23. The Great Depression

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

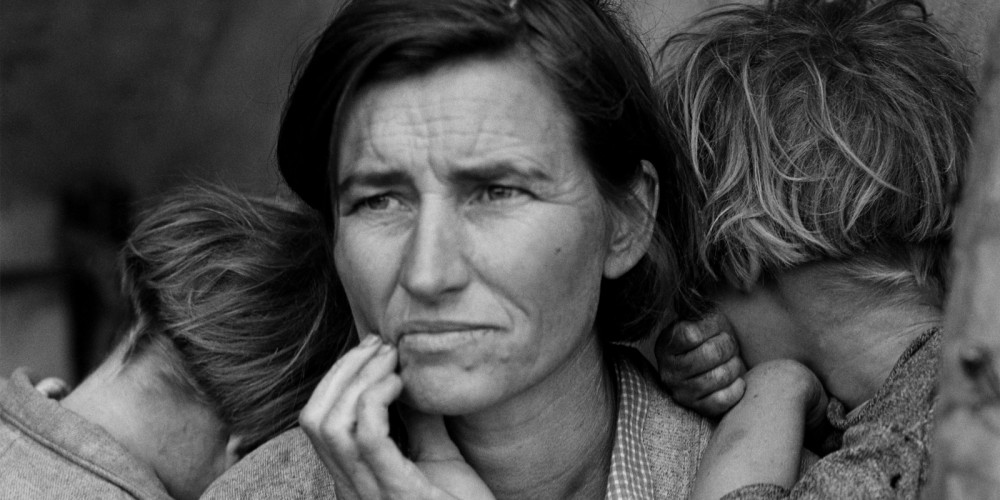

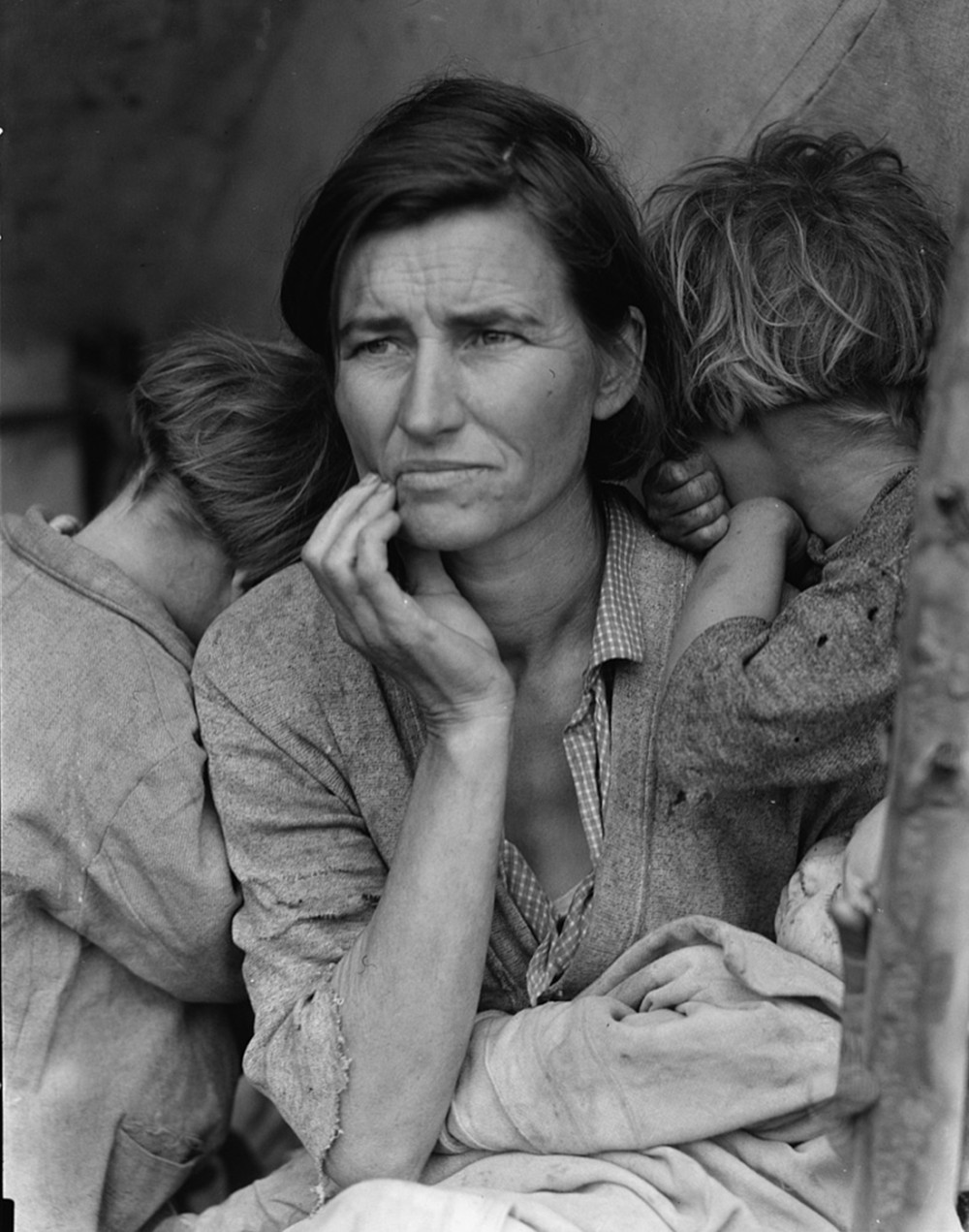

“Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California.” Dorothea Lange, Farm Security Administration. 1936. Via Library of Congress.

“Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California.” Dorothea Lange, Farm Security Administration. 1936. Via Library of Congress.

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The wonder of the stock market permeated popular culture in the 1920s. Although it was released during the first year of the Great Depression, the 1930 film High Society Blues captured the speculative hope and prosperity of the previous decade. “I’m in the Market for You,” a popular musical number from the film, even used the stock market as a metaphor for love: You’re going up, up, up in my estimation, / I want a thousand shares of your caresses, too. / We’ll count the hugs and kisses, / When dividends are due, / Cause I’m in the market for you. But, just as the song was being recorded in 1929, the stock market reached the apex of its swift climb, crashed, and brought an abrupt end to the seeming prosperity of the “Roaring ‘20s.” The Great Depression had arrived.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

II. The Origins of the Great Depression

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0

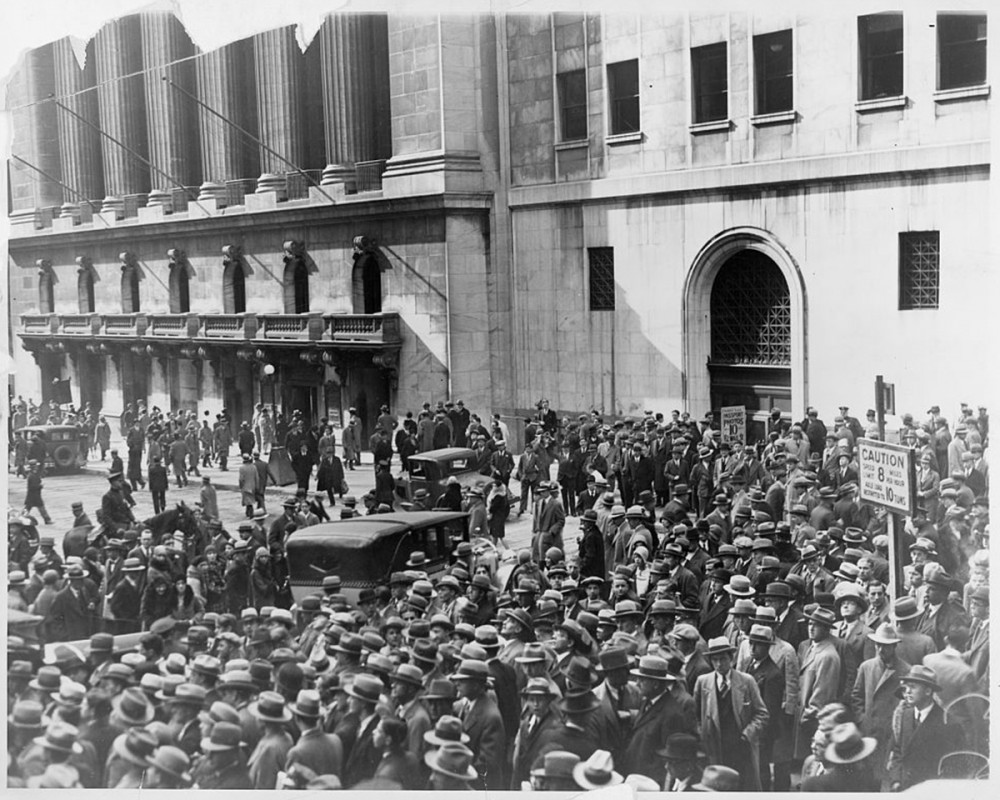

“Crowd of people gather outside the New York Stock Exchange following the Crash of 1929,” 1929. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99471695/.

