Collecting the Dead. Cold Harbor, Virginia. April, 1865. Library of Congress.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

The American Civil War, the bloodiest in the nation’s history, resulted in approximately 750,000 deaths.1 The war touched the life of nearly every American as military mobilization reached levels never seen before or since. Most northern soldiers went to war to preserve the Union, but the war ultimately transformed into a struggle to eradicate slavery. African Americans, both enslaved and free, pressed the issue of emancipation and nurtured this transformation. Simultaneously, women thrust themselves into critical wartime roles while navigating a world without many men of military age. The Civil War was a defining event in the history of the United States and, for the Americans thrust into it, a wrenching one.

II. The Election of 1860 and Secession

The 1860 presidential election was chaotic. In April, the Democratic Party convened in Charleston, South Carolina, the bastion of secessionist thought in the South. The goal was to nominate a candidate for the party ticket, but the party was deeply divided. Northern Democrats pulled for Senator Stephen Douglas, a champion of popular sovereignty, while southern Democrats were intent on endorsing someone other than Douglas. The parties leaders’ refusal to include a pro-slavery platform resulted in southern delegates walking out of the convention, preventing Douglas from gaining the two-thirds majority required for a nomination. The Democrats ended up with two presidential candidates. A subsequent convention in Baltimore nominated Douglas, while southerners nominated the current vice president, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, as their presidential candidate. The nation’s oldest party had split over differences in policy toward slavery.2

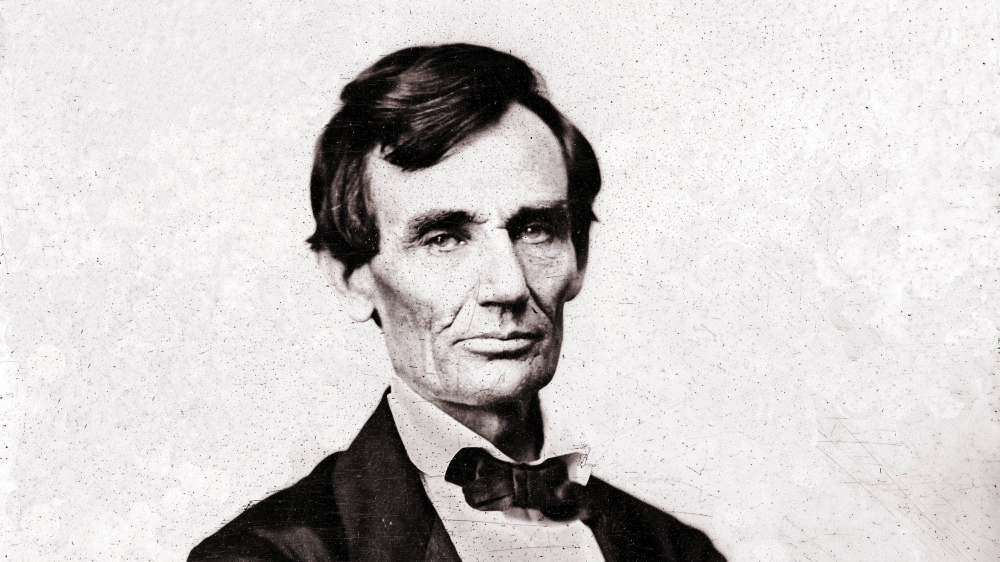

Initially, the Republicans were hardly unified around a single candidate themselves. Several leading Republican men vied for their party’s nomination. A consensus emerged at the May 1860 convention that the party’s nominee would need to carry all the free states—for only in that situation could a Republican nominee potentially win. New York Senator William Seward, a leading contender, was passed over. Seward’s pro-immigrant position posed a potential obstacle, particularly in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, as a relatively unknown but likable politician, rose from a pool of potential candidates and was selected by the delegates on the third ballot. The electoral landscape was further complicated through the emergence of a fourth candidate, Tennessee’s John Bell, heading the Constitutional Union Party. The Constitutional Unionists, composed of former Whigs who teamed up with some southern Democrats, made it their mission to avoid the specter of secession while doing little else to address the issues tearing the country apart.

Abraham Lincoln’s nomination proved a great windfall for the Republican Party. Lincoln carried all free states with the exception of New Jersey (which he split with Douglas). Of the voting electorate, 81.2 percent came out to vote—at that point the highest ever for a presidential election. Lincoln received less than 40 percent of the popular vote, but with the field so split, that percentage yielded 180 electoral votes. Lincoln was trailed by Breckinridge with his 72 electoral votes, carrying eleven of the fifteen slave states; Bell came in third with 39 electoral votes; and Douglas came in last, only able to garner 12 electoral votes despite carrying almost 30 percent of the popular vote. Since the Republican platform prohibited the expansion of slavery in future western states, all future Confederate states, with the exception of Virginia, excluded Lincoln’s name from their ballots.3

Abraham Lincoln, August 13, 1860. Library of Congress.

The election of Lincoln and the perceived threat to the institution of slavery proved too much for the deep southern states. South Carolina acted almost immediately, calling a convention to declare secession. On December 20, 1860, the South Carolina convention voted unanimously 169–0 to dissolve their union with the United States.4 The other states across the Deep South quickly followed suit. Mississippi adopted their own resolution on January 9, 1861, Florida followed on January 10, Alabama on January 11, Georgia on January 19, Louisiana on January 26, and Texas on February 1. Texas was the only state to put the issue up for a popular vote, but secession was widely popular throughout the South.

Confederates quickly shed their American identity and adopted a new Confederate nationalism. Confederate nationalism was based on several ideals, foremost among these being slavery. As Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens stated, the Confederacy’s “foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery . . . is his natural and normal condition.”5 The election of Lincoln in 1860 demonstrated that the South was politically overwhelmed. Slavery was omnipresent in the prewar South, and it served as the most common frame of reference for unequal power. To a southern man, there was no fate more terrifying than the thought of being reduced to the level of a slave. Religion likewise shaped Confederate nationalism, as southerners believed that the Confederacy was fulfilling God’s will. The Confederacy even veered from the American constitution by explicitly invoking Christianity in their founding document. Yet in every case, all rationale for secession could be thoroughly tied to slavery. “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world,” proclaimed the Mississippi statement of secession.6 Thus for the original seven Confederate states (and the four that would subsequently join), slavery’s existence was the essential core of the fledging Confederacy.

The emblems of nationalism on this currency reveal much about the ideology underpinning the Confederacy: George Washington standing stately in a Roman toga indicates the belief in the South’s honorable and aristocratic past; John C. Calhoun’s portrait emphasizes the Confederate argument of the importance of states’ rights; and, most importantly, the image of African Americans working in fields demonstrates slavery’s position as foundational to the Confederacy. A five and one hundred dollar Confederate States of America interest-bearing banknote, c. 1861 and 1862. Wikimedia.

Not all southerners participated in Confederate nationalism. Unionist southerners, most common in the upcountry where slavery was weakest, retained their loyalty to the Union. These southerners joined the Union army, that is, the army of the United States of America, and worked to defeat the Confederacy.7 Black southerners, most of whom were enslaved, overwhelmingly supported the Union, often running away from plantations and forcing the Union army to reckon with slavery.8

President James Buchanan would not directly address the issue of secession prior to his term’s end in early March. Any effort to try to solve the issue therefore fell upon Congress, specifically a Committee of Thirteen including prominent men such as Stephen Douglas, William Seward, Robert Toombs, and John Crittenden. In what became known as “Crittenden’s Compromise,” Senator Crittenden proposed a series of Constitutional amendments that guaranteed slavery in southern states and territories, denied the federal government interstate slave trade regulatory power, and offered to compensate enslavers whose enslaved people had escaped. The Committee of Thirteen ultimately voted down the measure, and it likewise failed in the full Senate vote (25–23). Reconciliation appeared impossible.9

The seven seceding states met in Montgomery, Alabama on February 4 to organize a new nation. The delegates selected Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as president and established a capital in Montgomery, Alabama (it would move to Richmond in May). Whether other states of the Upper South would join the Confederacy remained uncertain. By the early spring of 1861, North Carolina and Tennessee had not held secession conventions, while voters in Virginia, Missouri, and Arkansas initially voted down secession. Despite this temporary boost to the Union, it became abundantly clear that these acts of loyalty in the Upper South were highly conditional and relied on a clear lack of intervention on the part of the federal government. This was the precarious political situation facing Abraham Lincoln following his inauguration on March 4, 1861.

