-series/self-reliance.)) Emerson believed that the time had come for Americans to declare their intellectual independence from Europe. Henry David Thoreau espoused a similar enthusiasm for simple living, communion with nature, and self-sufficiency. Thoreau’s sense of rugged individualism, perhaps the strongest among even the Transcendentalists, also yielded “Resistance to Civil Government” (1849). ((Henry David Thoreau, Walden and On the Duty of Civil Disobedience, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/205/205-h/205-h.htm)) Several of the Transcendentalists also participated in communal living experiments. For example, in the mid-1840s, George Ripley and other members of the utopian Brook Farm community began to espouse Fourierism, a vision of society based upon cooperative principles, as an alternative to capitalist conditions.

Many of these different types of response to the religious turmoil of the time had a similar endpoint in the embrace of voluntary associations and social reform work. During the antebellum period, many American Christians responded to the moral anxiety of industrialization and urbanization by organizing to address specific social needs. Social problems such as intemperance, vice, and crime assumed a new and distressing scale that older solutions, such as almshouses, were not equipped to handle. Moralists grew concerned about the growing mass of urban residents who did not attend church, and who, thanks to poverty or illiteracy, did not even have access to Scripture. Voluntary benevolent societies exploded in number to tackle these issues. Led by ministers and dominated by middle-class women, voluntary societies printed and distributed Protestant tracts, taught Sunday school, distributed outdoor relief, and evangelized in both frontier towns and urban slums. These associations and their evangelical members also lent moral backing and manpower to large-scale social reform projects, including the temperance movement designed to curb Americans’ consumption of alcohol, the abolitionist campaign to eradicate slavery in the United States, and women’s rights agitation to improve women’s political and economic rights. As such wide-ranging reform projects combined with missionary zeal, evangelical Christians formed a “benevolent empire” that swiftly became a cornerstone of the antebellum period.

III. Atlantic Origins of Reform

The reform movements that emerged in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century were not American inventions. Instead, these movements were rooted in a transatlantic world where both sides of the ocean faced similar problems and together collaborated to find similar solutions. Many of the same factors that spurred American reformers to action—such as urbanization, industrialization, and class struggle—equally affected Europe. Reformers on both sides of the Atlantic visited and corresponded with one another, exchanging ideas and building networks that proved crucial to shared causes like abolition and women’s rights.