“Crowd of people gather outside the New York Stock Exchange following the Crash of 1929,” 1929. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99471695/.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 5 On Thursday, October 24, 1929, stock market prices suddenly plummeted. Ten billion dollars in investments (roughly equivalent to about $100 billion today) disappeared in a matter of hours. Panicked selling set in, stock sunk to record lows, and stunned investors crowded the New York Stock Exchange demanding answers. Leading bankers met privately at the offices of J.P. Morgan and raised millions in personal and institutional contributions to halt the slide. They marched across the street and ceremoniously bought stocks at inflated prices. The market temporarily stabilized but fears spread over the weekend and the following week frightened investors dumped their portfolios to avoid further losses. On October 29, “Black Tuesday,” the stock market began its long precipitous fall. Stock values evaporated. Shares of U.S. Steel dropped from $262 to $22. General Motors’ stock fell from $73 a share to $8. Four-fifths of the J.D. Rockefeller’s fortune—the greatest in American history—vanished.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Although the Crash stunned the nation, it exposed the deeper, underlying problems with the American economy in the 1920s. The stock market’s popularity grew throughout the decade, but only 2.5% of Americans had brokerage accounts; the overwhelming majority of Americans had no direct personal stake in Wall Street. The stock market’s collapse, no matter how dramatic, did not by itself depress the American economy. Instead, the Crash exposed a great number of factors which, when combined with the financial panic, sunk the American economy into the greatest of all economic crises. Rising inequality, declining demand, rural collapse, overextended investors, and the bursting of speculative bubbles all conspired to plunge the nation into the Great Depression.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 Despite resistance by Progressives, the vast gap between rich and poor accelerated throughout the early-twentieth century. In the aggregate, Americans were better off in 1929 than in 1920. Per capita income had risen 10% for all Americans, but 75% for the nation’s wealthiest citizens. ((George Donelson Moss, The Rise of Modern America: A History of the American People, 1890-1945 (New York: Prentice Hall, 1995), 185-86.)) The return of conservative politics in the 1920s reinforced federal fiscal policies that exacerbated the divide: low corporate and personal taxes, easy credit, and depressed interest rates overwhelmingly favored wealthy investors who, flush with cash, spent their money on luxury goods and speculative investments in the rapidly rising stock market.

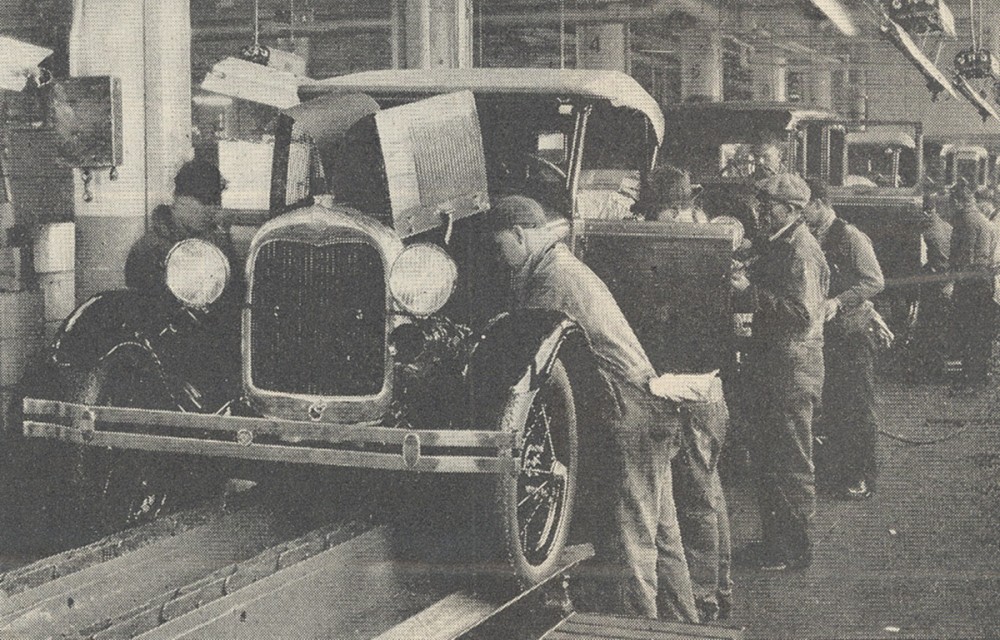

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 The pro-business policies of the 1920s were designed for an American economy built upon the production and consumption of durable goods. Yet, by the late 1920s, much of the market was saturated. The boom of automobile manufacturing, the great driver of the American economy in the 1920s, slowed as fewer and fewer Americans with the means to purchase a car had not already done so. More and more, the well-to-do had no need for the new automobiles, radios, and other consumer goods that fueled GDP growth in the 1920s. When products failed to sell, inventories piled up, manufacturers scaled back production, and companies fired workers, stripping potential consumers of cash, blunting demand for consumer goods, and replicating the downward economic cycle. The situation was only compounded by increased automation and rising efficiency in American factories. Despite impressive overall growth throughout the 1920s, unemployment hovered around 7% throughout the decade, suppressing purchasing power for a great swath of potential consumers. ((Ibid., 186.))

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

While a manufacturing innovation, Henry Ford’s assembly line produced so many cars as to flood the automobile market in the 1920s. Interview with Henry Ford, Literary Digest, January 7, 1928. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ford_Motor_Company_assembly_line.jpg.

While a manufacturing innovation, Henry Ford’s assembly line produced so many cars as to flood the automobile market in the 1920s. Interview with Henry Ford, Literary Digest, January 7, 1928. Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ford_Motor_Company_assembly_line.jpg.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 For American farmers, meanwhile, “hard times” began long before the markets crashed. In 1920 and 1921, after several years of larger-than-average profits, farm prices in the South and West continued their long decline, plummeting as production climbed and domestic and international demand for cotton, foodstuffs, and other agricultural products stalled. Widespread soil exhaustion on western farms only compounded the problem. Farmers found themselves unable to make payments on loans taken out during the good years, and banks in agricultural areas tightened credit in response. By 1929, farm families were overextended, in no shape to make up for declining consumption, and in a precarious economic position even before the Depression wrecked the global economy. ((Robert S. McElvaine, The Great Depression: America, 1921-1940 (New York: Random House, 1984), 36.))

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 Despite serious foundational problems in the industrial and agricultural economy, most Americans in 1929 and 1930 still believed the economy would bounce back. In 1930, amid one of the Depression’s many false hopes, President Herbert Hoover reassured an audience that “the depression is over.” ((John Steel Gordon, An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power (Harper Perennial), 320.)) But the president was not simply guilty of false optimism. Hoover made many mistakes. During his 1928 election campaign, Hoover promoted higher tariffs as a means for encouraging domestic consumption and protecting American farmers from foreign competition. Spurred by the ongoing agricultural depression, Hoover signed into law the highest tariff in American history, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, just as global markets began to crumble. Other countries responded in kind, tariff walls rose across the globe, and international trade ground to a halt. Between 1929 and 1932, international trade dropped from $36 billion to only $12 billion. American exports fell by 78%. Combined with overproduction and declining domestic consumption, the tariff exacerbated the world’s economic collapse. ((Moss, 186-87.))

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 But beyond structural flaws, speculative bubbles, and destructive protectionism, the final contributing element of the Great Depression was a quintessentially human one: panic. The frantic reaction to the market’s fall aggravated the economy’s other many failings. More economic policies backfired. The Federal Reserve over-corrected in their response to speculation by raising interest rates and tightening credit. Across the country, banks denied loans and called in debts. Their patrons, afraid that reactionary policies meant further financial trouble, rushed to withdraw money before institutions could close their doors, ensuring their fate. Such bank runs were not uncommon in the 1920s, but, in 1930, with the economy worsening and panic from the crash accelerating, 1,352 banks failed. In 1932, nearly 2,300 banks collapsed, taking personal deposits, savings, and credit with them. ((David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 65, 68.))

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 The Great Depression was the confluence of many problems, most of which had begun during a time of unprecedented economic growth. Fiscal policies of the Republican “business presidents” undoubtedly widened the gap between rich and poor and fostered a “stand-off” over international trade, but such policies were widely popular and, for much of the decade, widely seen as a source of the decade’s explosive growth. With fortunes to be won and standards of living to maintain, few Americans had the foresight or wherewithal to repudiate an age of easy credit, rampant consumerism, and wild speculation. Instead, as the Depression worked its way across the United States, Americans hoped to weather the economic storm as best they could, waiting for some form of relief, any answer to the ever-mounting economic collapse that strangled so many Americans’ lives.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

III. Herbert Hoover and the Politics of the Depression

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0

“Unemployed men queued outside a depression soup kitchen opened in Chicago by Al Capone,” February 1931. Wikimeida.

“Unemployed men queued outside a depression soup kitchen opened in Chicago by Al Capone,” February 1931. Wikimeida.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 As the Depression spread, public blame settled on President Herbert Hoover and the conservative politics of the Republican Party. But Hoover was as much victim as perpetrator, a man who had the misfortune of becoming a visible symbol for large invisible forces. In 1928 Hoover had no reason to believe that his presidency would be any different than that of his predecessor, Calvin Coolidge, whose time in office was marked by relative government inaction, seemingly rampant prosperity, and high approval ratings.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Coolidge had decided not to seek a second term in 1928. A man of few words, “Silent Cal” publicized this decision by handing a scrap of paper to a reporter that simply read: “I do not choose to run for president in 1928.” The race therefore became a contest between the Democratic governor of New York, Al Smith, whose Catholic faith and immigrant background aroused nativist suspicions and whose connections to Tammany Hall and anti-Prohibition politics offended reformers, and the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover, whose All-American, Midwestern, Protestant background and managerial prowess during the First World War endeared him to American voters. ((Allan J. Lichtman, Prejudice and the Old Politics: The Presidential Election of 1928 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1979).))