III. A War for Union 1861-1863

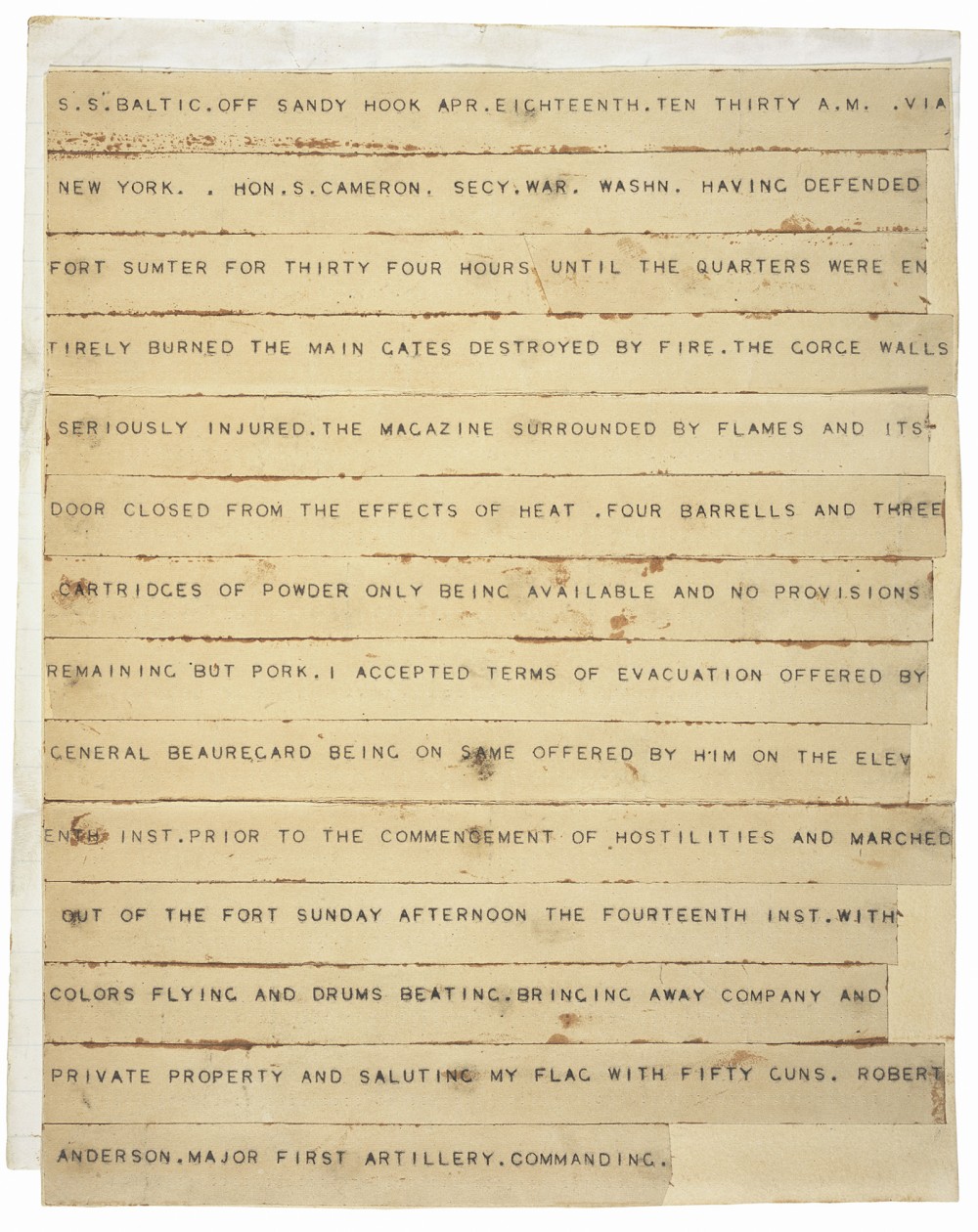

In his inaugural address, Lincoln declared secession “legally void.”10 While he did not intend to invade southern states, he would use force to maintain possession of federal property within seceded states. Attention quickly shifted to the federal installation of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. The fort was in need of supplies, and Lincoln intended to resupply it. South Carolina called for U.S. soldiers to evacuate the fort. Commanding officer Major Robert Anderson refused. On April 12, 1861, Confederate Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard fired on the fort. Anderson surrendered on April 13 and the Union troops evacuated. In response to the attack, President Abraham Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand volunteers to serve three months to suppress the rebellion. The American Civil War had begun.

Sent to then Secretary of War Simon Cameron on April 13, 1861, this telegraph announced that after “thirty hours of defending Fort Sumter, Major Robert Anderson had accepted the evacuation offered by Confederate General Beauregard. The Union had surrendered Fort Sumter, and the Civil War had officially begun. “Telegram from Maj. Robert Anderson to Hon. Simon Cameron, Secretary, announcing his withdrawal from Fort Sumter,” April 18, 1861; Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917; Record Group 94. National Archives

The assault on Fort Sumter and subsequent call for troops provoked several Upper South states to join the Confederacy. In total, eleven states renounced their allegiance to the United States. The new Confederate nation was predicated on the institution of slavery and the promotion of any and all interests that reinforced that objective. Some southerners couched their defense of slavery as a preservation of states’ rights. But in order to protect slavery, the Confederate constitution left even less power to the states than the U.S. Constitution, an irony not lost on many.

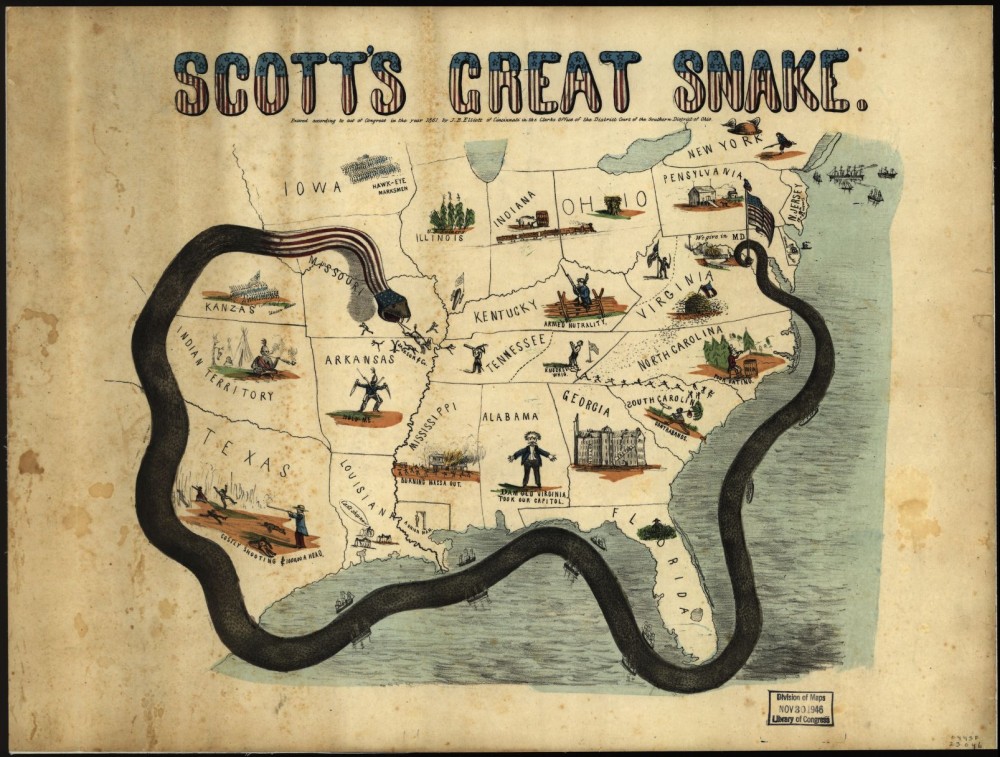

Shortly after Lincoln’s call for troops, the Union adopted General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan to suppress the rebellion. This strategy intended to strangle the Confederacy by cutting off access to coastal ports and inland waterways via a naval blockade. Ground troops would enter the interior. Like an anaconda snake, they planned to surround and squeeze the Confederacy.

Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan meant to slowly squeeze the South dry of its resources, blocking all coastal ports and inland waterways to prevent the importation of goods or the export of cotton. This print, while poorly drawn, does a great job of making clear the Union’s plan. J.B. Elliott, Scott’s great snake. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1861, 1861. Library of Congress.