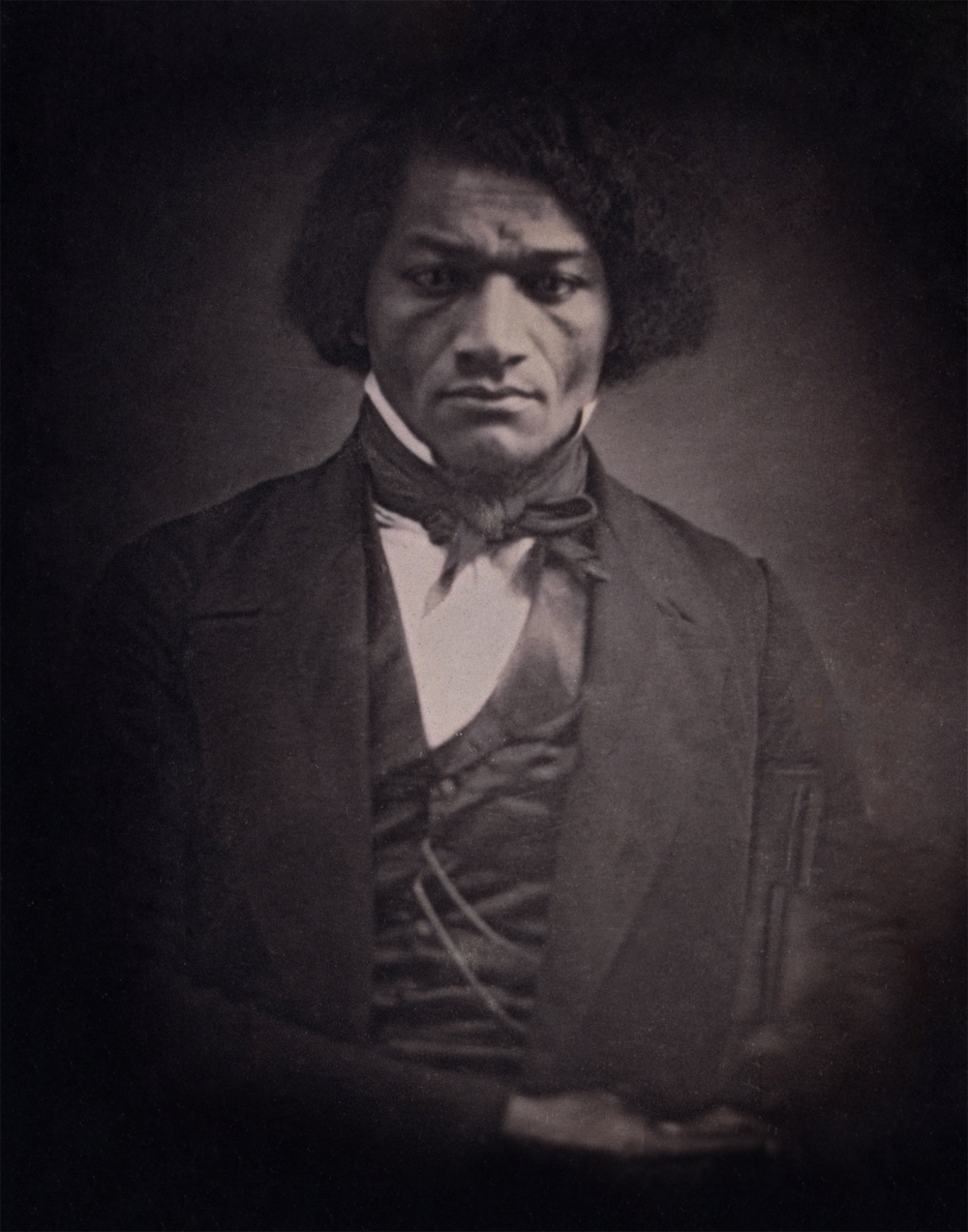

Deepening ties between reformers across the Atlantic owed not just to the emergence of new ideas, but also to the material connection of the early nineteenth century. Improvements in transportation, including the introduction of the steamboat, canals, and railroads, connected people not just across the United States, but also with other like-minded reformers in Europe. (Ironically, the same technologies also helped ensure that even after the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, the British remained heavily invested in slavery, both directly and indirectly.) Equally important, the reduction of publication costs created by the printing technologies of the 1830s allowed reformers to reach new audiences across the world. Almost immediately after its publication in the United States, for instance, the escaped slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass’s autobiography was republished in Europe and translated into French and Dutch, galvanizing Douglass’s supporters across the Atlantic. ((Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself (Boston: Published at the Anti-Slavery Office, 1845), http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/douglass.html))

Such exchanges began as part of the larger processes of colonialism and empire-building. Missionary organizations from the colonial era had created many of these transatlantic links that were further developed by the Atlantic travel of major figures such as George Whitefield during the First Great Awakening. By the early national period, these networks had changed as a result of the American Revolution but still revealed spiritual and personal connections between religious individuals and organizations in the United States and Great Britain, in particular. These connections can be seen in multiple areas. Mission work continued to be a joint effort, with American and European missionary societies in close correspondence throughout the early nineteenth century as they coordinated domestic and foreign evangelistic missions. The transportation and print revolutions meant that news of British missionary efforts in India and Tahiti could be quickly printed in American religious periodicals, galvanizing American efforts to evangelize among Native Americans, frontier settlers, immigrant groups, and even overseas.

In addition to missions, anti-slavery work had a decidedly transatlantic cast from its very beginnings. American Quakers began to question slavery as early as the late-17th century, and worked with British reformers in the successful campaign that ended the slave trade, and then slavery itself, in the early nineteenth century. Before, during, and after the Revolution, many Americans continued to admire European thinkers. Influence extended both east and west. By foregrounding questions about rights, the American Revolution helped inspire British abolitionists, who in turn offered support to their American counterparts. American antislavery activists developed close relationships with British abolitionists such as Thomas Clarkson, Daniel O’Connell, and Joseph Sturge. Prominent American abolitionists such as Theodore Dwight Weld, Lucretia Mott, and William Lloyd Garrison were converted to the antislavery idea of immediatism—that is, the demand for emancipation without delay—by British abolitionists Elizabeth Heyrick and Charles Stuart. Although Anglo-American antislavery networks reached back to the late-eighteenth century, they dramatically grew in support and strength over the antebellum period, as evidenced by the General Antislavery Convention of 1840. This antislavery delegation consisted of more than 500 abolitionists, mostly coming from France, England, and the United States. All met together in England, united by their common goal of ending slavery in their time. Although abolitionism was not the largest American reform movement of the antebellum period (that honor belongs to temperance), it did foster greater cooperation among reformers in England and the United States.

This enormous painting documents the 1840 convention of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, established by both American and English anti-slavery activists to promote worldwide abolition. Benjamin Haydon, The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840. Wikimedia.

In the course of their abolitionist activities, many American women began to establish contact with their counterparts across the Atlantic, each group penning articles and contributing material support to the others’ antislavery publications and fundraisers. The effect of this cooperation can be seen in the nascent women’s rights movement. During the 1840 London meeting, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formulated the idea for a national women’s suffrage convention, which they held at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. The General Antislavery Convention played an important role in laying the foundation for an Anglo-American Women’s Suffrage Movement. In her history of the woman suffrage movement, Stanton would mark the Convention as the beginning of that movement. ((Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, The History of Woman Suffrage, 2nd Edition (Rochester, NY: Charles Mann, 1889) http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28020/28020-h/28020-h.htm.))

The bonds between British and American reformers can be traced throughout the many social improvement projects of the nineteenth century. Transatlantic cooperation galvanized efforts to reform individuals’ and societies’ relationships to alcohol, labor, religion, education, commerce, and land ownership. This cooperation, stemming from the recognition that social problems on both sides of the Atlantic were strikingly similar, helped American reformers to conceptualize themselves as part of a worldwide moral mission to attack social ills and spread the gospel of Christianity.

IV. The Benevolent Empire

After religious disestablishment, citizens of the United States faced a dilemma: how to cultivate a moral and virtuous public without aid from state-sponsored religion. Most Americans agreed that a good and moral citizenry was essential for the national project to succeed, but many shared the perception that society’s moral foundation was weakening. Narratives of moral and social decline, known as jeremiads, had long been embedded in Protestant story-telling traditions, but jeremiads took on new urgency in the antebellum period. In the years immediately following disestablishment, “traditional” Protestant Christianity was at low tide, while the Industrial Revolution and the spread of capitalism had led to a host of social problems associated with cities and commerce. The Second Great Awakening was in part a spiritual response to such changes, revitalizing Christian spirits through the promise of salvation. The revivals also provided an institutional antidote to the insecurities of a rapidly changing world by inspiring an immense and widespread movement for social reform. Growing directly out of nineteenth-century revivalism, networks of reform societies proliferated throughout the United States between 1815 and 1861, melding religion and reform into a powerful force in American culture known as the “benevolent empire.”