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Hoover epitomized the “self-made man.” Orphaned at age 9, he was raised by a strict Quaker uncle on the West Coast. He graduated from Stanford University in 1895 and worked as an engineer for several multinational mining companies. He became a household name during World War I when he oversaw voluntary rationing as the head of the U.S. Food Administration and, after the armistice, served as the Director General of the American Relief Association in Europe. Hoover’s reputation for humanitarian service and problem-solving translated into popular support, even as the public soured on Wilson’s Progressive activism. Hoover was one of the few politicians whose career benefitted from wartime public service. After the war both the Democratic and Republican parties tried to draft him to run for president in 1920. ((Richard Norton Smith, An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987).))

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Hoover declined to run in 1920 and 1924. He served instead as Secretary of Commerce under both Harding and Coolidge, taking an active role in all aspects of government. In 1928, he seemed the natural successor to Coolidge. Politically, aside from the issue of Prohibition (he was a “dry,” Smith a “wet”), Hoover’s platform differed very little from Smith’s, leaving little to discuss during the campaign except personality and religion. Both benefitted Hoover. Smith’s background engendered opposition from otherwise solid Democratic states, especially in the South, where his Catholic, ethnic, urban, and anti-Prohibition background were anathema. His popularity among urban ethnic voters counted for little. Several southern states, in part owing to the work of itinerant evangelical politicking, voted Republican for the first time since Reconstruction. Hoover won in a landslide, taking nearly 60% of the popular vote. ((Ibid.))

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Although Hoover is sometimes categorized as a “business president” in line with his Republican predecessors, he also embraced an inherent business progressivism, a system of voluntary action called “Associationalism” that assumed Americans could maintain a web of voluntary cooperative organizations dedicated to providing economic assistance and services to those in need. Businesses, the thinking went, would willingly limit harmful practice for the greater economic good. To Hoover, direct government aid would discourage a healthy work ethic while Associationalism would encourage the very self-control and self-initiative that fueled economic growth. But when the Depression exposed the incapacity of such strategies to produce an economic recovery, Hoover proved insufficiently flexible to recognize the limits of his ideology. And when the ideology failed, so too did his presidency. ((Kennedy, 70-103.))

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 Hoover entered office upon a wave of popular support, but by October 1929 the economic collapse had overwhelmed his presidency. Like all too many Americans, Hoover and his advisers assumed—or perhaps simply hoped—that the sharp financial and economic decline was a temporary downturn, another “bust” of the inevitable boom-bust cycles that stretched back through America’s commercial history. Many economists argued that periodic busts culled weak firms and paved the way for future growth. And so when suffering Americans looked to Hoover for help, Hoover could only answer with volunteerism. He asked business leaders to promise to maintain investments and employment and encouraged state and local charities to provide assistance to those in need. Hoover established the President’s Organization for Unemployment Relief, or POUR, to help organize the efforts of private agencies. While POUR urged charitable giving, charitable relief organizations were overwhelmed by the growing needs of the many multiplying unemployed, underfed, and unhoused Americans. By mid-1932, for instance, a quarter of all of New York’s private charities closed: they had simply run out of money. In Atlanta, solvent relief charities could only provide $1.30 per week to needy families. The size and scope of the Depression overpowered the radically insufficient capacity of private volunteer organizations to mediate the crisis. ((Ibid.))

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 By 1932, with the economy long-since stagnant and a reelection campaign looming, Hoover, hoping to stimulate American industry, created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide emergency loans to banks, building-and-loan societies, railroads, and other private industries. It was radical in its use of direct government aid and out of character for the normally laissez-faire Hoover, but it also bypassed needy Americans to bolster industrial and financial interests. New York Congressman Fiorello LaGuardia, who later served as mayor of New York City, captured public sentiment when he denounced the RFC as a “millionaire’s dole.” ((Ibid., 76.))

IV. The Bonus Army

¶ 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

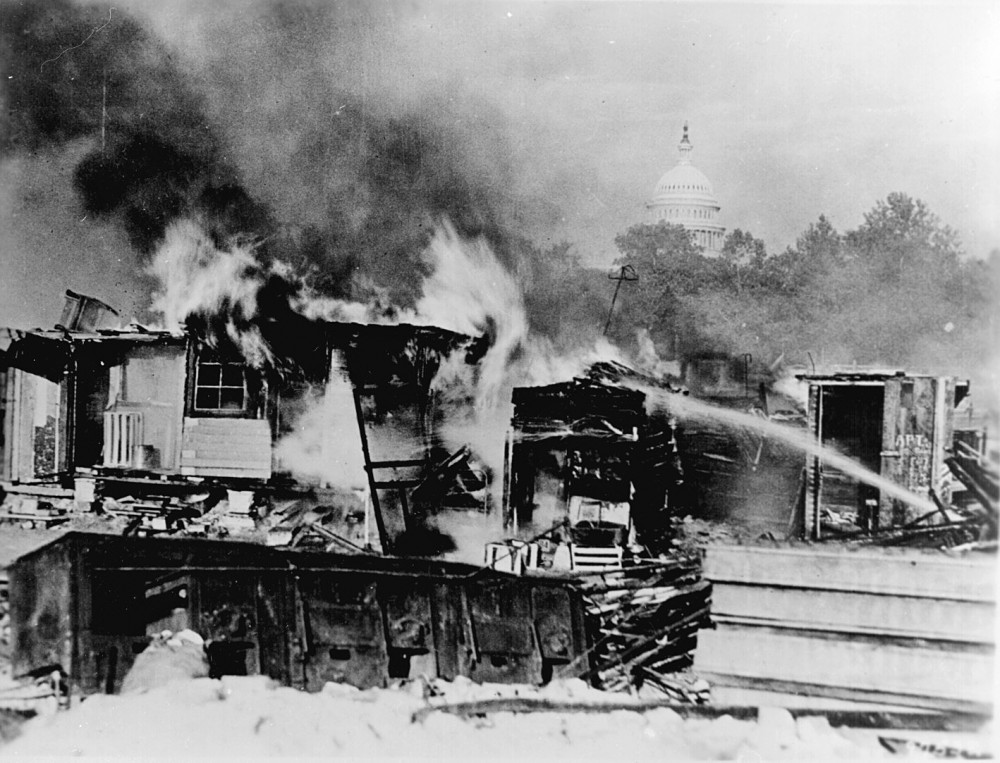

“Shacks, put up by the Bonus Army on the Anacostia flats, Washington, D.C., burning after the battle with the military. The Capitol in the background. 1932.” Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Evictbonusarmy.jpg.

“Shacks, put up by the Bonus Army on the Anacostia flats, Washington, D.C., burning after the battle with the military. The Capitol in the background. 1932.” Wikimedia, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Evictbonusarmy.jpg.

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 Hoover’s reaction to a major public protest sealed his legacy. In the summer of 1932, Congress debated a bill authorizing immediate payment of long-promised cash bonuses to veterans of World War I, originally scheduled to be paid out in 1945. Given the economic hardships facing the country, the bonus came to symbolize government relief for the most deserving recipients, and from across the country more than 15,000 unemployed veterans and their families converged on Washington, D.C. They erected a tent city across the Potomac River in Anacostia Flats, a “Hooverville” in the spirit of the camps of homeless and unemployed Americans then appearing in American cities.

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 Concerned with what immediate payment would do to the federal budget, Hoover opposed the bill, which was eventually voted down by the Senate. While most of the “Bonus Army” left Washington in defeat, many stayed to press their case. Hoover called the remaining veterans “insurrectionists” and ordered them to leave. When thousands failed to heed the vacation order, General Douglas MacArthur, accompanied by local police, infantry, cavalry, tanks, and a machine gun squadron, stormed the tent city and routed the Bonus Army. National media covered the disaster as troops chased down men and women, tear-gassed children, and torched the shantytown. ((Kennedy, 92.))

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 Hoover’s insensitivity toward suffering Americans, his unwillingness to address widespread economic problems, and his repeated platitudes about returning prosperity condemned his presidency. Hoover of course was not responsible for the Depression, not personally. But neither he nor his advisers conceived of the enormity of the crisis, a crisis his conservative ideology could neither accommodate nor address. As a result, Americans found little relief from Washington. They were on their own.

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

V. The Lived Experience of the Great Depression

¶ 29

Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0

“Hooverville, Seattle.” 1932-1937. Washington State Archives. http://www.digitalarchives.wa.gov/Record/View/B7A94A0DC95F7B3E0F1081FDB3A72C1E

“Hooverville, Seattle.” 1932-1937. Washington State Archives. http://www.digitalarchives.wa.gov/Record/View/B7A94A0DC95F7B3E0F1081FDB3A72C1E

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 In 1934 a woman from Humboldt County, California, wrote to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt seeking a job for her husband, a surveyor, who had been out of work for nearly two years. The pair had survived on the meager income she received from working at the county courthouse. “My salary could keep us going,” she explained, “but—I am to have a baby.” The family needed temporary help, and, she explained, “after that I can go back to work and we can work out our own salvation. But to have this baby come to a home full of worry and despair, with no money for the things it needs, is not fair. It needs and deserves a happy start in life.” ((Mrs. M. H. A. to Eleanor Roosevelt, June 14, 1934, in Robert S. McElvaine, ed., Down and Out in the Great Depression: Letters from the Forgotten Man (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983), 54–55.))