The border states of Delaware, Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky maintained geographic, social, political, and economic connections to both the North and the South. All four were immediately critical to the outcome of the conflict. Maryland was particularly important given its position relative to Washington DC. Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus and allowed military commanders to arrest secession-friendly activists without charging them with a crime. Other border states were also important, and Lincoln famously quipped, “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game.”11 Lincoln and his military advisors realized that the loss of the border states could mean a significant decrease in Union resources and threaten the capital in Washington. Consequently, Lincoln hoped to foster loyalty among their citizens, so Union forces could minimize their occupation. In spite of terrible guerrilla warfare in Missouri and Kentucky, the four border states remained loyal to the Union throughout the war.

Foreign countries, primarily in Europe, also watched the unfolding war with deep interest. The United States represented the greatest example of democratic thought at the time, and individuals from as far afield as Britain, France, Spain, Russia, and beyond closely followed events across the Atlantic Ocean. If the democratic experiment within the United States failed, many democratic activists in Europe wondered what hope might exist for such experiments elsewhere. Conversely, those with close ties to the cotton industry watched with other concerns. War meant the possibility of disrupting the cotton supply, and disruption could have catastrophic ramifications in commercial and financial markets abroad.

While Lincoln, his cabinet, and the War Department devised strategies to defeat the rebel insurrection, Black Americans quickly forced the issue of slavery as a primary issue in the debate. As early as 1861, Black Americans implored the Lincoln administration to serve in the army and navy.12 Lincoln initially waged a conservative, limited war. He believed that the presence of African American troops would threaten the loyalty of slaveholding border states, and white volunteers might refuse to serve alongside Black men. However, army commanders could not ignore the growing populations of formerly enslaved people who escaped to freedom behind Union army lines. These former enslaved people took a proactive stance early in the war and forced the federal government to act. As the number of refugees ballooned, Lincoln and Congress found it harder to avoid the issue.13

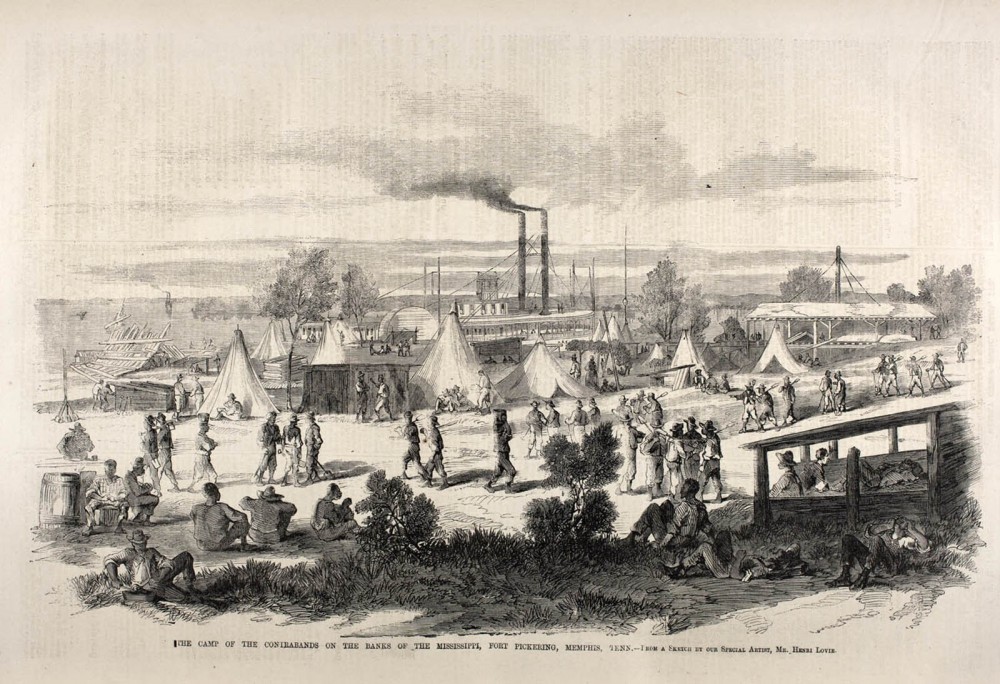

In May 1861, General Benjamin F. Butler went over his superiors’ heads and began accepting freedom-seeking escapees who came to Fort Monroe in Virginia. In order to avoid answering whether these people were free, Butler reasoned called them “contraband of war,” and he had as much a right to seize them as he did to seize enemy horses or cannons.14 Later that summer Congress affirmed Butler’s policy in the First Confiscation Act. The act left “contrabands,” as these runaways were called, in a state of limbo. Once an enslaved person escaped to Union lines, their enslaver’s claim was nullified. She was not, however, a free citizen of the United States. Runaways lived in “contraband camps,” where disease and malnutrition were rampant. Women and men were required to perform the drudge work of war: raising fortifications, cooking meals, and laying railroad tracks. Still, life as a contraband offered a potential path to freedom, and thousands of enslaved people seized the opportunity.

Enslaved African Americans who took freedom into their own hands and ran to Union lines congregated in what were called contraband camps, which existed alongside Union army camps. As is evident in the drawing, these were crude, disorganized, and dirty places. But they were still centers of freedom for those fleeing slavery. Contraband camp, Richmond, Va, 1865. The Camp of the Contrabands on the Banks of the Mississippi, Fort Pickering, Memphis, Tenn, 1862. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

Fugitives posed a dilemma for the Union military. Soldiers were forbidden to interfere with slavery or assist runaways, but many soldiers found such a policy unchristian. Even those indifferent to slavery were reluctant to turn away potential laborers or help the enemy by returning his property. Also, enslaved people could provide useful information on the local terrain and the movements of Confederate troops. Union officers became particularly reluctant to turn away freedom-seeking people when Confederate commanders began forcing enslaved laborers to work on fortifications. Every enslaved person who escaped to Union lines was a loss to the Confederate war effort.

Any hopes for a brief conflict were eradicated when Union and Confederate forces met at the Battle of Bull Run, near Manassas, Virginia. While not particularly deadly, the Confederate victory proved that the Civil War would be long and costly. Furthermore, in response to the embarrassing Union rout, Lincoln removed Brigadier General Irvin McDowell and promoted Major General George B. McClellan to commander of the newly formed Army of the Potomac. For nearly a year after the First Battle of Bull Run, the Eastern Theater remained relatively silent. Smaller engagements only resulted in a bloody stalemate.

Photography captured the horrors of war as never before. Some Civil War photographers arranged the actors in their frames to capture the best picture, even repositioning bodies of dead soldiers for battlefield photos. Alexander Gardner, [Antietam, Md. Confederate dead by a fence on the Hagerstown road], September 1862. Library of Congress.

New and more destructive warfare technology emerged during this time that utilized discoveries and innovations in other areas of life, like transportation. This photograph shows Robert E. Lee’s railroad gun and crew used in the main eastern theater of war at the siege of Petersburg, June 1864-April 1865. “Petersburg, Va. Railroad gun and crew,” between 1864 and 1865. Library of Congress.

The Democratic Party, absent its southern leaders, divided into two camps. War Democrats largely stood behind President Lincoln. Peace Democrats—also known as Copperheads—clashed frequently with both War Democrats and Republicans. Copperheads were sympathetic to the Confederacy; they exploited public antiwar sentiment (often the result of a lost battle or mounting casualties) and tried to push President Lincoln to negotiate an immediate peace, regardless of political leverage or bargaining power. Had the Copperheads succeeded in bringing about immediate peace, the Union would have been forced to recognize the Confederacy as a separate and legitimate government and the institution of slavery would have remained intact.

While Washington buzzed with political activity, military life consisted of relative monotony punctuated by brief periods of horror. Daily life for a Civil War soldier was one of routine. A typical day began around six in the morning and involved drill, marching, lunch break, and more drilling followed by policing the camp. Weapon inspection and cleaning followed, perhaps one final drill, dinner, and taps around nine or nine thirty in the evening. Soldiers in both armies grew weary of the routine. Picketing or foraging afforded welcome distractions to the monotony.

Soldiers devised clever ways of dealing with the boredom of camp life. The most common was writing. These were highly literate armies; nine out of every ten Federals and eight out of every ten Confederates could read and write.16 Letters home served as a tether linking soldiers to their loved ones. Soldiers also read; newspapers were in high demand. News of battles, events in Europe, politics in Washington and Richmond, and local concerns were voraciously sought and traded.

While there were nurses, camp followers, and some women who disguised themselves as men, camp life was overwhelmingly male. Soldiers drank liquor, smoked tobacco, gambled, and swore. Social commentators feared that when these men returned home, with their hard-drinking and irreligious ways, all decency, faith, and temperance would depart. But not all methods of distraction were detrimental. Soldiers also organized debate societies, composed music, sang songs, wrestled, raced horses, boxed, and played sports.