The benevolent empire departed from revivalism’s early populism, as middle class ministers dominated the leadership of antebellum reform societies. Due to the economic forces of the market revolution, it was the middle-class evangelicals who had the time and resources to devote to reforming efforts. Often, that reform focused on creating and maintaining respectable middle-class culture throughout the United States. Middle-class women, in particular, were able to play a leading role in reform activity. They became increasingly responsible for the moral maintenance of their homes and communities, and their leadership signaled a dramatic departure from previous generations when such prominent roles for ordinary women would have been unthinkable.

Different forces within evangelical Protestantism combined to encourage reform. One of the great lights of benevolent reform was Charles Grandison Finney, the radical revivalist, who promoted a movement known as “perfectionism.” Premised on the belief that truly redeemed Christians would be motivated to live free of sin and reflect the perfection of God himself, his wildly popular revivals encouraged his converted followers to join reform movements and create God’s kingdom on earth. The idea of “disinterested benevolence” also turned many evangelicals toward reform. Preachers championing disinterested benevolence argued that true Christianity requires that a person give up self-love in favor of loving others. Though perfectionism and disinterested benevolence were the most prominent forces encouraging benevolent societies, some preachers achieved the same end in their advocacy of postmillennialism. In this worldview, Christ’s return was foretold to occur after humanity had enjoyed one thousand years’ peace, and it was the duty of converted Christians to improve the world around them in order to pave the way for Christ’s redeeming return. Though ideological and theological issues like these divided Protestants into more and more sects, church leaders often worked on an interdenominational basis to establish benevolent societies and draw their followers into the work of social reform.

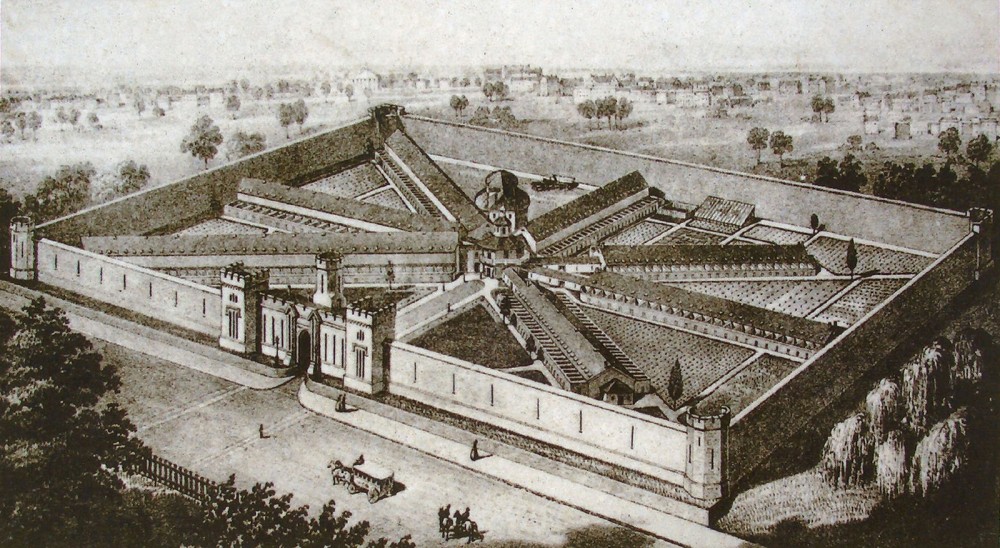

Under the leadership of preachers and ministers, reform societies attacked many social problems. Those concerned about drinking could join temperance societies; other groups focused on eradicating dueling and gambling. Evangelical reformers might support home or foreign missions or Bible and tract societies. Sabbatarians fought tirelessly to end non-religious activity on the Sabbath. Moral reform societies sought to end prostitution and redeem “fallen women.” Over the course of the antebellum period, voluntary associations and benevolent activists also worked to reform bankruptcy laws, prison systems, insane asylums, labor laws, and education. They built orphanages and free medical dispensaries, and developed programs to provide professional services like social work, job placement, and day camps for children in the slums.

Eastern State Penitentiary changed the principles of imprisonment, focusing on reform rather than punishment. The structure itself used the panopticon surveillance system, and was widely copied by prison systems around the world. P.S: Duval and Co., The State Penitentiary for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 1855. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eastern_State_Penitentiary_aerial_crop.jpg.

Frequently, these organizations shared membership as individuals found themselves interested in a wide range of reform movements. This overlapping membership contributed to the sense of the groups as forming an empire of benevolence, particularly during Anniversary Week, when many of the major reform groups coordinated the schedules of their annual meetings in New York or Boston to allow individuals to attend multiple meetings in a single trip.