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0 As the United States slid ever deeper into the Great Depression, such tragic scenes played out time and time again. Individuals, families, and communities faced the painful, frightening, and often bewildering collapse of the economic institutions upon which they depended. The more fortunate were spared worst effects, and a few even profited from it, but by the end of 1932, the crisis had become so deep and so widespread that most Americans had suffered directly. Markets crashed through no fault of their own. Workers were plunged into poverty because of impersonal forces for which they shared no responsibility. With no safety net, they were thrown into economic chaos.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 With rampant unemployment and declining wages, Americans slashed expenses. The fortunate could survive by simply deferring vacations and regular consumer purchases. Middle- and working-class Americans might rely upon disappearing credit at neighborhood stores, default on utility bills, or skip meals. Those that could borrowed from relatives or took in boarders in homes or “doubled up” in tenements. The most desperate, the chronically unemployed, encamped on public or marginal lands in “Hoovervilles,” spontaneous shantytowns that dotted America’s cities, depending upon breadlines and street-corner peddling. Poor women and young children entered the labor force, as they always had. The ideal of the “male breadwinner” was always a fiction for poor Americans, but the Depression decimated millions of new workers. The emotional and psychological shocks of unemployment and underemployment only added to the shocking material depravities of the Depression. Social workers and charity officials, for instance, often found the unemployed suffering from feelings of futility, anger, bitterness, confusion, and loss of pride. Such feelings affected the rural poor no less than the urban. ((See especially chapter five of Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990).))

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0

VI. Migration and the Great Depression

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 On the Great Plains, environmental catastrophe deepened America’s longstanding agricultural crisis and magnified the tragedy of the Depression. Beginning in 1932, severe droughts hit from Texas to the Dakotas and lasted until at least 1936. The droughts compounded years of agricultural mismanagement. To grow their crops, Plains farmers had plowed up natural ground cover that had taken ages to form over the surface of the dry Plains states. Relatively wet decades had protected them, but, during the early 1930s, without rain, the exposed fertile topsoil turned to dust, and without sod or windbreaks such as trees, rolling winds churned the dust into massive storms that blotted out the sky, choked settlers and livestock, and rained dirt not only across the region but as far east as Washington, D.C., New England, and ships on the Atlantic Ocean. The “Dust Bowl,” as the region became known, exposed all-too-late the need for conservation. The region’s farmers, already hit by years of foreclosures and declining commodity prices, were decimated. ((Robert S. McElvaine, ed., Encyclopedia of the Great Depression (New York: Macmillan, 2004), 320.)) For many in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas who were “baked out, blown out, and broke,” their only hope was to travel west to California, whose rains still brought bountiful harvests and–potentially–jobs for farmworkers. It was an exodus. Oklahoma lost 440,000 people, or a full 18.4 percent of its 1930 population, to out-migration. ((Donald Worster, Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 48.))

¶ 35

Leave a comment on paragraph 35 1

This iconic photograph made real the suffering of millions during the Great Depression. Dorothea Lange, “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California” or “Migrant Mother,” February/March 1936. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1998021539/PP/.

This iconic photograph made real the suffering of millions during the Great Depression. Dorothea Lange, “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California” or “Migrant Mother,” February/March 1936. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1998021539/PP/.

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 2 Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother became one of the most enduring images of the “Dust Bowl” and the ensuing westward exodus. Lange, a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, captured the image at migrant farmworker camp in Nipomo, California, in 1936. In the photograph a young mother stares out with a worried, weary expression. She was a migrant, having left her home in Oklahoma to follow the crops to the Golden State. She took part in what many in the mid-1930s were beginning to recognize as a vast migration of families out of the southwestern plains states. In the image she cradles an infant and supports two older children, who cling to her. Lange’s photo encapsulated the nation’s struggle. The subject of the photograph seemed used to hard work but down on her luck, and uncertain about what the future might hold.

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 2 The “Okies,” as such westward migrants were disparagingly called by their new neighbors, were the most visible group many who were on the move during the Depression, lured by news and rumors of jobs in far flung regions of the country. By 1932 sociologists were estimating that millions of men were on the roads and rails travelling the country. Economists sought to quantify the movement of families from the Plains. Popular magazines and newspapers were filled with stories of homeless boys and the veterans-turned-migrants of the Bonus Army commandeering boxcars. Popular culture, such as William Wellman’s 1933 film, Wild Boys of the Road, and, most famously, John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939 and turned into a hit movie a year later, captured the Depression’s dislocated populations.

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 These years witnessed the first significant reversal in the flow of people between rural and urban areas. Thousands of city-dwellers fled the jobless cities and moved to the country looking for work. As relief efforts floundered, many state and local officials threw up barriers to migration, making it difficult for newcomers to receive relief or find work. Some state legislatures made it a crime to bring poor migrants into the state and allowed local officials to deport migrants to neighboring states. In the winter of 1935-1936, California, Florida, and Colorado established “border blockades” to block poor migrants from their states and reduce competition with local residents for jobs. A billboard outside Tulsa, Oklahoma, informed potential migrants that there were “NO JOBS in California” and warned them to “KEEP Out.” ((James N. Gregory, American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 22.))

¶ 39

Leave a comment on paragraph 39 1

During her assignment as a photographer for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Dorothea Lange documented the movement of migrant families forced from their homes by drought and economic depression. This family was in the process of traveling 124 miles by foot, across Oklahoma, because the father was unable to receive relief or WPA work of his own due to an illness. Dorothea Lange, “Family walking on highway, five children” (June 1938) Works Progress Administration, Library of Congress.

During her assignment as a photographer for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Dorothea Lange documented the movement of migrant families forced from their homes by drought and economic depression. This family was in the process of traveling 124 miles by foot, across Oklahoma, because the father was unable to receive relief or WPA work of his own due to an illness. Dorothea Lange, “Family walking on highway, five children” (June 1938) Works Progress Administration, Library of Congress.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 Sympathy for migrants, however, accelerated late in the Depression with the publication of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. The Joad family’s struggles drew attention to the plight of Depression-era migrants and, just a month after the nationwide release of the film version, Congress created the Select Committee to Investigate the Interstate Migration of Destitute Citizens. Starting in 1940, the Committee held widely publicized hearings. But it was too late. Within a year of its founding, defense industries were already gearing up in the wake of the outbreak of World War II, and the “problem” of migration suddenly became a lack of migrants needed to fill war industries. Such relief was nowhere to be found in the 1930s.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 Americans meanwhile feared foreign workers willing to work for even lower wages. The Saturday Evening Post warned that foreign immigrants, who were “compelled to accept employment on any terms and conditions offered,” would exacerbate the economic crisis. ((Cybelle Fox, Three Worlds of Relief (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 126.)) On September 8, 1930, the Hoover administration issued a press release on the administration of immigration laws “under existing conditions of unemployment.” Hoover instructed consular officers to scrutinize carefully the visa applications of those “likely to become public charges” and suggested that this might include denying visas to most, if not all, alien laborers and artisans. The crisis itself had served to stifle foreign immigration, but such restrictive and exclusionary actions in the first years of the Depression intensified its effects. The number of European visas issued fell roughly 60 percent while deportations dramatically increased. Between 1930 and 1932, 54,000 people were deported. An additional 44,000 deportable aliens left “voluntarily.” ((Fox, Three Worlds of Relief, 127.))

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 Exclusionary measures hit Mexican immigrants particularly hard. The State Department made a concerted effort to reduce immigration from Mexico as early as 1929 and Hoover’s executive actions arrived the following year. Officials in the Southwest led a coordinated effort to push out Mexican immigrants. In Los Angeles, the Citizens Committee on Coordination of Unemployment Relief began working closely with federal officials in early 1931 to conduct deportation raids while the Los Angeles County Department of Charities began a simultaneous drive to repatriate Mexicans and Mexican Americans on relief, negotiating a charity rate with the railroads to return Mexicans “voluntarily” to their mother country. According to the federal census, from 1930 to 1940 the Mexican-born population living in Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas fell from 616,998 to 377,433. Franklin Roosevelt did not indulge anti-immigrant sentiment as willingly as Hoover had. Under the New Deal, the Immigration and Naturalization Service halted some of the Hoover Administration’s most divisive practices, but, with jobs suddenly scarce, hostile attitudes intensified, and official policies less than welcoming, immigration plummeted and deportations rose. Over the course of the Depression, more people left the United States than entered it. ((ristide Zolberg, A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America (New York: Russell Sage, 2006), 269.))

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0

VII. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the “First” New Deal

¶ 44

Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0

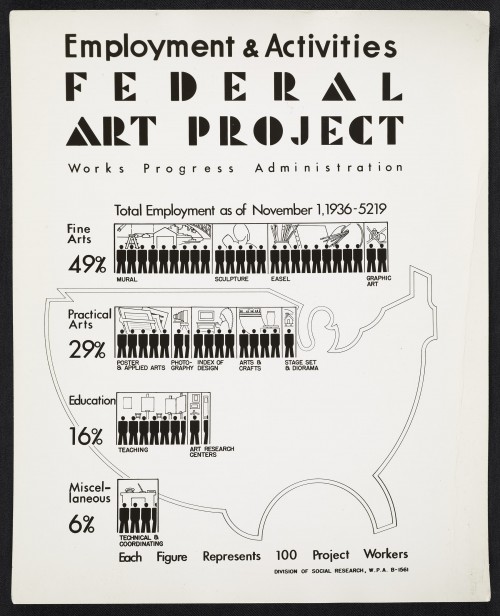

Posters like this showing the extent of the Federal Art Project were used to prove the worth of the WPA’s various endeavors and, by extension, the value of the New Deal to the American people. “Employment and Activities poster for the WPA’s Federal Art Project,” January 1, 1936. Wikimedia.