Neither side could consistently provide supplies for their soldiers, so it was not uncommon, though officially forbidden, for common soldiers to trade with the enemy. Confederate soldiers prized northern newspapers and coffee. Northerners were glad to exchange these for southern tobacco. Supply shortages and poor sanitation were synonymous with Civil War armies. The close proximity of thousands of men bred disease. Lice were soldiers’ daily companions.

Music was popular among the soldiers of both armies, creating a diversion from the boredom and horror of the war. As a result, soldiers often sang on fatigue duty and while in camp. Favorite songs often reminded the soldiers of home, including “Lorena,” “Home, Sweet Home,” and “Just Before the Battle, Mother.” Dances held in camp offered another way to enjoy music. Since there were often few women nearby, soldiers would dance with one another.

When the Civil War broke out, one of the most popular songs among soldiers and civilians was “John Brown’s Body,” which began “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave.” Started as a Union anthem praising John Brown’s actions at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, then used by Confederates to vilify Brown, both sides’ version of the song stressed that they were on the right side. Eventually the words to Julia Ward Howe’s poem “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” were set to the melody, further implying Union success. The themes of popular songs changed over the course of the war, as feelings of inevitable success alternated with feelings of terror and despair.17

After an extensive delay on the part of Union commander George McClellan, his 120,000-man Army of the Potomac moved via ship to the peninsula between the York and James Rivers in Virginia. Rather than crossing overland via the former battlefield at Manassas Junction, McClellan attempted to swing around the rebel forces and enter the capital of Richmond before they knew what hit them. McClellan, however, was an overly cautious man who consistently overestimated his adversaries’ numbers. This cautious approach played into the Confederates’ favor on the outskirts of Richmond. Confederate General Robert E. Lee, recently appointed commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, forced McClellan to retreat from Richmond, and his Peninsular Campaign became a tremendous failure.18

Union forces met with little success in the East, but the Western Theater provided hope for the United States. In February 1862, men under Union general Ulysses S. Grant captured Forts Henry and Donelson along the Tennessee River. Fighting in the West greatly differed from that in the East. At the First Battle of Bull Run, for example, two large armies fought for control of the nations’ capitals, while in the West, Union and Confederate forces fought for control of the rivers, since the Mississippi River and its tributaries were key components of the Union’s Anaconda Plan. One of the deadliest of these clashes occurred along the Tennessee River at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6–7, 1862. This battle, lasting only two days, was the costliest single battle in American history up to that time. The Union victory shocked both the Union and the Confederacy with approximately twenty-three thousand casualties, a number that exceeded casualties from all of the United States’ previous wars combined.19 The subsequent capture of New Orleans by Union forces proved a heavy blow to the Confederacy and capped an 1862 spring of success in the Western Theater.

The Union and Confederate navies helped or hindered army movements around the many marine environments of the southern United States. Each navy employed the latest technology to outmatch the other. The Confederate navy, led by Stephen Russell Mallory, had the unenviable task of constructing a fleet from scratch and trying to fend off a vastly better equipped Union navy. Led by Gideon Welles of Connecticut, the Union navy successfully implemented General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan. The future of naval warfare also emerged in the spring of 1862 as two “ironclad” warships fought a duel at Hampton Roads, Virginia. The age of the wooden sail was gone and naval warfare would be fundamentally altered. While advances in naval technology ruled the seas, African Americans on the ground were complicating Union war aims to an even greater degree.

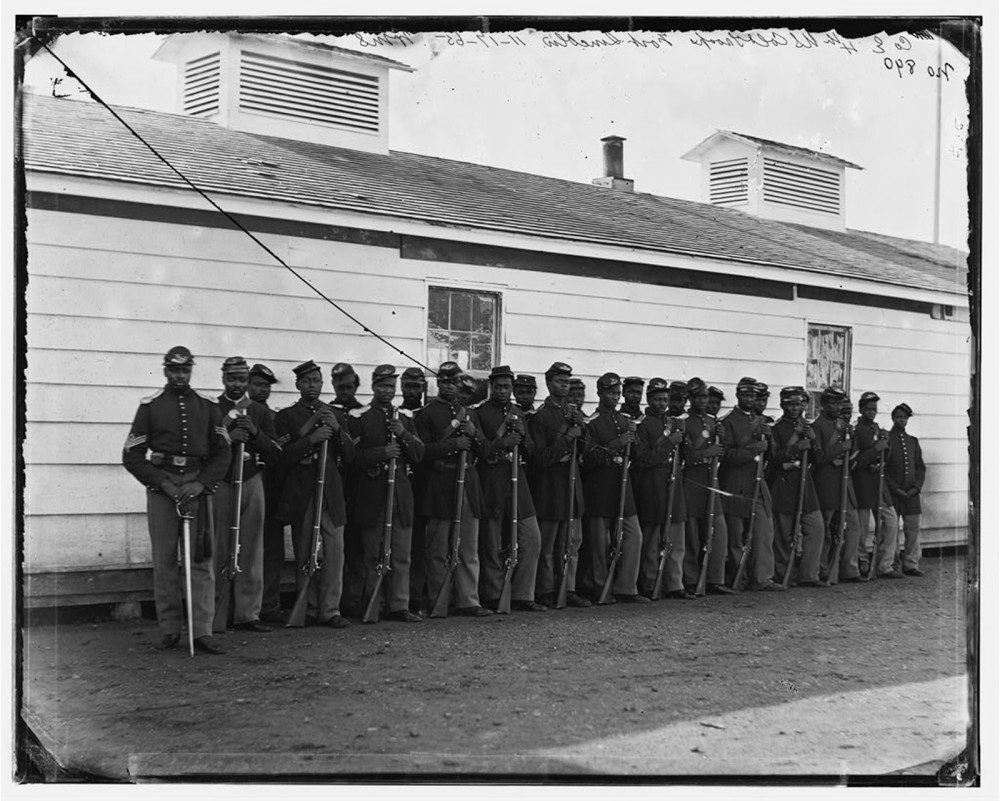

The creation of Black regiments was another kind of innovation during the Civil War. Northern free Black men and newly freed men joined together under the leadership of white officers to fight for the Union cause. This novelty was not only beneficial for the Union war effort; it also showed the Confederacy that the Union sought to destroy the foundational institution (slavery) upon which their nation was built. William Morris Smith, [District of Columbia. Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln], between 1863 and 1866. Library of Congress.

![This African American family dressed in their finest clothes (including a USCT uniform) for this photograph, projecting respectability and dignity that was at odds with the southern perception of black Americans. “[Unidentified African American soldier in Union uniform with wife and two daughters],” between 1863 and 1865. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010647216/.](http://www.americanyawp.com/text/wp-content/uploads/36454v-1000x845.jpg)

This African American family dressed in their finest clothes (including a USCT uniform) for this photograph, projecting respectability and dignity that was at odds with the southern perception of Black Americans. [Unidentified African American soldier in Union uniform with wife and two daughters], between 1863 and 1865. Library of Congress.

Despite the Confederate withdrawal and the high death toll, the Battle of Antietam was not a decisive Union victory. It did, however, result in enough of a victory for Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed enslaved people in areas under Confederate control. There were significant exemptions to the Emancipation Proclamation, including the border states and parts of other states in the Confederacy. A far cry from a universal end to slavery, the Emancipation Proclamation nevertheless proved vital, shifting the war’s aims from simple union to emancipation. Framing it as a war measure, Lincoln and his cabinet hoped that stripping the Confederacy of its labor force would not only debilitate the southern economy but also weaken Confederate morale. Furthermore, the Battle of Antietam and the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation all but ensured that the Confederacy would not be recognized by European powers. Nevertheless, Confederates continued fighting. Union and Confederate forces clashed again at Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862. This Confederate victory resulted in staggering Union casualties.

IV. War for Emancipation 1863-1865

As Union armies penetrated deeper into the Confederacy, politicians and generals came to understand the necessity and benefit of enlisting Black men in the army and navy. Although a few commanders began forming Black units in 1862, such as Massachusetts abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s First South Carolina Volunteers (the first regiment of Black soldiers), widespread enlistment did not occur until the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863. “And I further declare and make known,” Lincoln’s proclamation read, “that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”21

The language describing Black enlistment indicated Lincoln’s implicit desire to segregate African American troops from the main campaigning armies of white soldiers. “I believe it is a resource which, if vigorously applied now, will soon close the contest. It works doubly, weakening the enemy and strengthening us,” Lincoln remarked in August 1863 about Black soldiering.22 Although more than 180,000 Black men (10 percent of the Union army) served during the war, the majority of United States Colored Troops (USCT) remained stationed behind the lines as garrison forces, often laboring and performing noncombat roles.