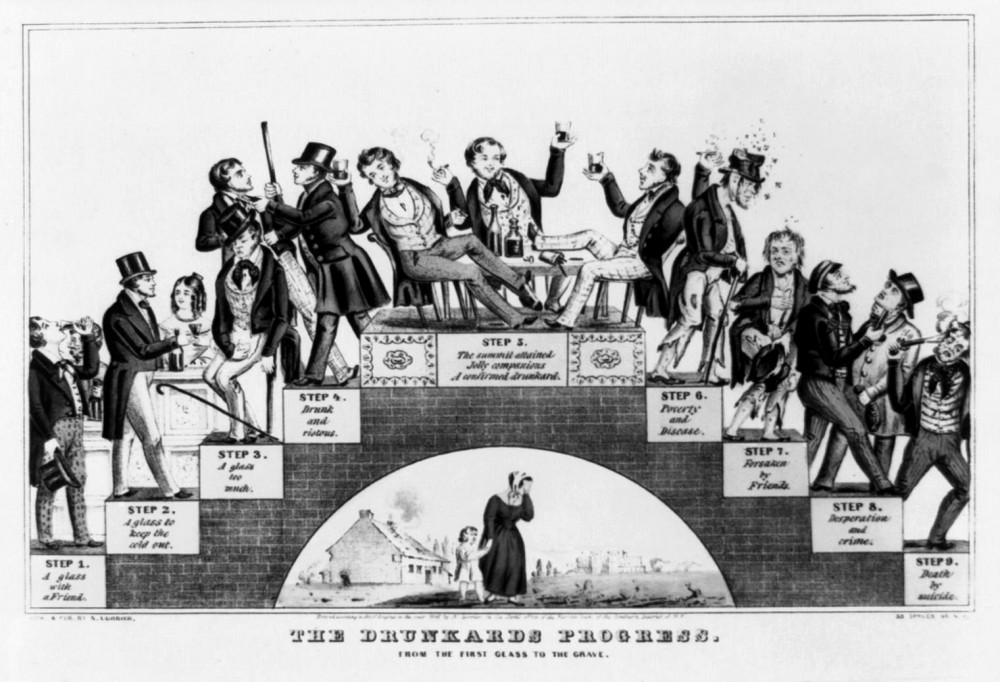

Among all the social reform movements associated with the benevolent empire, the temperance crusade was the most successful. Championed by prominent preachers like Lyman Beecher, the movement’s effort to curb the consumption of alcohol galvanized widespread support among the middle class. Alcohol consumption became a significant social issue after the American Revolution. Commercial distilleries produced readily available, cheap whiskey that was frequently more affordable than milk or beer and safer than water, and hard liquor became a staple beverage in many lower- and middle-class households. Consumption among adults skyrocketed in the early nineteenth century, and alcoholism had become an endemic problem across the United States by the 1820s. As alcoholism became an increasingly visible issue in towns and cities, most reformers escalated their efforts from advocating moderation in liquor consumption to full abstinence from all alcohol.

Many reformers saw intemperance as the biggest impediment to maintaining order and morality in the young republic. Temperance reformers saw a direct correlation between alcohol and other forms of vice targeted by voluntary societies, and, most importantly, felt that it endangered family life. In 1826, evangelical ministers organized the American Temperance Society to help spread the crusade more effectively on a national level. It supported lecture campaigns, produced temperance literature, and organized revivals specifically aimed at encouraging worshippers to give up the drink. It was so successful that, within a decade, it established five thousand branches and grew to over a million members. ((Milton A. Maxwell, “Washingtonian Movement,” Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Vol. 11 (1950), 410.)) Temperance reformers pledged not to touch the bottle, and canvassed their neighborhoods and towns to encourage others to join their “Cold Water Army.” They also targeted the law, successfully influencing lawmakers in several states to prohibit the sale of liquor.

In response to the perception that heavy drinking was associated with men who abused, abandoned, or neglected their family obligations, women formed a significant presence in societies dedicated to eradicating liquor. Temperance became a hallmark of middle-class respectability among both men and women and developed into a crusade with a visible class character. As with many of the reform efforts championed by the middle class, temperance threatened to intrude on the private family life of lower-class workers, many of whom were Irish Catholics. Such intrusions by the Protestant middle-class exacerbated class, ethnic, and religious tensions. Still, while the temperance movement made less substantial inroads into lower-class workers’ heavy-drinking social culture, the movement was still a great success for the reformers. In the 1830s, Americans drank half of what they had in the 1820s, and per capita consumption continued to decline over the next two decades. ((Jack S. Blocker, American Temperance Movements: Cycles of Reform (Boston: 1989).)).

Though middle-class reformers worked tirelessly to cure all manner of social problems through institutional salvation and voluntary benevolent work, they regularly participated in religious organizations founded explicitly to address the spiritual mission at the core of evangelical Protestantism. In fact, for many reformers, it was actually the experience of evangelizing among the poor and seeing firsthand the rampant social issues plaguing life in the slums that first inspired them to get involved in benevolent reform projects. Modeling themselves on the British and Foreign Bible Society, formed in 1804 to spread Christian doctrine to the British working class, urban missionaries emphasized the importance of winning the world for Christ, one soul at a time. For example, the American Bible Society and the American Tract Society used the efficient new steam-powered printing press to distribute bibles and evangelizing religious tracts throughout the United States. For example, the New York Religious Tract Society alone managed to distribute religious tracts to all but 388 of New York City’s 28,383 families. ((David Paul Nord, Faith in Reading: Religious Publishing and the Birth of Mass Media in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 222), 85.)) In places like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, middle-class women also established groups specifically to canvass neighborhoods and bring the gospel to lower-class “wards.”