Posters like this showing the extent of the Federal Art Project were used to prove the worth of the WPA’s various endeavors and, by extension, the value of the New Deal to the American people. “Employment and Activities poster for the WPA’s Federal Art Project,” January 1, 1936. Wikimedia.

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 The early years of the Depression were catastrophic. The crisis, far from relenting, deepened each year. Unemployment peaked at 25% in 1932. With no end in sight, and with private firms crippled and charities overwhelmed by the crisis, Americans looked to their government as the last barrier against starvation, hopelessness, and perpetual poverty.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 Few presidential elections in modern American history have been more consequential than that of 1932. The United States was struggling through the third year of the Depression and exasperated voters overthrew Hoover in a landslide to elect the Democratic governor of New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt came from a privileged background in New York’s Hudson River Valley (his distant cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, became president while Franklin was at Harvard). Franklin Roosevelt embarked upon a slow but steady ascent through state and national politics. In 1913, he was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy, a position he held during the defense emergency of World War I. In the course of his rise, in the summer of 1921, Roosevelt suffered a sudden bout of lower-body pain and paralysis. He was diagnosed with polio. The disease left him a paraplegic, but, encouraged and assisted by his wife, Eleanor, Roosevelt sought therapeutic treatment and maintained sufficient political connections to reenter politics. In 1928, Roosevelt won election as governor of New York. He oversaw the rise of the Depression and drew from progressivism to address the economic crisis. During his gubernatorial tenure, Roosevelt introduced the first comprehensive unemployment relief program and helped to pioneer efforts to expand public utilities. He also relied on like-minded advisors. For example, Frances Perkins, then commissioner of the state’s Labor Department, successfully advocated pioneering legislation which enhanced workplace safety and reduced the use of child labor in factories. Perkins later accompanied Roosevelt to Washington and serve as the nation’s first female Secretary of Labor. ((Biographies of Roosevelt include Kenneth C. Davis, FDR: The Beckoning of Destiny: 1882-1928 (New York: Rand House, 1972); and Jean Edward Smith, FDR (New York: Random House, 2007).))

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 On July 1, 1932, Roosevelt, the newly-designated presidential nominee of the Democratic Party, delivered the first and one of the most famous on-site acceptance speeches in American presidential history. Building to a conclusion, he promised, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” Newspaper editors seized upon the phrase “new deal,” and it entered the American political lexicon as shorthand for Roosevelt’s program to address the Great Depression. ((Outstanding general treatments of the New Deal include: Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Age of Roosevelt, 3 vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1956–1960); William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (New York: Harper and Row, 1963); Anthony J. Badger, The New Deal: The Depression Years, 1933–1940 (New York: Hill and Wang), 1989; David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). On Roosevelt, see especially James MacGregor Burns, Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1956); Frank B. Friedel, Franklin D. Roosevelt, 4 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1952–1973); Patrick J. Maney, The Roosevelt Presence: A Biography of Franklin D. Roosevelt (New York: Twayne, 1992); Alan Brinkley, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).)) There were, however, few hints in his political campaign that suggested the size and scope of the “New Deal.” Regardless, Roosevelt crushed Hoover. He won more counties than any previous candidate in American history. He spent the months between his election and inauguration traveling, planning, and assembling a team of advisors, the famous “Brain Trust” of academics and experts, to help him formulate a plan of attack. On March 4th, 1933, in his first Inaugural Address, Roosevelt famously declared, “This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” ((Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1933. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=14473.))

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 Roosevelt’s reassuring words would have rung hollow if he had not taken swift action against the economic crisis. In his first days in office, Roosevelt and his advisers prepared, submitted, and secured Congressional enactment of numerous laws designed to arrest the worst of the Great Depression. His administration threw the federal government headlong into the fight against the Depression.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 Roosevelt immediately looked to stabilize the collapsing banking system. He declared a national “bank holiday” closing American banks and set to work pushing the Emergency Banking Act swiftly through Congress. On March 12th, the night before select banks reopened under stricter federal guidelines, Roosevelt appeared on the radio in the first of his “Fireside Chats.” The addresses, which the president continued delivering through four terms, were informal, even personal. Roosevelt used his airtime to explain New Deal legislation, to encourage confidence in government action, and to mobilize the American people’s support. In the first “chat,” Roosevelt described the new banking safeguards and asked the public to place their trust and their savings in banks. Americans responded and across the country, deposits outpaced withdrawals. The act was a major success. In June, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Banking Act, which instituted federal deposit insurance and barred the mixing of commercial and investment banking. ((Michael E. Parrish, Securities Regulation and the New Deal (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970).))

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 Stabilizing the banks was only a first step. In the remainder of his “First Hundred Days,” Roosevelt and his congressional allies focused especially on relief for suffering Americans. ((See especially Anthony J. Badger, FDR: The First Hundred Days (New York: Hill and Wang, 2008).)) Congress debated, amended, and passed what Roosevelt proposed. As one historian noted, the president “directed the entire operation like a seasoned field general.” ((William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (New York: Harper and Row, 1963).)) And despite some questions over the constitutionality of many of his actions, Americans and their congressional representatives conceded that the crisis demanded swift and immediate action. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employed young men on conservation and reforestation projects; the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) provided direct cash assistance to state relief agencies struggling to care for the unemployed; ((Neil Maher, Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).)) the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) built a series of hydroelectric dams along the Tennessee River as part of a comprehensive program to economically develop a chronically depressed region; ((Thomas K. McCraw, TVA and the Power Fight, 1933-1939 (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1971).)) several agencies helped home and farm owners refinance their mortgages. And Roosevelt wasn’t done.

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 The heart of Roosevelt’s early recovery program consisted of two massive efforts to stabilize and coordinate the American economy: the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) and the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The AAA, created in May 1933, aimed to raise the prices of agricultural commodities (and hence farmers’ income) by offering cash incentives to voluntarily limit farm production (decreasing supply, thereby raising prices). ((Ellis W. Hawley, The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly: A Study in Economic Ambivalence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969); Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1986), 217.)) The National Industrial Recovery Act, which created the National Recovery Administration (NRA) in June 1933, suspended antitrust laws to allow businesses to establish “codes” that would coordinate prices, regulate production levels, and establish conditions of employment to curtail “cutthroat competition.” In exchange for these exemptions, businesses agreed to provide reasonable wages and hours, end child labor, and allow workers the right to unionize. Participating businesses earned the right to display a placard with the NRA’s “Blue Eagle,” showing their cooperation in the effort to combat the Great Depression. ((Theodore Saloutos, The American Farmer and the New Deal (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1982).))

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 The programs of the First Hundred Days stabilized the American economy and ushered in a robust though imperfect recovery. GDP climbed once more, but even as output increased, unemployment remained stubbornly high. Though the unemployment rate dipped from its high in 1933, when Roosevelt was inaugurated, vast numbers remained out of work. If the economy could not put people back to work, the New Deal would try. The Civil Works Administration (CWA) and, later, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) put unemployed men and women to work on projects designed and proposed by local governments. The Public Works Administration (PWA) provided grants-in-aid to local governments for large infrastructure projects, such as bridges, tunnels, schoolhouses, libraries, and America’s first federal public housing projects. Together, they provided not only tangible projects of immense public good, but employment for millions. The New Deal was reshaping much of the nation. ((Bonnie Fox Schwartz, The Civil Works Administration, 1933–1934: The Business of Emergency Employment in the New Deal (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984); Edwin Amenta, Bold Relief: Institutional Politics and the Origins of Modern American Social Policy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998); Jason Scott Smith, Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933–1956 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Mason B. Williams, City of Ambition: FDR, La Guardia, and the Making of Modern New York (New York: Norton, 2013).))

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0

VIII. The New Deal in the South

¶ 54

Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0

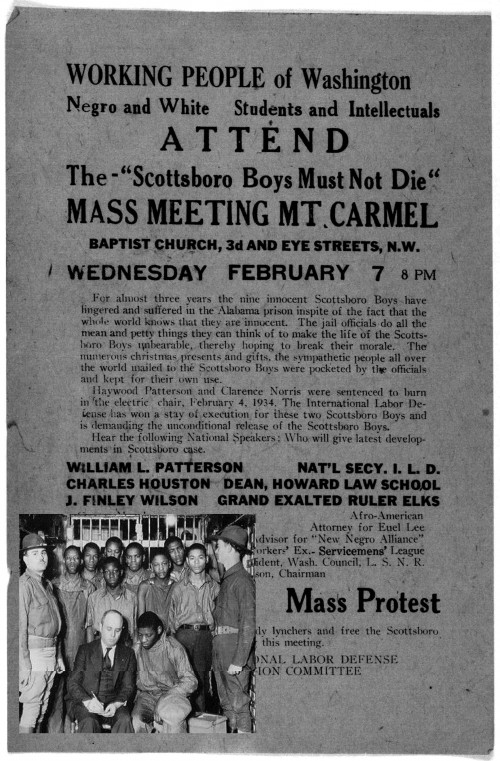

The accusation of rape brought against the so-called Scottsboro Boys, pictured with their attorney in 1932, generated controversy across the country. “The Scottsboro Boys, with attorney Samuel Leibowitz, under guard by the state militia, 1932.” Wikipedia.