Black soldiers in the Union army endured rampant discrimination and earned less pay than white soldiers, while also facing the possibility of being murdered or sold into slavery if captured. James Henry Gooding, a Black corporal in the famed 54th Massachusetts Volunteers, wrote to Abraham Lincoln in September 1863, questioning why he and his fellow volunteers were paid less than white men. Gooding argued that because he and his brethren were born in the United States and selflessly left their private lives to enter the army, they should be treated “as American SOLDIERS, not as menial hirelings.”23

African American soldiers defied the inequality of military service and used their positions in the army to reshape society, North and South. The majority of the USCT had once been enslaved, and their presence as armed, blue-clad soldiers sent shock waves throughout the Confederacy. To their friends and families, African American soldiers symbolized the embodiment of liberation and the destruction of slavery. To white southerners, they represented the utter disruption of the Old South’s racial and social hierarchy. As members of armies of occupation, Black soldiers wielded martial authority in towns and plantations. At the end of the war, as a Black soldier marched by a cluster of Confederate prisoners, he noticed his former enslaver among the group. “Hello, massa,” the soldier exclaimed, “bottom rail on top dis time!”24

“Two Brothers in Arms.” The Library of Congress.

The majority of the USCT occupied the South by performing garrison duty; other Black soldiers performed admirably on the battlefield, shattering white myths that docile, cowardly Black men would fold in the maelstrom of war. Black troops fought in more than four hundred battles and skirmishes, including Milliken’s Bend and Port Hudson, Louisiana; Fort Wagner, South Carolina; Nashville; and the final campaigns to capture Richmond, Virginia. Fifteen Black soldiers received the Medal of Honor, the highest honor bestowed for military heroism. Through their voluntarism, service, battlefield contributions, and even death, Black soldiers laid their claims for citizenship. “Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letter U.S.” Frederick Douglass, the great Black abolitionist, proclaimed, “and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”25

Many enslaved laborers accompanied their enslavers in the Confederate army. They served their enslavers as “camp servants,” cooking their meals, raising their tents, and carrying their supplies. The Confederacy also impressed enslaved laborers to perform manual labor. There are three important points to make about these enslaved “Confederates.” First, their labor was almost always coerced. Second, people are complicated and have varying, often contradictory loyalties. An enslaved person could hope in general that the Confederacy would lose but at the same time be concerned for the safety of his enslaver and the Confederate soldiers he saw on a daily basis.

Finally, white Confederates did not see African Americans as their equals, much less as soldiers. There was never any doubt that Black laborers and camp servants were property. Though historians disagree on the matter, it is a stretch to claim that not a single African American ever fired a gun for the Confederacy; a camp servant whose enslaver died in battle might well pick up his dead enslaver’s gun and continue firing, if for no other reason than to protect himself. But this was always on an informal basis. The Confederate government did, in an act of desperation, pass a law in March 1865 allowing for the enlistment of Black soldiers, but only a few dozen African Americans (mostly Richmond hospital workers) had enlisted by the war’s end.

As 1863 dawned, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia continued its offensive strategy in the East. One of the war’s major battles occurred near the village of Chancellorsville, Virginia, between April 30 and May 6, 1863. While the Battle of Chancellorsville was an outstanding Confederate victory, it also resulted in heavy casualties and the mortal wounding of Confederate major general “Stonewall” Jackson, who was killed by friendly fire.

In spite of Jackson’s death, Lee continued his offensive against federal forces and invaded Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863. During the three-day battle (July 1–3) at Gettysburg, heavy casualties crippled both sides. Yet the devastating July 3 infantry assault on the Union center, also known as Pickett’s Charge, caused Lee to retreat from Pennsylvania. The Gettysburg Campaign was Lee’s final northern incursion and the Battle of Gettysburg remains the bloodiest battle of the war, and in American history, with fifty-one thousand casualties.

Concurrently in the West, Union forces continued their movement along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Grant launched his campaign against Vicksburg, Mississippi, in the winter of 1862. Known as the “Gibraltar of the West,” Vicksburg was the last holdout in the West, and its seizure would enable uninhibited travel for Union forces along the Mississippi River. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign, which lasted until July 4, 1863, ended with the city’s surrender. The fall of Vicksburg split the Confederacy in two.

Despite Union success in the summer of 1863, discontent over the war simmered across the North. This was particularly true in the wake of the Enrollment Act—the first effort at a draft among the northern populace during the Civil War. Working-class northerners were especially angry that the wealthy could pay $300 for substitutes, sparing themselves from the carnage of war. “A rich man’s war, but a poor man’s fight,” was a popular refrain.26 The Emancipation Proclamation convinced many immigrants in northern cities that freed people would soon take their jobs. These economic and racial anxieties culminated in the New York City Draft Riots in July 1863. Over the span of four days, white rioters killed some 120 citizens, including the lynching of at least eleven Black New Yorkers. Property damage was in the millions, including the complete destruction of more than fifty properties—most notably that of the Colored Orphan Asylum. It was the largest civil disturbance to date in the United States (aside from the war itself) and was only stopped by the deployment of Union soldiers, some of whom came directly from the battlefield at Gettysburg.

Elsewhere, the North produced widespread displays of unity. Sanitary fairs originated in the Old Northwest and raised millions of dollars for Union soldiers. Indeed, many women rose to take pivotal leadership roles in the sanitary fairs—a clear contribution to the northern war effort. The fairs also encouraged national unity within the North—something that became more important as the war dragged on and casualties continued to mount. The northern homefront was complicated: overt displays of loyalty contrasted with violent dissent.

Thomas Nast, “Our Heroines, United States Sanitary Commission,” in Harper’s Weekly, April 9, 1864. Cushing/Whitney Medical Library at Yale University.

A similar situation played out in the Confederacy. The Confederate Congress passed its first conscription act in the spring of 1862, a full year before its northern counterpart. Military service was required from all able-bodied males between ages eighteen and thirty-five (eventually extended to forty-five). Notable class exemptions likewise existed in the Confederacy: those who owned twenty or more enslaved laborers could escape the draft. Popular discontent reached a boiling point in 1863. Through the spring of 1863 consistent food shortages led to “bread riots” in several Confederate cities, most notably Richmond, Virginia, and the Georgia cities of Augusta, Macon, and Columbus. Confederate women led these mobs to protest food shortages and rampant inflation within the Confederate South. Exerting their own political control, women dramatically impacted the war through violent actions in these cases, as well as constant petitions to governors for aid and the release of husbands from military service. One of these women wrote a letter to North Carolina governor Zebulon Vance, saying, “Especially for the sake of suffering women and children, do try and stop this cruel war.”27 Confederates waged a multifront struggle against Union incursion and internal dissent.

For some women, the best way to support their cause was spying on the enemy. When the war broke out, Rose O’Neal Greenhow was living in Washington, D.C., where she traveled in high social circles, gathering information for her Confederate contact. Suspecting Greenhow of espionage, Allan Pinkerton placed her under surveillance, instigated a raid on her house to gather evidence, and then placed her under house arrest, after which she was incarcerated in Old Capitol Prison. Upon her release, she was sent, under guard, to Baltimore, Maryland. From there Greenhow went to Europe to attempt to bring support to the Confederacy. Failing in her efforts, Greenhow decided to return to America, boarding the blockade runner Condor, which ran aground near Wilmington, North Carolina. Subsequently, she drowned after her lifeboat capsized in a storm. Greenhow gave her life for the Confederate cause, while Elizabeth “Crazy Bet” Van Lew sacrificed her social standing for the Union. Van Lew was from a prominent Richmond, Virginia, family and spied on the Confederacy, leading to her being “held in contempt & scorn by the narrow minded men and women of my city for my loyalty.”28 Indeed, when General Ulysses Grant took control of Richmond, he placed a special guard on Van Lew. In addition to her espionage activities, Van Lew also acted as a nurse to Union prisoners in Libby Prison. For pro-Confederate southern women, there were more opportunities to show their scorn for the enemy. Some women in New Orleans took these demonstrations to the level of dumping their chamber pots onto the heads of unsuspecting federal soldiers who stood underneath their balconies, leading to Benjamin Butler’s infamous General Order Number 28, which arrested all rebellious women as prostitutes.