Such evangelical missions extended well beyond the urban landscape, however. Stirred by nationalism and moral purpose, evangelicals labored to make sure the word of God reached far-flung settlers on the new American frontier. The American Bible Society distributed thousands of Bibles to frontier areas where churches and clergy were scarce, while the American Home Missionary Society provided substantial financial assistance to frontier congregations struggling to achieve self-sufficiency. Missionaries worked to translate the Bible into Iroquois and other languages in order to more effectively evangelize Native American populations. As efficient printing technology and faster transportation facilitated new transatlantic and global connections, religious Americans also began to flex their missionary zeal on a global stage. In 1810, for example, Presbyterian and Congregationalist leaders established the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to evangelize in India, Africa, East Asia, and the Pacific.

The potent combination of social reform and evangelical mission at the heart of the nineteenth century’s benevolent empire produced reform agendas and institutional changes that have reverberated through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. By devoting their time to the moral uplift of their communities and the world at large, middle-class reformers created many of the largest and most influential organizations in the nation’s history. For the optimistic, religiously motivated American, no problem seemed too great to solve.

Difficulties could arise, however, when the benevolent empire attempted to take up more explicitly political issues. The movement against Indian removal was the first major example of this. Missionary work had first brought the Cherokee Nation to the attention of Northeastern evangelicals in the early nineteenth century. Missionaries sent by the American Board and other groups sought to introduce Christianity and American cultural values to the Cherokee, and celebrated when their efforts seemed to be met with success. Evangelicals proclaimed that the Cherokee were becoming “civilized,” which could be seen in their adoption of a written language and of a constitution modeled on the U.S. government. Mission supporters were shocked, then, when the election of Andrew Jackson brought a new emphasis on the removal of Native Americans from the land east of the Mississippi River. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was met with fierce opposition from within the affected Native American communities as well as from the benevolent empire. Jeremiah Evarts, one of the leaders of the American Board, wrote a series of essays under the pen name of William Penn urging Americans to oppose removal. ((Jeremiah Evarts, Essays on the Present Crisis in the Condition of the American Indians: First Published in the National Intelligencer, under the signature of William Penn (Boston: Perkins and Marvin, 1829) http://eco.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.51209/3?r=0&s=1.)) He used the religious and moral arguments of the mission movement, but added a new layer of politics in his extensive discussion of the history of treaty law between the United States and Native Americans. This political shift was even more evident when American missionaries challenged Georgia state laws asserting sovereignty over Cherokee territory in the Supreme Court Case Worcester v. Georgia. ((Worcester v. Georgia (1832) https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/31/515.)) Although successful in Court, the federal government did not enforce the Court’s decision and the opposition to Indian Removal was ultimately defeated with the Trail of Tears. It marked an important transition in the history of American religion and reform with this introduction of national politics.

Anti-removal activism was also notable for the entry of ordinary American women into political discourse. The first major petition campaign by American women focused on opposition to removal and was led (anonymously) by Catharine Beecher. Beecher was already a leader in the movement to reform women’s education and came to her role in removal through her connections to the mission movement. Inspired by a meeting with Jeremiah Evarts, Beecher echoed his arguments from the William Penn letters in her appeal to American women. ((Catharine Beecher, “Circular Addressed to the Benevolent Ladies of the U. States,” Dec. 25, 1829, in Theda Purdue and Michael D. Green, eds., The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents, 2nd ed. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2005), 111-14. Available online through Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000.)) Using religious and moral arguments to justify women’s entry into political discussion when it concerned an obviously moral cause, Beecher called on women to petition the government to end the policy of Indian removal. This effort was ultimately unsuccessful, but was significant for its introduction of the kinds of arguments that would pave the way for women’s political activism for abolitionism and women’s rights. The divisions that the anti-removal campaign revealed would only become more dramatic with the next political cause of nineteenth century reformers: abolitionism.

V. Antislavery and Abolitionism

The revivalist doctrines of salvation, perfectionism, and disinterested benevolence led many evangelical reformers to believe that slavery was the most God-defying of all sins and the most terrible blight on the moral virtue of the United States. While white interest in and commitment to abolition had existed for several decades, organized antislavery advocacy had been largely restricted to models of gradual emancipation (seen in several northern states following the American Revolution) and conditional emancipation (seen in colonization efforts to remove black Americans to settlements in Africa). The colonizationist movement of the early nineteenth century had drawn together a broad political spectrum of Americans with its promise of gradually ending slavery in the United States by removing the free black population from North America. By the 1830s, however, a rising tide of anti-colonization sentiment among northern free blacks and middle-class evangelicals’ flourishing commitment to social reform radicalized the movement. Baptists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Congregational revivalists like Arthur and Lewis Tappan and Theodore Dwight Weld, and radical Quakers including Lucretia Mott and John Greenleaf Whittier helped push the idea of immediate emancipation onto the center stage of northern reform agendas. Inspired by a strategy known as “moral suasion,” these young abolitionists believed they could convince slaveholders to voluntarily release their slaves by appealing to their sense of Christian conscience. The result would be national redemption and moral harmony.

William Loyd Garrison’s early life and career famously illustrated this transition toward immediatism among radical Christian reformers. As a young man immersed in the reform culture of antebellum Massachusetts, Garrison had fought slavery in the 1820s by advocating for both black colonization and gradual abolition. Fiery tracts penned by black northerners David Walker and James Forten, however, convinced Garrison that colonization was an inherently racist project and that African Americans possessed a hard-won right to the fruits of American liberty. So, in 1831, he established a newspaper called The Liberator, through which he organized and spearheaded an unprecedented interracial crusade dedicated to promoting immediate emancipation and black citizenship. Then, in 1833, Garrison presided as reformers from ten states came together to create the American Antislavery Society. They rested their mission for immediate emancipation “upon the Declaration of our Independence, and upon the truths of Divine Revelation,” binding their cause to both national and Christian redemption. Abolitionists fought to save slaves and their nation’s soul.