The accusation of rape brought against the so-called Scottsboro Boys, pictured with their attorney in 1932, generated controversy across the country. “The Scottsboro Boys, with attorney Samuel Leibowitz, under guard by the state militia, 1932.” Wikipedia.

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 The impact of initial New Deal legislation was readily apparent in the South, a region of perpetual poverty especially plagued by the Depression. In 1929 the average per capita income in the American Southeast was $365, the lowest in the nation. Southern farmers averaged $183 per year at a time when farmers on the West Coast made more than four times that. ((Howard Odum, Southern Regions of the United States (1936), quoted in David L. Carlton and Peter Coclanis, eds., Confronting Southern Poverty in the Great Depression: The Report on Economic Conditions of the South with Related Documents (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1996): 118-19.)) Moreover, they were trapped into the production of cotton and corn, crops that depleted the soil and returned ever-diminishing profits. Despite the ceaseless efforts of civic boosters, what little industry the South had remained low-wage, low-skilled, and primarily extractive. Southern workers made significantly less than their national counterparts: 75% of non-southern textile workers, 60% of iron and steel workers, and a paltry 45% of lumber workers. At the time of the crash, southerners were already underpaid, underfed, and undereducated. ((Gavin Wright, Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1986), 217.))

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 Major New Deal programs were designed with the South in mind. FDR hoped that by drastically decreasing the amount of land devoted to cotton, the AAA would arrest its long-plummeting price decline. Farmers plowed up existing crops and left fields fallow, and the market price did rise. But in an agricultural world of land-owners and landless farmworkers (such as tenants and sharecroppers), the benefits of the AAA bypassed the southerners who needed them most. The government relied on land owners and local organizations to distribute money fairly to those most affected by production limits, but many owners simply kicked tenants and croppers off their land, kept the subsidy checks for keeping those acres fallow, and reinvested the profits in mechanical farming equipment that further suppressed the demand for labor. Instead of making farming profitable again, the AAA pushed landless southern farmworkers off the land. ((Ibid., 227-228.))

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 But Roosevelt’s assault on southern poverty took many forms. Southern industrial practices attracted much attention. The NRA encouraged higher wages and better conditions. It began to suppress the rampant use of child labor in southern mills, and, for the first time, provided federal protection for unionized workers all across the country. Those gains were eventually solidified in the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, which set a national minimum wage of $0.25/hour (eventually rising to .40/hour). The minimum wage disproportionately affected low-paid southern workers, and brought southern wages within the reach of northern wages. ((Ibid., 216-220.))

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 The president’s support for unionization further impacted the South. Southern industrialists had proven themselves ardent foes of unionization, particularly in the infamous southern textile mills. In 1934, when workers at textile mills across the southern Piedmont struck over low wages and long hours, owners turned to local and state authorities to quash workers’ groups, even as they recruited thousands of strikebreakers from the many displaced farmers swelling industrial centers looking for work. But in 1935 the National Labor Relations Act, also known as the Wagner Act, guaranteed the rights of most workers to unionize and bargain collectively. And so unionized workers, backed by the support of the federal government and determined to enforce the reforms of the New Deal, pushed for higher wages, shorter hours, and better conditions. With growing success, union members came to see Roosevelt as a protector or workers’ rights. Or, as one union leader put it, an “agent of God.” ((William Leuchtenberg, The White House Looks South: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Lyndon B. Johnson (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2005), 74.))

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0 Perhaps the most successful New Deal program in the South was the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), an ambitious program to use hydroelectric power, agricultural and industrial reform, flood control, economic development, education, and healthcare, to radically remake the impoverished watershed region of the Tennessee River. Though the area of focus was limited, Roosevelt’s TVA sought to “make a different type of citizen” out of the area’s penniless residents. ((“Press Conference #160,” 23 November 1934, 214, in Roosevelt, Complete Presidential Press Conferences of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Volumes 3-4, 1934 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972).)) The TVA built a series of hydroelectric dams to control flooding and distribute electricity to the otherwise non-electrified areas at government-subsidized rates. Agents of the TVA met with residents and offered training and general education classes to improve agricultural practices and exploit new job opportunities. The TVA encapsulates Roosevelt’s vision for uplifting the South and integrating it into the larger national economy. ((Thomas K. McCraw, TVA and the Power Fight, 1933-1939 (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1971).))

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 1 Roosevelt initially courted conservative southern Democrats to ensure the legislative success of the New Deal, all but guaranteeing that the racial and economic inequalities of the region remained intact, but, by the end of his second term, he had won the support of enough non-southern voters that he felt confident in confronting some of the region’s most glaring inequalities. Nowhere was this more apparent than in his endorsement of a report, formulated by a group of progressive southern New Dealers, entitled “A Report on Economic Conditions in the South.” The pamphlet denounced the hardships wrought by the southern economy—in his introductory letter to the Report, called the region “the Nation’s No. 1 economic problem”—and blasted reactionary southern anti-New Dealers. He suggested that the New Deal could save the South and thereby spur a nationwide recovery. The Report was among the first broadsides in Roosevelt’s coming reelection campaign that addressed the inequalities that continued to mark southern and national life. ((Carleton and Coclanis, eds., Confronting Southern Poverty in the Great Depression, 42.))

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0

IX. The New Deal in Appalachia

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0 The New Deal also addressed another poverty-stricken region, Appalachia, the mountain-and-valley communities that roughly follow the Appalachian Mountain Range from southern New York to the foothills of Northern Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Appalachia’s abundant natural resources, including timber and coal, were in high demand during the country’s post-Civil War industrial expansion, but Appalachian industry simply extracted these resources for profit in far-off industries, depressing the coal-producing areas even earlier than the rest of the country. By the mid-1930s, with the Depression suppressing demand, many residents were stranded in small, isolated communities whose few employers stood on the verge of collapse. Relief workers from the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) reported serious shortages of medical care, adequate shelter, clothing, and food. Rampant illnesses, including typhus, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and venereal disease, as well as childhood malnutrition, further crippled Appalachia.

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 Several New Deal programs targeted the region. Under the auspices of the NIRA, Roosevelt established the Division of Subsistence Homesteads (DSH) within the Department of the Interior to give impoverished families an opportunity to relocate “back to the land”: the DSH established 34 homestead communities nationwide, including the Appalachian regions of Alabama, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and West Virginia. The CCC contributed to projects throughout Appalachia, including the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina and Virginia, reforestation of the Chattahoochee National Forest in Georgia, and state parks such as Pine Mountain Resort State Park in Kentucky. The TVA’s efforts aided communities in Tennessee and North Carolina, and the Rural Electric Administration (REA) brought electricity to 288,000 rural households.

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0

X. Voices of Protest

¶ 65

Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0

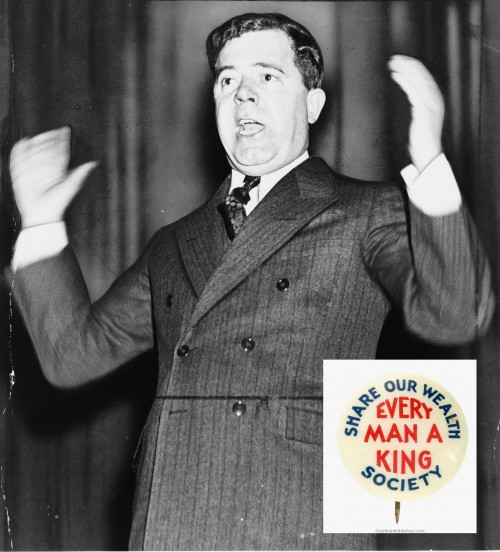

Huey Long was a dynamic, indomitable force (with a wild speech-giving style, seen in the photograph) who campaigned tirelessly for the common man, demanding that Americans “Share Our Wealth.” Photograph of Huey P. Long, c. 1933-35. Wikimedia.

Huey Long was a dynamic, indomitable force (with a wild speech-giving style, seen in the photograph) who campaigned tirelessly for the common man, demanding that Americans “Share Our Wealth.” Photograph of Huey P. Long, c. 1933-35. Wikimedia.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0 Despite the unprecedented actions taken in his first year in office, Roosevelt’s initial relief programs could often be quite conservative. He had usually been careful to work within the bounds of presidential authority and congressional cooperation. And, unlike Europe, where several nations had turned towards state-run economies, and even fascism and socialism, Roosevelt’s New Deal demonstrated a clear reluctance to radically tinker with the nation’s foundational economic and social structures. Many high-profile critics attacked Roosevelt for not going far enough, and, beginning in 1934, Roosevelt and his advisors were forced to respond.

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0 Senator Huey Long, a flamboyant Democrat from Louisiana, was perhaps the most important “voice of protest.” Long’s populist rhetoric appealed those who saw deeply rooted but easily addressed injustice in the nation’s economic system. Long proposed a “Share Our Wealth” program in which the federal government would confiscate the assets of the extremely wealthy and redistribute them to the less well-off through guaranteed minimum incomes. “How many men ever went to a barbecue and would let one man take off the table what’s intended for nine-tenths of the people to eat?” he asked. Over 27,000 “Share the Wealth” clubs sprang up across the nation as Long traveled the country explaining his program to crowds of impoverished and unemployed Americans. Long envisioned the movement as a stepping stone to the presidency, but his crusade ended in late 1935 when he was assassinated on the floor of the Louisiana state capitol. Even in death, however, Long convinced Roosevelt to more stridently attack the Depression and American inequality.