Pauline Cushman was an American actress and a wartime spy. Using her guile to fraternize with Confederate officers, Cushman snuck military plans and drawings to Union officials in her shoes. She was caught, tried, and sentenced to death, but was apparently saved days before her execution by the occupation of her native New Orleans by Union forces. Whether as spies, nurses, or textile workers, women were essential to the Union war effort. “Pauline Cushman,” between 1855 and 1865. Library of Congress.

Military strategy shifted in 1864. The new tactics of “hard war” evolved slowly, as restraint toward southern civilians and property ultimately gave way to a concerted effort to demoralize southern civilians and destroy the southern economy. Grant’s successes at Vicksburg and Chattanooga, Tennessee (November 1863), and Meade’s cautious pursuit of Lee after Gettysburg prompted Lincoln to promote Grant to general-in-chief of the Union army in early 1864. This change in command resulted in some of the bloodiest battles of the Eastern Theater. Grant’s Overland Campaign, including the Battle of the Wilderness, the Battle of Cold Harbor, and the siege of Petersburg, demonstrated Grant’s willingness to tirelessly attack the ever-dwindling Army of Northern Virginia. By June 1864, Grant’s army surrounded the Confederate city of Petersburg, Virginia. Siege operations cut off Confederate forces and supplies from the capital of Richmond. Meanwhile out west, Union armies under the command of William Tecumseh Sherman implemented hard war strategies and slowly made their way through central Tennessee and northern Georgia, capturing the vital rail hub of Atlanta in September 1864.

Action in both theaters during 1864 caused even more casualties and furthered the devastation of disease. Disease haunted both armies, and accounted for over half of all Civil War casualties. Sometimes as many as half of the men in a company could be sick. The overwhelming majority of Civil War soldiers came from rural areas, where less exposure to diseases meant soldiers lacked immunities. Vaccines for diseases such as smallpox were largely unavailable to those outside cities or towns. Despite the common nineteenth-century tendency to see city men as weak or soft, soldiers from urban environments tended to succumb to fewer diseases than their rural counterparts. Tuberculosis, measles, rheumatism, typhoid, malaria, and smallpox spread almost unchecked among the armies.

Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery B, Petersburg, Virginia. Photograph by Timothy H. O’Sullivan, 1864. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

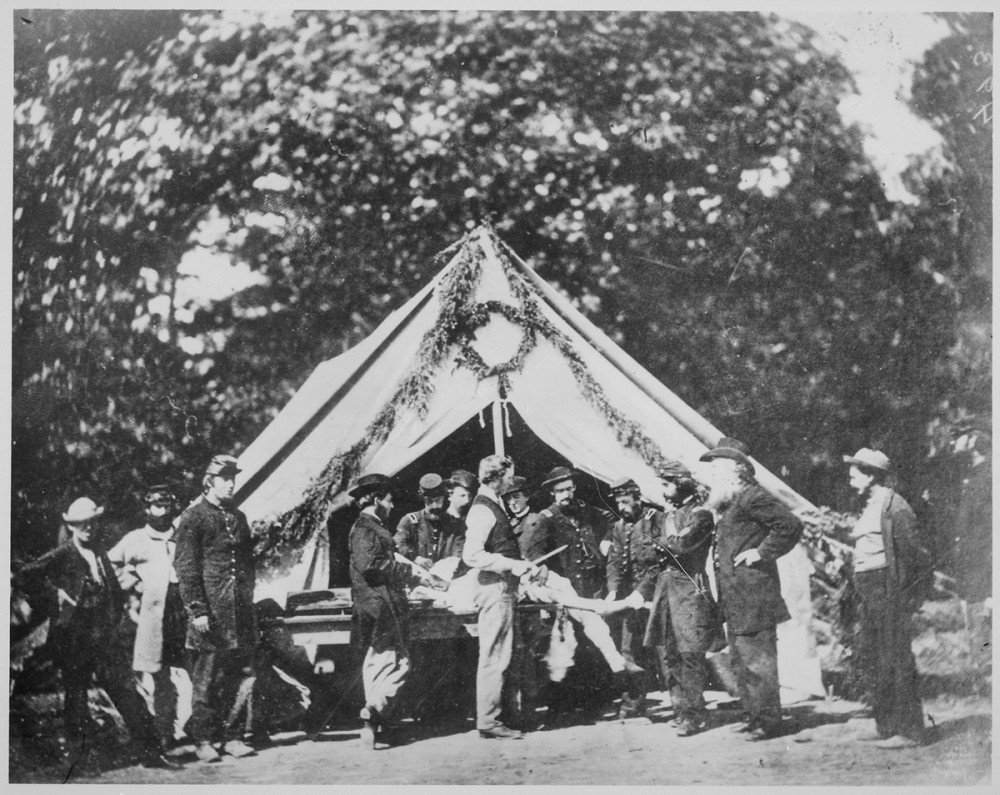

Civil War medicine focused almost exclusively on curing the patient rather than preventing disease. Many soldiers attempted to cure themselves by concocting elixirs and medicines themselves. These ineffective home remedies were often made from various plants the men found in woods or fields. There was no understanding of germ theory, so many soldiers did things that we would consider unsanitary today.29 They ate food that was improperly cooked and handled, and they practiced what we would consider poor personal hygiene. They did not take appropriate steps to ensure that drinking water was free from bacteria. Diarrhea and dysentery were common. These diseases were especially dangerous, as Civil War soldiers did not understand the value of replacing fluids as they were lost. As such, men affected by these conditions would weaken and become unable to fight or march, and as they became dehydrated their immune system became less effective, inviting other infections to attack the body. Through trial and error soldiers began to protect themselves from some of the more preventable sources of infection. Around 1862 both armies began to dig latrines rather than rely on the local waterways. Burying human and animal waste also cut down on exposure to diseases considerably.

Medical surgery was limited and brutal. If a soldier was wounded in the torso, throat, or head, there was little surgeons could do. Invasive procedures to repair damaged organs or stem blood loss invariably resulted in death. Luckily for soldiers, only approximately one in six combat wounds were to one of those parts. The remaining were to limbs, which was treatable by amputation. Soldiers had the highest chance of survival if the limb was removed within forty-eight hours of injury. A skilled surgeon could amputate a limb in three to five minutes from start to finish. While the lack of germ theory again caused several unsafe practices, such as using the same tools on multiple patients, wiping hands on filthy gowns, or placing hands in communal buckets of water, there is evidence that amputation offered the best chance of survival.

Amputations were a common form of treatment during the war. While it saved the lives of some soldiers, it was extremely painful and resulted in death in many cases. It also produced the first community of war veterans without limbs in American history. “Amputation being performed in a hospital tent, Gettysburg,” July 1863. National Archives and Records Administration.

It is a common misconception that amputation was done without anesthesia and against a patient’s wishes. Since the 1830s, Americans understood the benefits of nitrous oxide and ether in easing pain. Chloroform and opium were also used to either render patients unconscious or dull pain during the procedure. Also, surgeons would not amputate without the patient’s consent.

In the Union army alone, 2.8 million ounces of opium and over 5.2 million opium pills were administered. In 1862, William Alexander Hammon was appointed Surgeon General for the United States. He sought to regulate dosages and manage supplies of available medicines, both to prevent overdosing and to ensure that an ample supply remained for the next engagement. However, his guidelines tended to apply only to the regular federal army. Most Union soldiers were in volunteer units and organized at the state level. Their surgeons often ignored posted limits on medicines, or worse, experimented with their own concoctions made from local flora.

In the North, the conditions in hospitals were somewhat superior. This was partly due to the organizational skills of women like Dorothea Dix, who was the Union’s Superintendent for Army Nurses. Additionally, many women were members of the United States Sanitary Commission and helped to staff and supply hospitals in the North.

Women took on key roles within hospitals both North and South. The publisher’s notice for Nurse and Spy in the Union Army states, “In the opinion of many, it is the privilege of woman to minister to the sick and soothe the sorrowing—and in the present crisis of our country’s history, to aid our brothers to the extent of her capacity.”30 Mary Chesnut wrote, “Every woman in the house is ready to rush into the Florence Nightingale business.”31 However, she indicated that after she visited the hospital, “I can never again shut out of view the sights that I saw there of human misery. I sit thinking, shut my eyes, and see it all.”32 Hospital conditions were often so bad that many volunteer nurses quit soon after beginning. Kate Cumming volunteered as a nurse shortly after the war began. She, and other volunteers, traveled with the Army of Tennessee. However, all but one of the women who volunteered with Cumming quit within a week.