In order to accomplish their goals, abolitionists employed every method of outreach and agitation used in the social reform projects of the benevolent empire. At home in the North, abolitionists established hundreds of antislavery societies and worked with long-standing associations of black activists to establish schools, churches, and voluntary associations. Women and men of all colors were encouraged to associate together in these spaces to combat what they termed “color phobia.” Harnessing the potential of steam-powered printing and mass communication, abolitionists also blanketed the free states with pamphlets and antislavery newspapers. They blared their arguments from lyceum podiums and broadsides. Prominent individuals such as Wendell Phillips and Angelina Grimké saturated northern media with shame-inducing exposés of northern complicity in the return of fugitive slaves, and white reformers sentimentalized slave narratives that tugged at middle-class heartstrings. Abolitionists used the United States Postal Service in 1835 to inundate southern slaveholders’ with calls to emancipate their slaves in order to save their souls, and, in 1836, they prepared thousands of petitions for Congress as part of the “Great Petition Campaign.” In the six years from 1831 to 1837, abolitionist activities reached dizzying heights.

However, such efforts encountered fierce opposition, as most Americans did not share abolitionists’ particular brand of nationalism. In fact, abolitionists remained a small, marginalized group detested by most white Americans in both the North and the South. Immediatists were attacked as the harbingers of disunion, rabble-rousers who would stir up sectional tensions and thereby imperil the American experiment of self-government. Particularly troubling to some observers was the public engagement of women as abolitionist speakers and activists. Fearful of disunion and outraged by the interracial nature of abolitionism, northern mobs smashed abolitionist printing presses and even killed a prominent antislavery newspaper editor named Elijah Lovejoy. White southerners, believing that abolitionists had incited Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831, aggressively purged antislavery dissent from the region. Violent harassment threatened abolitionists’ personal safety. In Congress, Whigs and Democrats joined forces in 1836 to pass an unprecedented restriction on freedom of political expression known as the “gag rule,” prohibiting all discussion of abolitionist petitions in the House of Representatives. Two years later, mobs attacked the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, throwing rocks through the windows and burning the newly constructed Pennsylvania Hall to the ground.

In the face of such substantial external opposition, the abolitionist movement began to splinter. In 1839, an ideological schism shook the foundations of organized antislavery. Moral suasionists, led most prominently by William Lloyd Garrison, felt that the United States Constitution was a fundamentally pro-slavery document, and that the present political system was irredeemable. They dedicated their efforts exclusively towards persuading the public to redeem the nation by re-establishing it on antislavery grounds. However, many abolitionists, reeling from the level of entrenched opposition met in the 1830s, began to feel that moral suasion was no longer realistic. Instead, they believed, abolition would have to be effected through existing political processes. So, in 1839, political abolitionists formed the Liberty Party under the leadership of James G. Birney. This new abolitionist society was predicated on the belief that the U.S. Constitution was actually an antislavery document that could be used to abolish the stain of slavery through the national political system.

Women’s rights, too, divided abolitionists. Many abolitionists who believed full-heartedly in moral suasion nonetheless felt compelled to leave the American Antislavery Association because, in part, it elevated women to leadership positions and endorsed women’s suffrage. This question came to a head when, in 1840, Abby Kelly was elected to the business committee of the American Antislavery Society. The elevation of women to full leadership roles was too much for some conservative members who saw this as evidence that, in an effort to achieve general perfectionism, the American Antislavery Society had lost sight of its most important goal. Under the leadership of Arthur Tappan, they left to form the American and Foreign Antislavery Society. Though these disputes were ultimately mere road bumps on the long path to abolition, they did become so bitter and acrimonious that former friends cut social ties and traded public insults.

Another significant shift stemmed from the disappointments of the 1830s. Abolitionists in the 1840s increasingly moved from agendas based on reform to agendas based on resistance. While moral suasionists continued to appeal to hearts and minds, and political abolitionists launched sustained campaigns to bring abolitionist agendas to the ballot box, the entrenched and violent opposition of slaveholders and the northern public to their reform efforts encouraged abolitionists to focus on other avenues of fighting the slave power. Increasingly, for example, abolitionists focused on helping and protecting runaway slaves, and on establishing international antislavery support networks to help put pressure on the United States to abolish the institution. Frederick Douglass is one prominent example of how these two trends came together. After escaping from slavery, Douglass came to the fore of the abolitionist movement as a naturally gifted orator and a powerful narrator of his experiences in slavery. His first autobiography, published in 1845, was so widely read that it was reprinted in nine editions and translated into several languages. Douglass traveled to Great Britain in 1845, and met with famous British abolitionists like Thomas Clarkson, drumming up moral and financial support from British and Irish antislavery societies. He was neither the first nor the last runaway slave to make this voyage, but his great success abroad contributed significantly to rousing morale among weary abolitionists at home.

Frederick Douglass was perhaps the most famous African American abolitionist, fighting tirelessly not only for the end of slavery but for equal rights of all American citizens. This copy of a daguerreotype shows him as a young man, around the age of 29 and soon after his self-emancipation. Print, c. 1850 after c. 1847 daguerreotype. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Unidentified_Artist_-_Frederick_Douglass_-_Google_Art_Project-restore.png.