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0 But Huey Long was not alone in his critique of Roosevelt. Francis Townsend, a former doctor and public health official from California, promoted a plan for old age pensions which, he argued, would provide economic security for the elderly (who disproportionately suffered poverty) and encourage recovery by allowing older workers to retire from the work force. Reverend Charles Coughlin, meanwhile, a priest and radio personality from the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, gained a following by making vitriolic, anti-Semitic attacks on Roosevelt for cooperating with banks and financiers and proposing a new system of “social justice” through a more state-driven economy instead. Like Long, both Townsend and Coughlin built substantial public followings.

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 1 If many Americans urged Roosevelt to go further in addressing the economic crisis, the president faced even greater opposition from conservative politicians and business leaders. By late 1934, growing complaints from business-friendly Republicans of Roosevelt’s willingness to regulate industry and use federal spending for public works and employment programs. In the South, Democrats who had originally supported the president grew increasingly hostile towards programs that challenged the region’s political, economic, and social status quo. Yet the greatest opposition came from the Supreme Court, a conservative filled with appointments made from the long years of Republican presidents.

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0 By early 1935 the Court was reviewing programs of the New Deal. On May 27, a day Roosevelt’s supporters called “Black Monday,” the justices struck down one of the president’s signature reforms: in a case revolving around poultry processing, the Court unanimously declared the NRA unconstitutional. In early 1936, the AAA fell. ((William E. Leuchtenburg, The Supreme Court Reborn: The Constitutional Revolution in the Age of Roosevelt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); Theda Skocpol and Kenneth Finegold, State and Party in America’s New Deal (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995); Colin Gordon, New Deals: Business, Labor, and Politics in America, 1920–1935 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994).))

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0

XI. The “Second” New Deal (1935-1936)

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0 Facing reelection and rising opposition from both the left and the right, Roosevelt decided to act. The New Deal adopted a more radical, aggressive approach to poverty, the “Second” New Deal. In 1935, hoping to reconstitute some of the protections afforded workers in the now-defunct NRA, Roosevelt worked with Congress to pass the National Labor Relations Act (known as the Wagner Act for its chief sponsor, New York Senator Robert Wagner), offering federal legal protection, for the first time, for workers to organize unions. Three years later, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, creating the modern minimum wage. The Second New Deal also oversaw the restoration of a highly progressive federal income tax, mandated new reporting requirements for publicly traded companies, refinanced long-term home mortgages for struggling homeowners, and attempted rural reconstruction projects to bring farm incomes in line with urban ones. (( Mark H. Leff, The Limits of Symbolic Reform: The New Deal and Taxation, 1933–1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984); Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); Sarah T. Phillips, This Land, This Nation: Conservation, Rural America, and the New Deal (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).))

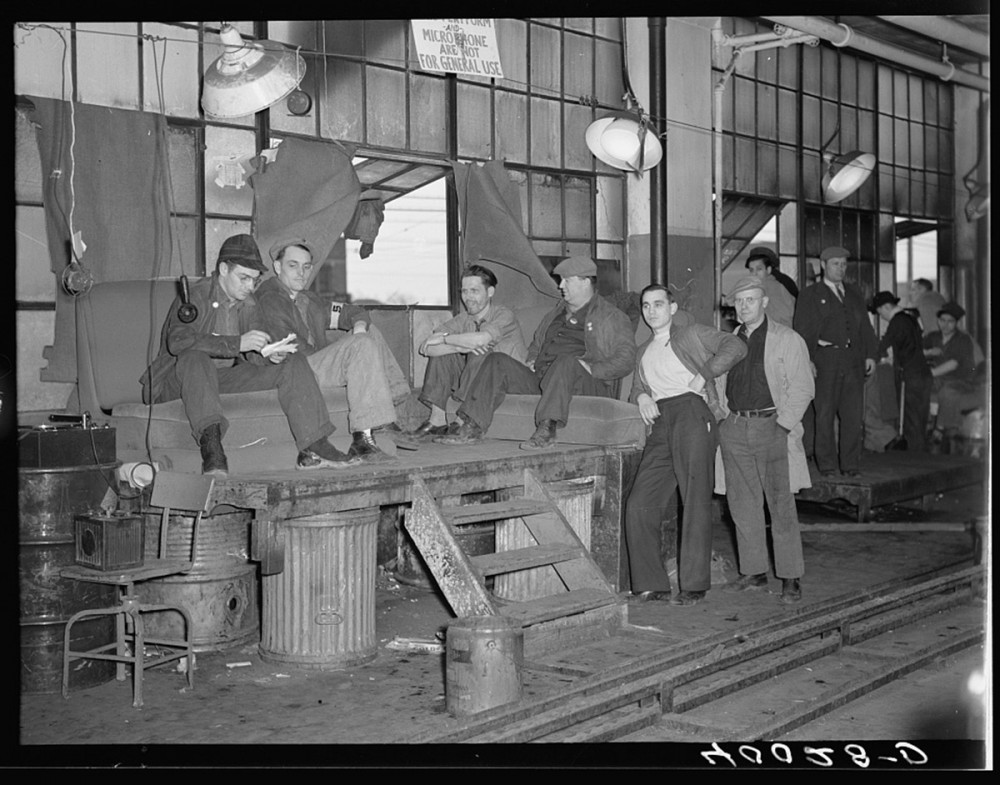

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 The labor protections extended by Roosevelt’s New Deal were revolutionary. In northern industrial cities, workers responded to worsening conditions by banding together and demanding support for worker’s rights. In 1935, the head of the United Mine Workers, John L. Lewis, took the lead in forming a new national workers’ organization, the Congress of Industrial Organizations, breaking with the more conservative, craft-oriented AFL. The CIO won a major victory in 1937 when affiliated members in the United Auto Workers struck for recognition and better pay and hours at a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan. In the first instance of a “sit-down” strike, the workers remained in the building until management agreed to negotiate. GM recognized the UAW and the “sit-down” strike became a new weapon in the fight for workers’ rights. Across the country, unions and workers took advantage of the New Deal’s protections to organize and win major concessions from employers.

¶ 74

Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0

Unionization met with fierce opposition from owners and managers, particularly in the “Manufacturing Belt” of the Mid-West. Sheldon Dick, photographer, “Strikers guarding window entrance to Fisher body plant number three. Flint, Michigan,” January/February 1937. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa2000021503/PP/.

Unionization met with fierce opposition from owners and managers, particularly in the “Manufacturing Belt” of the Mid-West. Sheldon Dick, photographer, “Strikers guarding window entrance to Fisher body plant number three. Flint, Michigan,” January/February 1937. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa2000021503/PP/.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0 The signature piece of Roosevelt’s Second New Deal came the same year, in 1935. The Social Security Act provided for old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, and economic aid, based on means, to assist both the elderly and dependent children. The president was careful to mitigate some of the criticism from what was, at the time, in the American context, a revolutionary concept. He specifically insisted that social security be financed from payroll, not the federal government; “No dole,” Roosevelt said repeatedly, “mustn’t have a dole.” ((Kennedy, 267.)) He thereby helped separate Social Security from the stigma of being an undeserved “welfare” entitlement. While such a strategy saved the program from suspicions, Social Security became the centerpiece of the modern American social welfare state. It was the culmination of a long progressive push for government-sponsored social welfare, an answer to the calls of Roosevelt’s opponents on the Left for reform, a response to the intractable poverty among America’s neediest groups, and a recognition that the government would now assume some responsibility for the economic well-being of its citizens. But for all of its groundbreaking provisions, the Act, and the larger New Deal as well, excluded large swaths of the American population. ((W. Andrew Achenbaum, Old Age in the New Land (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978); Edwin E. Witte, The Development of the Social Security Act (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1963).))

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0

XII. Equal Rights and the New Deal

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 1 The Great Depression was particularly tough for nonwhite Americans. As an African American pensioner told interviewer Studs Terkel, “The Negro was born in depression. It didn’t mean too much to him. The Great American Depression … only became official when it hit the white man.” Black workers were generally the last hired when businesses expanded production and the first fired when businesses experienced downturns. In 1932, with the national unemployment average hovering around 25%, black unemployment reached as high as 50%, while even those black who kept their jobs saw their already low wages cut dramatically. ((Terkel, Hard Times, 82.))

¶ 78 Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0 Blacks faced discrimination everywhere, but suffered especially severe legal inequality in the Jim Crow South. In 1931, for instance, a group of nine young men riding the rails between Chattanooga and Memphis, Tennessee, were pulled from the train near Scottsboro, Alabama, and charged with assaulting two white women. Despite clear evidence that the assault had not occurred, and despite one of the women later recanting, the young men endured a series of sham trials in which all but one were sentenced to death. Only the communist-oriented International Legal Defense came to the aid of the “Scottsboro Boys,” who soon became a national symbol of continuing racial prejudice in America and a rallying point for civil rights-minded Americans. In appeals, the ILD successfully challenged the Boys’ sentencing and the death sentences were either commuted or reversed, although the last of the accused did not receive parole until 1946. ((Dan T/. Carter, Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969).))

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0 Despite a concerted effort to appoint black advisors to some New Deal programs, Franklin Roosevelt did little to directly address the difficulties black communities faced. To do so openly would provoke southern Democrats and put his New Deal coalition–the uneasy alliance of national liberals, urban laborers, farm workers, and southern whites–at risk. Roosevelt not only rejected such proposals as abolishing the poll tax and declaring lynching a federal crime, he refused to specifically target African American needs in any of his larger relief and reform packages. As he explained to the national secretary of the NAACP, “I just can’t take that risk.” ((Kennedy, 201.))