Death came in many forms; disease, prisons, bullets, even lightning and bee stings took men slowly or suddenly. Their deaths, however, affected more than their regiments. Before the war, a wife expected to sit at her husband’s bed, holding his hand, and ministering to him after a long, fulfilling life. This type of death, “the Good Death,” changed during the Civil War as men died often far from home among strangers.33 Casualty reporting was inconsistent, so a woman was often at the mercy of the men who fought alongside her husband to learn not only the details of his death but even that the death had occurred.

“Now I’m a widow. Ah! That mournful word. Little the world think of the agony it contains!” wrote Sally Randle Perry in her diary.34 After her husband’s death at Sharpsburg, Sally received the label she would share with more than two hundred thousand other women. The death of a husband and loss of financial, physical, and emotional support could shatter lives. It also had the perverse power to free women from bad marriages and open doors to financial and psychological independence.

Widows had an important role to play in the conflict. The ideal widow wore black, mourned for a minimum of two and a half years, resigned herself to God’s will, focused on her children, devoted herself to her husband’s memory, and brought his body home for burial. Many tried, but not all widows were able to live up to the ideal. Many were unable to purchase proper mourning garb. Black silk dresses, heavy veils, and other features of antebellum mourning were expensive and in short supply. Because most of these women were in their childbearing years, the war created an unprecedented number of widows who were pregnant or still nursing infants. In a time when the average woman gave birth to eight to ten children in her lifetime, it is perhaps not surprising that the Civil War created so many widows who were also young mothers with little free time for formal mourning. Widowhood permeated American society. But in the end, it was up to each widow to navigate her own mourning. She joined the ranks of sisters, mothers, cousins, girlfriends, and communities in mourning men.35

By the fall of 1864, military and social events played against the backdrop of the presidential election of 1864. While the war raged on, the presidential contest featured a transformed electorate. Three new states (West Virginia, Nevada, and Kansas) had been added since 1860, while the eleven states of the Confederacy did not participate. Lincoln and his vice presidential nominee, Andrew Johnson (Tennessee), ran on the National Union Party ticket. The main competition came from his former commander, General George B. McClellan. Though McClellan himself was a “War Democrat,” the official platform of the Democratic Party in 1864 revolved around negotiating an immediate end to the Civil War. McClellan’s vice presidential nominee was George H. Pendleton of Ohio—a well-known “Peace Democrat.”

On Election Day—November 8, 1864—Lincoln and McClellan each needed 117 electoral votes (out of a possible 233) to win the presidency. For much of the 1864 campaign season, Lincoln downplayed his chances of reelection and McClellan assumed that large numbers of Union soldiers would grant him support. However, thanks in great part to William Sherman’s capture of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, and overwhelming support from Union troops, Lincoln won the election easily. Additionally, Lincoln received support from more radical Republican factions and members of the Radical Democracy Party that demanded the end of slavery.

In the popular vote, Lincoln defeated McClellan, 55.1 percent to 44.9 percent. In the Electoral College, Lincoln’s victory was even more pronounced: 212 to 21. Lincoln won twenty-two states, and McClellan only carried three: New Jersey, Delaware, and Kentucky.36

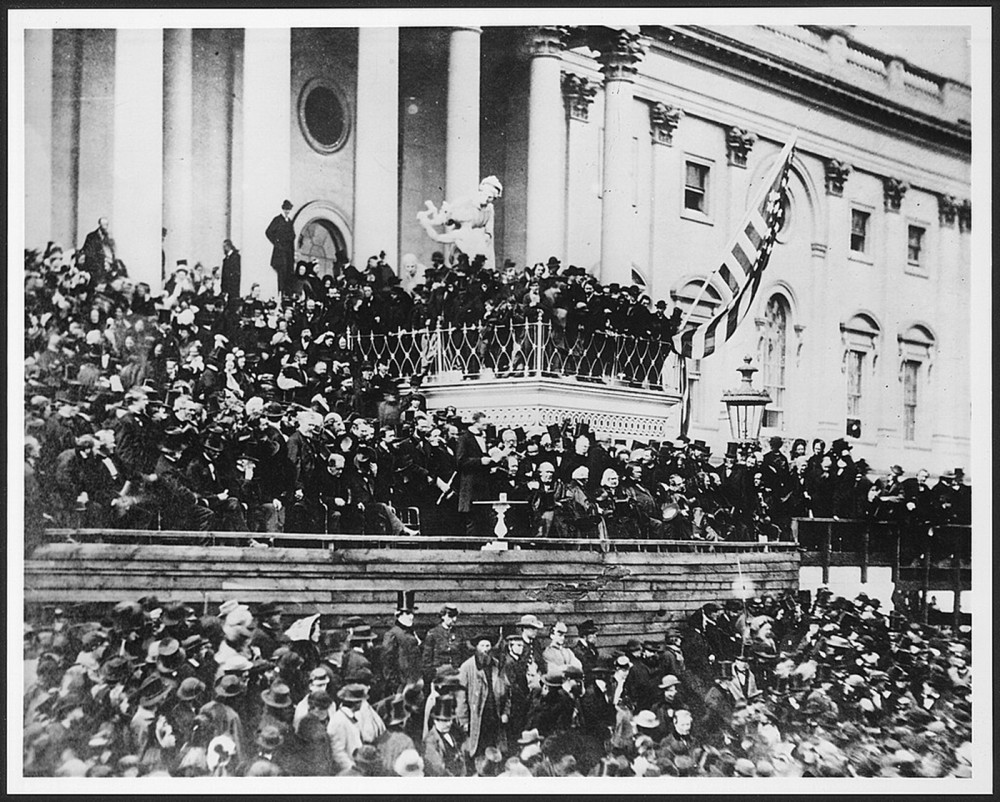

With crowds of people filling every inch of ground around the U.S. Capitol, President Lincoln delivered his inaugural address on March 4, 1865. Alexander Gardner, “Lincoln’s Second Inaugural,” between 1910 and 1920 from a photograph taken in 1865. Wikimedia.

In the wake of his reelection, Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address on March 4, 1865, in which he concluded:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.37

The years 1864 and 1865 were the very definition of hard war. Incredibly deadly for both sides, the Union campaigns in both the West and the East destroyed Confederate infrastructure and demonstrated the efficacy of the Union’s strategy. Following up on the successful capture of Atlanta, William Sherman conducted his March to the Sea in the fall of 1864, arriving in Savannah with time to capture it and deliver it as a Christmas present for Abraham Lincoln. Sherman’s path of destruction took on an even more destructive tone as he moved into the heart of the Confederacy in South Carolina in early 1865. The burning of Columbia, South Carolina, and subsequent capture of Charleston brought the hard hand of war to the birthplace of secession. With Grant’s dogged pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, effectively ending major Confederate military operations.

Unions soldiers pose in front of the Appomattox Court House after Lee’s surrender in April 1865. Wikimedia.

To ensure the permanent legal end of slavery, Republicans drafted the Thirteenth Amendment during the war. Yet the end of legal slavery did not mean the end of racial injustice. During the war, formerly enslaved people were often segregated into disease-ridden contraband camps. After the war, the Republican Reconstruction program of guaranteeing the rights of Black Americans succumbed to persistent racism and southern white violence. Long after 1865, most Black southerners continued to labor on plantations, albeit as nominally free tenants or sharecroppers, while facing public segregation and voting discrimination. The effects of slavery endured long after emancipation.

V. Conclusion

As battlefields fell silent in 1865, the question of secession had been answered, slavery had been eradicated, and America was once again territorially united. But in many ways, the conclusion of the Civil War created more questions than answers. How would the nation become one again? Who was responsible for rebuilding the South? What role would African Americans occupy in this society? Northern and southern soldiers returned home with broken bodies, broken spirits, and broken minds. Plantation owners had land but not labor. Recently freed African Americans had their labor but no land. Formerly enslaved people faced a world of possibilities—legal marriage, family reunions, employment, and fresh starts—but also a racist world of bitterness, violence, and limited opportunity. The war may have been over, but the battles for the peace were just beginning.

VI. Primary Sources

1. Alexander Stephens on slavery and the Confederate constitution, 1861

Confederates had to quickly create not only a government but also a nation, including all of the cultural values required to foster patriotism. In this speech, Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy, proclaims that slavery and white supremacy were not only the cause for secession but also the “cornerstone” of the Confederate nation.

2. General Benjamin F. Butler reacts to self-emancipation, 1861

Self-emancipating people posed a dilemma for the Union military. Soldiers were forbidden to interfere with slavery or assist runaways, but many soldiers disobeyed the policy. In May 1861, General Benjamin F. Butler went over his superiors’ heads and began accepting freedom-seeking people who came to Fortress Monroe in Virginia. Butler reasoned that these people were “contraband of war,” and he had as much a right to seize them as he did to seize enemy horses or cannons. Later that summer Congress affirmed Butler’s policy in the First Confiscation Act.