The model of resistance to the slave power only became more pronounced after 1850, when a long-standing Fugitive Slave Act was given new teeth. Though a legal mandate to return runway slaves had existed in U.S. federal law since 1793, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 upped the ante by harshly penalizing officials who failed to arrest runaways and private citizens who tried to help them. This law, coupled with growing concern over the possibility that slavery would be allowed in Kansas when it was admitted as a state, made the 1850s a highly volatile and violent period of American antislavery. Reform took a backseat as armed mobs protected runaway slaves in the north and fortified abolitionists engaged in bloody skirmishes in the west. Culminating in John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, the violence of the 1850s convinced many Americans that the issue of slavery was pushing the nation to the brink of sectional cataclysm. After two decades of immediatist agitation, the idealism of revivalist perfectionism had given way to a protracted battle for the moral soul of the country.

For all of the problems that abolitionism faced, the movement was far from a failure. The prominence of African Americans in abolitionist organizations offered a powerful, if imperfect, model of interracial coexistence. While immediatists always remained a minority, their efforts paved the way for the moderately antislavery Republican Party to gain traction in the years preceding the Civil War. It is hard to imagine that Abraham Lincoln could have become president in 1860 without the ground prepared by antislavery advocates and without the presence of radical abolitionists against whom he could be cast as a moderate alternative. Though it ultimately took a civil war to break the bonds of slavery in the United States, the evangelical moral compass of revivalist Protestantism provided motivation for the embattled abolitionists.

VI. Women’s Rights in Antebellum America

In the era of revivalism and reform, Americans understood the family and home as the hearthstones of civic virtue and moral influence. This increasingly confined middle-class white women to the domestic sphere, where they were responsible for educating children and maintaining household virtue. Yet women took the very ideology that defined their place in the home and managed to use it to fashion a public role for themselves. As a result, women actually became more visible and active in the public sphere than ever before. The influence of the Second Great Awakening, coupled with new educational opportunities available to girls and young women, enabled white middle-class women to leave their homes en masse, joining and forming societies dedicated to everything from literary interests to the antislavery movement.

In the early nineteenth century, the dominant understanding of gender claimed that women were the guardians of virtue and the spiritual heads of the home. Women were expected to be pious, pure, submissive, and domestic, and to pass these virtues on to their children. Historians have described these expectations as the “Cult of Domesticity,” or the “Cult of True Womanhood,” and they developed in tandem with industrialization, the market revolution, and the Second Great Awakening. These economic and religious transformations increasingly seemed to divide the world into the public space of work and politics and the domestic space of leisure and morality. Voluntary work related to labor laws, prison reform, and antislavery applied women’s roles as guardians of moral virtue to address all forms of social issues that they felt contributed to the moral decline of society. In spite of this apparent valuation of women’s position in society, there were clear limitations. Under the terms of coverture, men gained legal control over their wives’ property, and women with children had no legal rights over their offspring. Additionally, women could not initiate divorce, make wills, sign contracts, or vote.

Female education provides an example of the great strides made by and for women during the antebellum period. As part of a larger education reform movement in the early republic, several female reformers worked tirelessly to increase women’s access to education. They argued that if women were to take charge of the education of their children, they needed to be well educated themselves. While the women’s education movement did not generally push for women’s political or social equality, it did assert women’s intellectual equality with men, an idea that would eventually have important effects. Educators such as Emma Willard, Catharine Beecher, and Mary Lyons (founders of the Troy Female Seminary, Hartford Female Seminary, and Mount Holyoke Seminary, respectively) adopted the same rigorous curriculum as that used for boys. Many of these schools had the particular goal of training women to be teachers. Many graduates of these prominent seminaries would go on to found their own schools, spreading a more academic women’s education across the country and with it, ideas about women’s potential to take part in public life.

The abolitionist movement was another important school for women’s public engagement. Many of the earliest women’s rights advocates began their activism by fighting the injustices of slavery, including Angelina Grimké, Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. In the 1830s, women in cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia established female societies dedicated to the antislavery mission. Initially, these societies were similar to the prayer and fundraising-based projects of other reform societies. As such societies proliferated, however, their strategies changed. Women could not vote, for example, but they increasingly used their right to petition to express their antislavery grievances to the government. Impassioned women like the Grimké sisters even began to travel on lecture circuits dedicated to the cause. This latter strategy, born out of fervent antislavery advocacy, ultimately tethered the cause of women’s rights to that of abolitionism.

Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Emily Grimké were born to a wealthy family in Charleston, South Carolina, where they witnessed firsthand the horrors of slavery. Repulsed by the treatment of the slaves on the Grimké plantation, they decided to support the antislavery movement by sharing their experiences on Northern lecture tours. At first speaking to female audiences, they soon attracted “promiscuous” crowds of both men and women. They were among the earliest and most famous American women to take such a public role in the name of reform. When the Grimké sisters met substantial harassment and opposition to their public speaking on antislavery, they were inspired to speak out against more than the slave system. They began to see that they would need to fight for women’s rights simply in order to be able to fight for the rights of slaves. Other female abolitionists soon joined them in linking the issues of women’s rights and abolitionism by drawing direct comparisons between the condition of free women in the United States and the condition of the slave.

As the antislavery movement gained momentum in the northern states in the 1830s and 1840s, so too did efforts for women’s rights. These efforts came to a head at an event that took place in London in 1840. That year, Lucretia Mott was among the American delegates attending the World Antislavery Convention in London. However, due to ideological disagreements between some of the abolitionists, the convention’s organizers refused to seat the female delegates or allow them to vote during the proceedings. Angered by this treatment, Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whose husband was also a delegate, returned to the United States with a renewed interest in pursuing women’s rights. In 1848, they organized the Seneca Falls Convention, a two-day summit in New York state in which women’s rights advocates came together to discuss the problems facing women.