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 1 In fact, even many of the programs of the New Deal had made hard times more difficult. When the codes of the NRA set new pay scales, they usually took into account regional differentiation and historical data. In the South, where African Americans had long suffered unequal pay, the new codes simply perpetuated that inequality. The codes also exempted those involved in farm work and domestic labor, the occupations of a majority of southern black men and women. The AAA was equally problematic as owners displaced black tenants and sharecroppers, many of whom were forced to return to their farms as low-paid day labor or to migrate to cities looking for wage work. ((Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Norton, 2005).))

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0 Perhaps the most notorious failure of the New Deal to aid African Americans came with the passage of the Social Security Act. Southern politicians chaffed at the prospect of African Americans benefiting from federally-sponsored social welfare, afraid that economic security would allow black southerners to escape the cycle of poverty that kept them tied to the land as cheap, exploitable farm laborers. The Jackson (Mississippi) Daily News callously warned that “The average Mississippian can’t imagine himself chipping in to pay pensions for able-bodied Negroes to sit around in idleness … while cotton and corn crops are crying for workers.” Roosevelt agreed to remove domestic workers and farm laborers from the provisions of the bill, excluding many African Americans, already laboring under the strictures of legal racial discrimination, from the benefits of an expanding economic safety net. ((George Brown Tindall, The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945 (Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1967). 491.))

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0 Women, too, failed to receive the full benefits of New Deal programs. On one hand, Roosevelt included women in key positions within his administration, including the first female Cabinet secretary, Frances Perkins, and a prominently placed African American advisor in the National Youth Administration, Mary McLeod Bethune. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a key advisor to the president and became a major voice for economic and racial justice. But many New Deal programs were built upon the assumption that men would serve as “breadwinners” and women as mothers, homemakers, and consumers. New Deal programs aimed to help both but usually by forcing such gendered assumptions, making it difficult for women to attain economic autonomy. New Deal social welfare programs tended to funnel women into means-tested, state administered relief programs while reserving “entitlement” benefits for male workers, creating a kind of two-tiered social welfare state. And so, despite great advances, the New Deal failed to challenge core inequalities that continued to mark life in the United States. ((Alice Kessler-Harris, In Pursuit of Equity: Women, Men, and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in 20th Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001); Linda Gordon, Pitied But Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare, 1890–1935 (New York: Free Press, 1994);))

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0

XIII. The End of the New Deal (1937-1939)

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0 By 1936 Roosevelt and his New Deal had won record popularity. In November Roosevelt annihilated his Republican challenger, Governor Alf Landon of Kansas, who lost in every state save Maine and Vermont. The Great Depression had certainly not ended, but it appeared to many to be beating a slow yet steady retreat, and Roosevelt, now safely re-elected, appeared ready to take advantage of both his popularity and the improving economic climate to press for even more dramatic changes. But conservative barriers continued to limit the power of his popular support. The Supreme Court, for instance, continued to gut many of his programs.

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0 In 1937, concerned that the Court might overthrow Social Security in an upcoming case, Roosevelt called for legislation allowing him to expand the Court by appointing a new, younger justice for every sitting member over the age of 70. Roosevelt argued that the measure would speed up the Court’s ability to handle a growing back-log of cases; however, his “court-packing scheme,” as opponents termed it, was clearly designed to allow the president to appoint up to six friendly, pro-New Deal justices to drown the influence of old-time conservatives on the Court. Roosevelt’s “scheme” riled opposition and did not become law, but the chastened Court upheld Social Security and other pieces of New Deal legislation thereafter. Moreover, Roosevelt was slowly able to appoint more amenable justices as conservatives died or retired. Still, the “court-packing scheme” damaged the Roosevelt administration and opposition to the New Deal began to emerge and coalesce. ((Alan Brinkley, The End of Reform: New Deal Liberalism in Recession and War (New York: Knopf, 1995).))

¶ 86 Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0 Compounding his problems, Roosevelt and his advisors made a costly economic misstep. Believing the United States had turned a corner, Roosevelt cut spending in 1937. The American economy plunged nearly to the depths of 1932–1933. Roosevelt reversed course and, adopting the approach popularized by the English economist John Maynard Keynes, hoped that countercyclical, “compensatory” spending would pull the country out of the recession, even at the expense of a growing budget deficit. It was perhaps too late. The “Roosevelt Recession” of 1937 became fodder for critics. Combined with the “court-packing scheme,” the recession allowed for significant gains by a “conservative coalition” of southern Democrats and Midwestern Republicans. By 1939, Roosevelt struggled to build congressional support for new reforms, let alone maintain existing agencies. Moreover, the growing threat of war in Europe stole the public’s attention and increasingly dominated Roosevelt’s interests. The New Deal slowly receded into the background, outshone by war. ((Ibid.))

¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0

XIV. The Legacy of the New Deal

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0 By the end of the 1930s, Roosevelt and his Democratic congresses had presided over a transformation of the American government and a realignment in American party politics. Before World War I, the American national state, though powerful, had been a “government out of sight.” After the New Deal, Americans came to see the federal government as a potential ally in their daily struggles, whether finding work, securing a decent wage, getting a fair price for agricultural products, or organizing a union. Voter turnout in presidential elections jumped in 1932 and again in 1936, with most of these newly-mobilized voters forming a durable piece of the Democratic Party that would remain loyal well into the 1960s. Even as affluence returned with the American intervention in World War II, memories of the Depression continued to shape the outlook of two generations of Americans. ((Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990); Kristi Andersen, The Creation of a Democratic Majority, 1928–1936 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979); Caroline Bird, The Invisible Scar (New York: D. McKay Co., 1966).)) Survivors of the Great Depression, one man would recall in the late 1960s, “are still riding with the ghost—the ghost of those days when things came hard.” ((Quoted in Studs Terkel, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (New York: Pantheon, 1970), 34.))

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0 Historians debate when the New Deal “ended.” Some identify the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 as the last major New Deal measure. Others see wartime measures such as price and rent control and the G.I. Bill (which afforded New Deal-style social benefits to veterans) as species of New Deal legislation. Still others conceive of a “New Deal order,” a constellation of “ideas, public policies, and political alliances,” which, though changing, guided American politics from Roosevelt’s Hundred Days forward to Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society—and perhaps even beyond. Indeed, the New Deal’s legacy still remains, and its battle lines still shape American politics.

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 0

XV. Reference Material

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0 This chapter was edited by Matthew Downs, with content contributed by Dana Cochran, Matthew Downs, Benjamin Helwege, Elisa Minoff, Caitlin Verboon, and Mason Williams.

¶ 92 Leave a comment on paragraph 92 0 Recommended citation: Dana Cochran et al., “The Great Depression,” Matthew Downs, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2016, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

¶ 93 Leave a comment on paragraph 93 0

¶ 94 Leave a comment on paragraph 94 0 Recommended Reading

- ¶ 95 Leave a comment on paragraph 95 0

- Balderrama, Francisco E., and Rodríguez, Raymond. Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (Revised Edition). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

- Brinkley, Alan, The End of Reform: New Deal Liberalism in Recession and War. New York: Knopf, 1995.

- Brinkley, Alan. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression. New York: Knopf, 1982.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919–1939. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Cowie, Jefferson, and Salvatore, Nick. “The Long Exception: Rethinking the Place of the New Deal in American History,” International Labor and Working-Class History 74 (Fall 2008): 1-32.

- Dickstein, Morris. Dancing in the Dark a Cultural History of the Great Depression. Norton, 2009.

- The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930–1980. Edited by Fraser, Steve, and Gerstle, Gary. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Gilmore, Glenda E. Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950. New York: Norton, 2009.

- Gordon, Colin. New Deals: Business, Labor, and Politics in America 1920-1935. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Gordon, Linda. Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits. New York: Norton, 2009.

- Gordon, Linda. Pitied But Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare 1890-1935. New York: The Free Press, 1994.

- Greene, Alison Collis. No Depression in Heaven: The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015

- Katznelson, Ira. Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time. New York: Norton, 2013.

- Kelly, Robin D. G. Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

- Kennedy, David. Freedom From Fear: America in Depression and War, 1929-1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Kessler-Harris, Alice. In Pursuit of Equity: Women, Men, and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in 20th-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Leach, William. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture. New York: Pantheon, 1993.

- Leuchtenburg, William. Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

- Pells, Richard. Radical Visions and American Dreams: Culture and Social Thought in the Depression Years. New York: Harper & Row, 1973.

- Phillips, Kimberly L. Alabama North: African-American Migrants, Community and Working-Class Activism in Cleveland, 1915-1945. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

- Phillips-Fein, Kim. Invisible Hands: The Businessmen’s Crusade Against the New Deal. New York: Norton, 2010

- Sitkoff, Harvard. A New Deal for Blacks: the Emergence of Civil Rights as a National Issue. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- Sullivan, Patricia. Days of Hope: Race and Democracy in the New Deal Era. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- Tani, Karen. States of Dependency: Welfare, Rights, and American Governance, 1935–1972. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Wright, Gavin. Old South, New South: Revolutions in the Southern Economy since the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986.

¶ 96 Leave a comment on paragraph 96 0

¶ 97 Leave a comment on paragraph 97 0 Notes

[Panicked selling set in]

*Panic

[ stock sunk]

*stocks

Maybe better?

Will be fixed. Thanks!

[of the J.D. Rockefeller’s]

*of J.D. Rockefeller’s

Will be fixed. Thanks!