3. William Henry Singleton, a formerly enslaved man, recalls fighting for the Union, 1922

William Henry Singleton was born to his enslaved mother, Lettice, and her enslaver’s brother, William Singleton. At the age of four, he was sold away from his mother but ran back to her several times throughout his life. When the war broke out, he escaped to Union lines and volunteered for service. After being dismissed, he rallied one thousand Black soldiers and received a promotion as a sergeant.

4. Poem about Civil War nurses, 1866

The massive casualty rates of the Civil War meant that nurses were always needed. Women, North and South, left the comforts of home to care for the wounded. Hospital conditions were often so bad that many volunteer nurses quit soon after beginning. After the war, Kate Cumming, a nurse who traveled with the Army of Tennessee, published an account of her experience. She included a poem, written by an unknown author about nursing in the war.

5. Ambrose Bierce recalls his experience at the Battle of Shiloh, 1881

Civil War soldiers described the experience of combat as both terrifying and confusing. The American writer, Ambrose Bierce, captures both the confusion and terror of the Battle of Shiloh in the below excerpt of his 1881 recollections of the battle.

Music played an important role in the Civil War. Songs celebrated the cause, mourned the loss of life, and bound sings together in shared commitments to mutual sacrifice. These two songs, both written by women, one in the North and the other in the South, show the flexibility of Civil War music. The first is an example of the somber, sacralizing function of music, while the latter is an example of a lighthearted attempt at humor.

7. Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address, 1865

Abraham Lincoln offered a first draft of history in his second inaugural address, casting the Civil War as a war for union that later became a spiritual process of national penance for two hundred and fifty years of slaveholding. Lincoln also looked to the future, envisioning a harmonious and speedy Reconstruction that would take place “with malice toward none” and “with charity for all.”

8. Civil War nurses illustration, 1864

The Civil War ultimately opened a variety of arenas for Union and Confederate women’s participation. In the North, the United States Sanitary Commission in particular centralized women’s opportunities to volunteer as nurses, donate supplies, and to raise funds at Sanitary Fairs. This 1864 image from popular periodical Harper’s Weekly celebrates women’s contributions on the battlefield, in the hospital, in the parlor, and at the fair.

9. Burying the dead photograph, 1865

Death pervaded every aspect of life during the years of the Civil War. This gruesome photograph, taken after the battle of Cold Harbor, shows the hasty burial procedures used to reckon with unprecedented death. Dirty jobs like this were often left to Black soldiers or freedpeople in Contraband Camps.

VII. Reference Material

This chapter was edited by Angela Esco Elder and David Thomson, with content contributions by Thomas Balcerski, William Black, Frank Cirillo, Matthew C. Hulbert, Andrew F. Lang, John Patrick Riley, Angela Riotto, Gregory N. Stern, David Thomson, Ann Tucker, and Rebecca Zimmer.

Recommended citation: Thomas Balcerski et al., “The Civil War,” Angela Esco Elder and David Thomson, eds., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Ayers, Edward L. In the Presence of Mine Enemies: War in the Heart of America, 1859–1863. New York: Norton, 2003.

- Berry, Stephen, ed. Weirding the War: Stories from the Civil War’s Ragged Edges. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

- Blight, David. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Brasher, Glenn David. The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

- Clinton, Catherine, and Nina Silber, eds. Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Devine, Shauna. Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

- Fahs, Alice. The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North and South, 1861–1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York: Knopf, 2008.

- Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: Norton, 2011.

- Gannon, Barbara A. The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

- Grimsley, Mark. The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Towards Southern Civilians, 1861–1865. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Hess, Earl. The Union Soldier in Battle: Enduring the Ordeal of Combat. Lawrenceville: University Press of Kansas, 1997.

- Hulbert, Matthew C. The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory: How Civil War Bushwhackers Became Gunslingers in the American West. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016.

- Janney, Caroline E. Remembering The Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Jones, Howard. Blue and Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Lang, Andrew F. In the Wake of War: Military Occupation, Emancipation, and Civil War America. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2017.

- Manning, Chandra. What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War. New York: Knopf, 2007.

- McCurry, Stephanie. Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- McPherson, James. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Meier, Kathryn Shively. Nature’s Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Nelson, Megan Kate. Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012.

- Rable, George C. God’s Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

- Richardson, Heather Cox. The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies During the Civil War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Vorenberg, Michael. The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Whites, LeeAnn. The Civil War as a Crisis in Gender: Augusta, Georgia, 1860–1890. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000.

Notes

- This most recent estimation of 750,000 wartime deaths was put forward by J. David Hacker, “A Census-Based Account of the Civil War Dead,” Civil War History 57, no. 4 (December 2011): 306–347. [↩]

- Proceedings of the Conventions at Charleston and Baltimore: Published by Order of the National Democratic Convention (Washington, DC: n.p., 1860). [↩]

- William J. Cooper, We Have the War upon Us: The Onset of the Civil War, November 1860–April 1861 (New York: Knopf, 2012), 14. [↩]

- “A Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union,” January 9, 1861, Avalon Project at the Yale Law School. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_scarsec.asp, accessed August 1, 2015. [↩]

- Alexander Stephens, speech in Savannah, Georgia, delivered March 21, 1861, quoted in Henry Cleveland, Alexander Stephens, in Public and Private. With Letters and Speeches Before, During and Since the War (Philadelphia: National, 1866), 719. [↩]

- “Declaration of the Immediate Causes”. [↩]

- See Jon L. Wakelyn, ed., Southern Unionist Pamphlets and the Civil War (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999). [↩]

- Steven Hahn, The Political Worlds of Slavery and Freedom (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 55–114. [↩]

- Horace Greeley, The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States of America, 1860–1864, Volume 1 (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood, 1864), 366–367. [↩]

- Abraham Lincoln, “Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [↩]

- Abraham Lincoln to Orville Browning, September 22, 1861, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [↩]

- Thomas H. O’Connor, Civil War Boston: Home Front and Battlefield (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997), 67. [↩]

- Excerpt from Benj. F. Butler to Lieutenant Genl. Scott, 27 May 1861, B-99 1861, Letters Received Irregular, Secretary of War, Record Group 107, National Archives. http://www.freedmen.umd.edu/Butler.html. [↩]

- “THE SLAVE QUESTION.; Letter from Major-Gen. Butler on the Treatment of Fugitive Slaves,” New York Times (August 6, 1861). [↩]

- Heather Cox Richardson, The Greatest Nation of the Earth: Republican Economic Policies During the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997). [↩]

- For literacy rates within the armies, see Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1952), 304–306; and Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1943), 335–337. [↩]

- For more on music in the Civil War, see Christian McWhirter, Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012). [↩]

- Ethan S. Rafuse, McClellan’s War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005). [↩]

- Steven E. Woodworth, ed., The Shiloh Campaign (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009). [↩]

- Glenn David Brasher, The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012). [↩]

- Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863, Presidential Proclamations, 1791–1991, Record Group 11, General Records of the United States Government, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [↩]

- Abraham Lincoln to Ulysses S. Grant, August 9, 1863, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [↩]

- James Henry Gooding to Abraham Lincoln, September 28, 1863, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. [↩]

- James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 862. [↩]

- Quoted in Allen Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004), 247. [↩]

- See Eugene C. Murdock, One Million Men: The Civil War Draft in the North (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1971). [↩]

- Laura Edwards, Scarlett Doesn’t Live Here Anymore: Southern Women in the Civil War Era (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 85. [↩]

- Quoted in Heidi Schoof, Elizabeth Van Lew: Civil War Spy (Minneapolis, MN: Compass Books, 2006), 85. [↩]

- Shauna Devine, Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 70–71. [↩]

- . Emma Edwards, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: Comprising the Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps, and Battle-Fields (Hartford, CT: Williams, 1865), 6. [↩]

- C. Vann Woodward, ed., Mary Chesnut’s Civil War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981), 85. [↩]

- Ibid., 158. [↩]

- Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Knopf, 2008). [↩]

- Sally Randle Perry, November 30, 1867, Sally Randle Perry Diary, 1867–1868, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama. [↩]

- LeeAnn Whites, The Civil War as a Crisis in Gender: Augusta, Georgia, 1860–1890 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000), 93–95. [↩]

- Presidential Elections, 1789–2008 (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2010), 135, 225. [↩]

- Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address; endorsed by Lincoln, April 10, 1865, March 4, 1865, General Correspondence, 1837–1897, The Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Washington, D.C. [↩]