Lucretia Mott campaigned for women’s rights, abolition, and equality in the United States. Joseph Kyle (artist), Lucretia Mott, 1842. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mott_Lucretia_Painting_Kyle_1841.jpg.

Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments for the Seneca Falls Convention in the hopes that it would encapsulate the wide range of issues that the early woman’s rights movement embraced. Modeled on the Declaration of Independence in order to emphasize the belief that women’s rights were part of the same democratic promises on which the United States was founded, it outlined fifteen grievances and eleven resolutions designed to promote women’s access to civil rights. Among these were issues including married women’s right to property, access to the professions, and, most controversially, the right to vote. Sixty-eight women and thirty-two men, all of whom were already involved in some aspect of reform, signed the Declaration of Sentiments. ((“Declaration of Sentiments,” in Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 1 (Rochester, N.Y.: Fowler and Wells, 1889), pages 70-71. http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/senecafalls.asp.))

Above all else, antebellum women’s rights advocates sought civil equality for men and women. They fought what they perceived as senseless gender discrimination, such as barring women from attending college or paying female teachers less than their male colleagues, and they argued that men and women should be held to the same moral standards. The Seneca Falls Convention was the first of many similar gatherings promoting women’s rights across the northern states. Yet the women’s rights movement grew slowly, and experienced few victories: few states reformed married women’s property laws before the Civil War, and no state was prepared to offer women the right to vote during the antebellum period. At the onset of the Civil War, women’s rights advocates temporarily threw all of their support behind abolition, allowing the cause of racial equality to temporarily trump that of gender equality. But the words of the Seneca Falls convention continued to inspire activists for generations.

VII. Conclusion

By the time civil war erupted in 1861, the revival and reform movements of the antebellum period had made an indelible mark on the American landscape. The Second Great Awakening ignited Protestant spirits by connecting evangelical Christians in national networks of faith. The social reform encouraged within such networks spurred members of the middle class to promote national morality and the public good. Not all reform projects were equally successful, however. While the temperance movement made substantial inroads against the excesses of alcohol consumption, the abolitionist movement proved so divisive that it paved the way for sectional crisis. Yet participation in reform movements, regardless of their ultimate success, encouraged many Americans to see themselves in new ways. Black activists became a powerful voice in antislavery societies, for example, developing domestic and transnational connections through which to pursue the cause of liberty. Middle-class women’s dominant presence in the benevolent empire encouraged them to pursue a full-fledged women’s right movement that has lasted in various forms up through the present day. In their efforts to make the United States a more virtuous and moral nation, nineteenth-century reform activists developed cultural and institutional foundations for social change that have continued to reverberate through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Contributors

This chapter was edited by Emily Conroy-Krutz, with content contributions by Elena Abbott, Cameron Blevins, Frank Cirillo, Justin Clark, Emily Conroy-Krutz, Megan Falater, Nicolas Hoffmann, Christopher C. Jones, Jonathan Koefoed, Charles McCrary, William E. Skidmore, Kelly Weber, and Ben Wright.

Recommended Reading

- Berg, Barbara J. The Remembered Gates: Origins of American Feminism, The Woman and the City 1800-1860 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

- Boylan, Anne. The Origins of Women’s Activism: New York and Boston, 1797-1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolonia Press, 2002).

- Brekus, Catherine A. Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

- Dorsey, Bruce. Reforming Men and Women: Gender in the Antebellum City (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002).

- DuBois, Ellen. Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848-1869, new edition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999).

- Ginzberg, Lori. Women and the Work of Benevolence: Morality, Politics, and Class in the 19th Century United States (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).

- Ginzberg, Lori. Untidy Origins: A Story of Woman’s Rights in Antebellum New York (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

- Hatch, Nathan O. The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989).

- Hempton, David Methodism: Empire of the Spirit (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

- Hewitt, Nancy. Women’s Activism and Social Change: Rochester, New York 1822-1872 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984).

- Jeffrey, Julie Roy. The Great Silent Army of Abolitionism: Ordinary Women in the Antislavery Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990).

- Johnson, Paul. A Shopkeepers Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815-1837, 25th anniversary edition (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004).

- Juster, Susan. Disorderly Women: Sexual Politics and Evangelicalism in Revolutionary New England (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994).

- Makdisi, Ussama. Artillery of Heaven: American Missionaries and the Failed Conversion of the Middle East (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008).

- McDaniel, W. Caleb. The Problem of Democracy in the Age of Slavery: Garrisonian Abolitionists and Transatlantic Reform (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013).

- Muncy, Raymond Lee. Sex and Marriage in Utopian Communities: 19th Century America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973).

- Ryan, Mary. Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family in Oneida County, New York, 1790-1865 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

- Ryan, Susan M. The Grammar of Good Intentions: Race and the Antebellum Culture of Benevolence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003).

- Stewart, James Brewer. Holy Warriors: The Abolitionists and American Slavery, revised edition (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996).

- Tomek, Beverly C. Colonization and Its Discontents: Emancipation, Emigration, and Antislavery in Antebellum Pennsylvania (New York: New York University Press, 2011).

- Walters, Ronald. American Reformers, 1815-1860, revised edition (New York: Hill and Wang, 1997).